Berta Cáceres’ killing was a symptom, not an isolated incident. In memory of Nelson García.

by Andrea Reyes Blanco and Tim Shenk

This article appeared first on teleSUR, here.

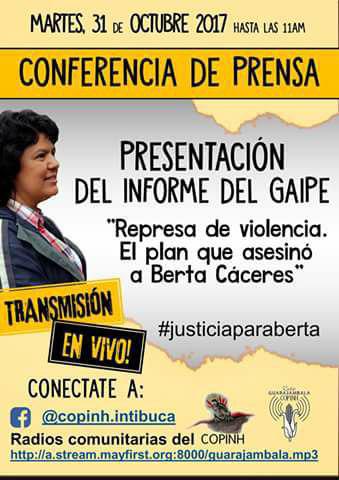

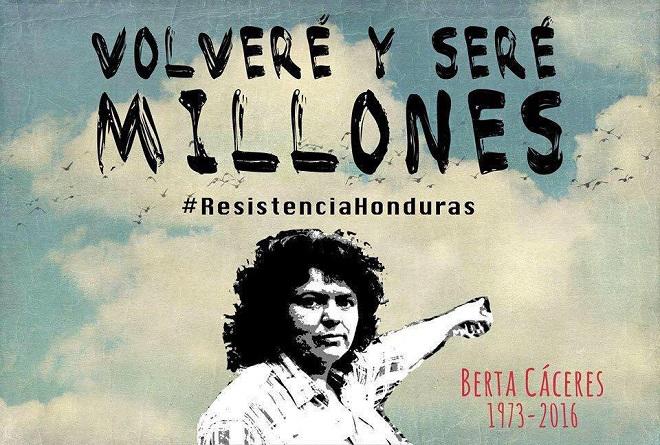

Berta Cáceres wasn’t the first and, unfortunately, she hasn’t been the last. The world-renowned Lenca leader assassinated last month in Honduras for her opposition to government-backed megaprojects is one of an increasing litany of fallen fighters for indigenous and environmental rights in Honduras and around the globe.

The pattern of murder and criminalization of those who would defend land and the rights of rural people has only gotten more clear. We argue that this pattern responds to the land grab phenomenon that has intensified since the global financial and food crisis of 2007-2008.

On March 15 another Honduran environmental and indigenous activist was murdered. Nelson García was an active member of the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (Copinh). His murder took place “when he came home for lunch, after having spent the morning helping to move the belongings of evicted families from the Lenca indigenous community of Rio Chiquito,” said Copinh.

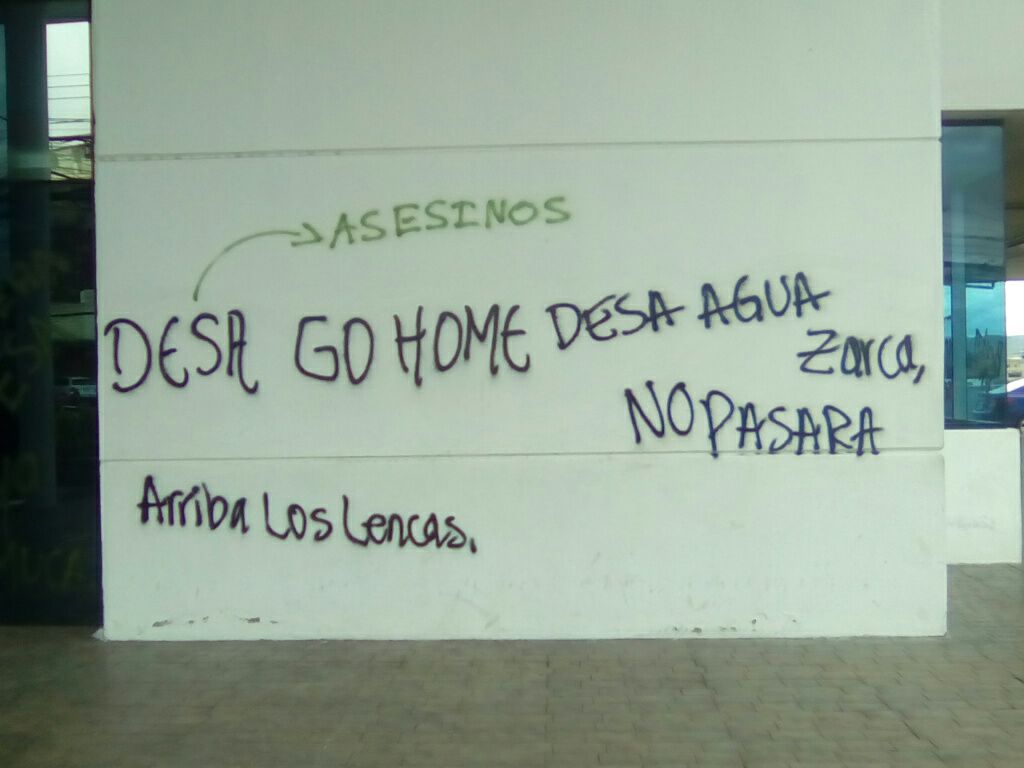

García was a colleague of the recently slain Cáceres, working with communities opposing the Agua Zarca hydroelectric dam project. The Agua Zarca dam project, which has recently begun to lose funding, would provide energy for the numerous extractive projects slated for Honduras in the coming decade. Since the 2009 coup d’etat against President Manuel Zelaya, 30 percent of Honduran territory has been allocated to mining concessions.

The eviction after which García was killed was one of many recent violent evictions carried out by Honduran military police in indigenous territories. Elevated levels of state violence and disregard for due process are business as usual nowadays in Honduras, according to civil society organizations.

In its February 21 report on the Situation of Human Rights in Honduras, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) expressed concern about the high levels of violence and insecurity present in Honduran society, highlighting risks to indigenous people. The report pointed out that violence against indigenous people has emerged to a large degree from land grabs. The violence is exacerbated by a context of inequality and discrimination, in addition to the consequent barriers to access to justice. Official figures released in April 2013 by then Attorney General Luis Alberto Rubí indicate that 80 percent of killings in Honduras went unpunished due to a lack of capacity on the part of investigative bodies.

According to the IACHR report, the challenges that indigenous communities face are mainly related to: “(i) the high levels of insecurity and violence arising from the imposition of project and investment plans and natural resource mining concessions on their ancestral territories; (ii) forced evictions through the excessive use of force and (iii) the persecution and criminalization of indigenous leaders for reasons related to the defense of their ancestral territories.”

Moreover, the IACHR has clearly stated that many of the attacks carried out against indigenous leaders and advocates are specifically aimed at reducing their activities in defense and protection of their territories and natural resources, as well as the defense of the right to autonomy and cultural identity.

Harassment takes the form not only of targeted criminal attacks, as we have seen in the case of Berta Cáceres, Nelson García and many others, but a much broader net has been cast against environmental and indigenous leaders. Official state entities, enacting formal legal procedures, have used the judicial system to catch activists in false charges, resulting in months or years of preventive prison, bogus sentences, legal fees and often a permanent criminal record. In a context in which state violence intertwines itself with the violence of international economic power, corruption and unethical practices, hundreds of leaders have been prosecuted for crimes such as usurpation of land and damage to the environment.

What we see in Honduras is part of the global land grab phenomenon, a term that in the words of Phillip McMichael, professor of development sociology at Cornell University, “invokes a long history of violent enclosure of common lands to accommodate world capitalist expansion, but it sits uneasily with the ‘free market’ rhetoric of neoliberal ideology.” Land grabs are a symptom of a crisis of accumulation in the neoliberal globalization project, which has intensified since the global financial and food crisis of 2007-2008. This in turn is linked to an acceleration of a restructuring process of the food regime as a consequence of a large-scale relocation of agro-industry to the global south.

According to the 2011 Oxfam briefing paper, “Land and Power, the growing scandal surrounding the new wave of investment in land,” recent records of investment show a rapidly increasing pressure on land, resulting in dispossession, deception, violation of human rights and destruction of livelihoods. It is a war on indigenous peoples conducted in order to establish modern corporate capitalism.

Indeed, all around the world peasants and indigenous people are being displaced from their territories in order to develop large-scale agribusiness, such as massive palm oil and soy plantations, mining projects, hydroelectric dams and tourist resorts, among other investments. State-sanctioned violence and impunity create the conditions for investors to acquire land that would otherwise not be for sale. The result is a serious threat to the subsistence and socio-ecological resilience of millions of people across the world.

One of the most dramatic examples of this process is the case of the Honduran Palm Oil Company Grupo Dinant, which has an extended record of violence and human rights abuses associated with the killing of more than 100 peasants in Lower Aguan Valley. The Unified Peasants Movement of the Aguán Valley (MUCA) waged a long battle to defend their land rights, sustaining many losses. In addition, international human rights groups such as FoodFirst Information and Action Network (FIAN) brought pressure to bear, and in 2011 the Honduran government was forced to convene MUCA and the company to negotiate a deal. Paradoxically, according to the deal, the farmers have to buy back the disputed land at market prices (Oxfam 2011).

Land grabbing in Honduras has a long and lamentable history, and related violence has increased dramatically since the 2009 coup d’etat. Despite regular violent evictions by state security forces, indigenous and peasant groups continue to pursue their right to control their ancestral lands through land occupations.

Those who are incensed by the killing of Berta Cáceres must understand that her assassination was not an isolated event carried out by those who had a personal vendetta against her. Rather, Berta, her colleagues at Copinh and other indigenous organizations represent an obstacle for those who would further a vision of society that values profit over all else.

Andrea Reyes Blanco is a Humphrey Fellow at Cornell University, and Tim Shenk is Coordinator of the Cornell-based Committee on U.S.-Latin American Relations (CUSLAR).