Sorry, this entry is only available in Español. For the sake of viewer convenience, the content is shown below in the alternative language. You may click the link to switch the active language.

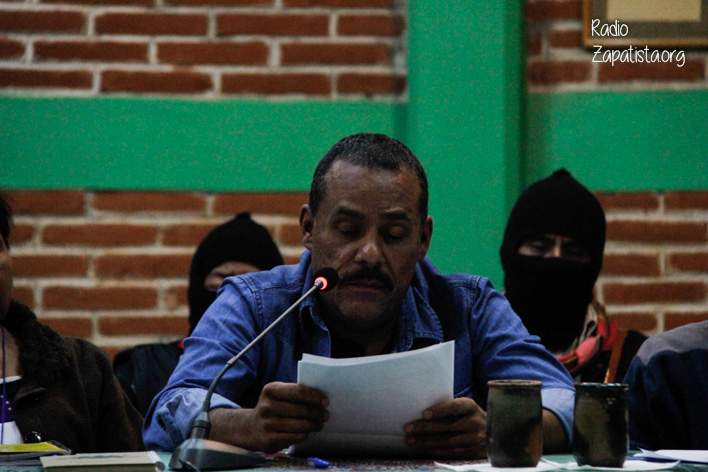

San Cristóbal, Chiapas. 13 de abril. “Los migrantes no se fueron por que quisieron, sino porque ya no pudieron estar en su finca, mejor conocida como país”, expuso esta noche el subcomandante Moisés, al reiterar su apoyo a los que han emigrado a los Estados Unidos, debido a la pobreza y violencia en su lugar de origen; donde los explotan, reprimen y despojan como en una finca de hace 100 años. Dichas declaraciones las expresó el insurgente chiapaneco en el segundo día del seminario “Los muros del capital, las grietas de la izquierda”, en el Cideci Unitierra, Chiapas.

“Hay que apoyar a quienes nos apoyaron. Nos toca ahora decirles que luchen con resistencia y rebeldía”, es como explicó Moisés, el por qué se solidarizan con la sociedad discriminada y explotada. Ell@s nos ayudaron hace 23 años después de nuestro levantamiento, abundó el vocero zapatista e informó que apoyarán a las y los migrantes en la unión americana con los ingresos de la venta de 3791 kilos de café.

El indígena zapatista convocó nuevamente a la sociedad a organizarse por que “el enemigo capitalista no va dejar que el pueblo mande”. “El enemigo no va a negociar y decir, te voy a medio explotar”, puntualizó el subcomandante. “Necesitamos ayudarnos entre los de abajo, para demostrar que no necesitamos a los que dan apoyo condicionado”, agregó Moisés, en referencia al gobierno y partidos políticos. “hay que reorganizarnos, reeducar lo que ya creíamos que estaba educado”, convocó.

Por su parte el historiador Carlos Aguirre Rojas, con su ponencia “situación de América latina, vista desde abajo y a la izquierda”, invitó a aprender lo que los zapatistas han enseñado, que es a mirar el mundo desde abajo y a la izquierda. “No podemos entender el capitalismo del siglo XXI, sin apoyarnos en la teoría del valor y de la historia de Marx”, también agregó el académico.

¿Cómo podemos ver el arriba de la América latina?, inició preguntando el investigador social, a lo que respondió que existen dos elementos. El primero son los Estados: los cuales pueden ser de ultra derecha, como el de Peña Nieto, que son antinacionales, entreguistas, represores y anticulturales; o pueden ser Estados denominados “progresistas”, como en Venezuela, Bolivia o Ecuador, que en un inicio no apuestan a la represión sino a la cooptación, y que a pesar de su discurso son profundamente pro-capitalistas, como en el caso de López Obrador, expuso.

Otra de los cuestionamientos hechos por Aguirre Rojas fue ¿cómo se presenta el cuadro de los de arriba?, respondiendo con la analogía hecha por el subcomandante Moisés, el día de ayer, en la que los países han pasado a ser como fincas a cargo de la burguesía internacional, la cual no le interesa su merca do interno y son antinacionalistas, citando el caso de Carlos Slim en México. “El Estado es parte del arriba, siempre será el enemigo”, evidenció el historiador, por lo que recomendó que en su lugar se ponga un gobierno como el de los zapatistas, que mande obedeciendo.

En la sesión de esta noche también estuvo el sociólogo Arturo Anguiano, quien destacó el carácter reivindicativo de la lucha de los pueblos contra las políticas neoliberales de los gobiernos. Hay gobiernos que no pueden definirse como progresistas ni de izquierda, porque permiten el extractivismo minero y los agronegocios, que dejan a un lado los parámetros de sustentabilidad y destruyen el medio ambiente, señaló el investigador social.

¿Qué verdaderamente se puede caracterizar como izquierda?, preguntó Anguiano, indicando que solo aquello que ataque la discriminación, el despojo, la opresión, es decir acabar con el capitalismo. “No puede haber más izquierda que la anticapitalista, la de abajo, con pueblos originarios, campesinos, proletarios, en donde se luche contra el poder y el capital, por una igualdad verdadera, por la autogestión y autonomía”, expuso.

Para el día de mañana viernes a las 16:00 hrs. se contará con la participación de Paulina Fernández y Magda Gómez. Posteriormente a las 19:00 hrs, darán su palabra Alicia Castellanos, Luis Hernández Navarro y la Comisión Sexta del EZLN, a l@s cuales se podrá sintonizar por la página enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx

AUDIOS: https://radiozapatista.org/?p=20824

Fotos: Área de Comunicación Abejas de Acteal y Pozol

Sub Moisés anuncia casi 4 toneladas de café para los herman@s migrantes de EEUU