Sorry, this entry is only available in Español. For the sake of viewer convenience, the content is shown below in the alternative language. You may click the link to switch the active language.

Festival CompARTE por la humanidad

27 de julio de 2016

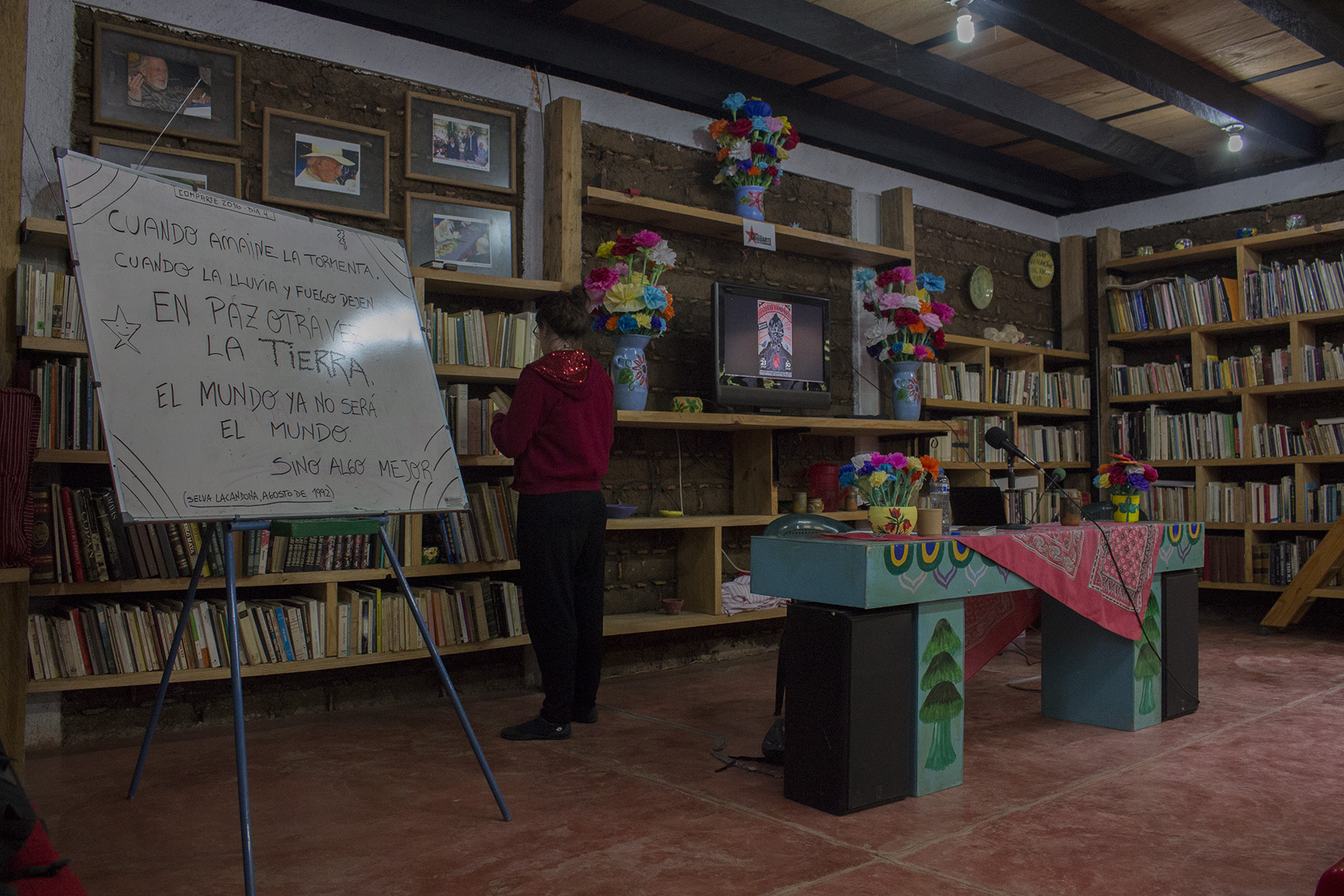

Cideci / Universidad de la Tierra Chiapas

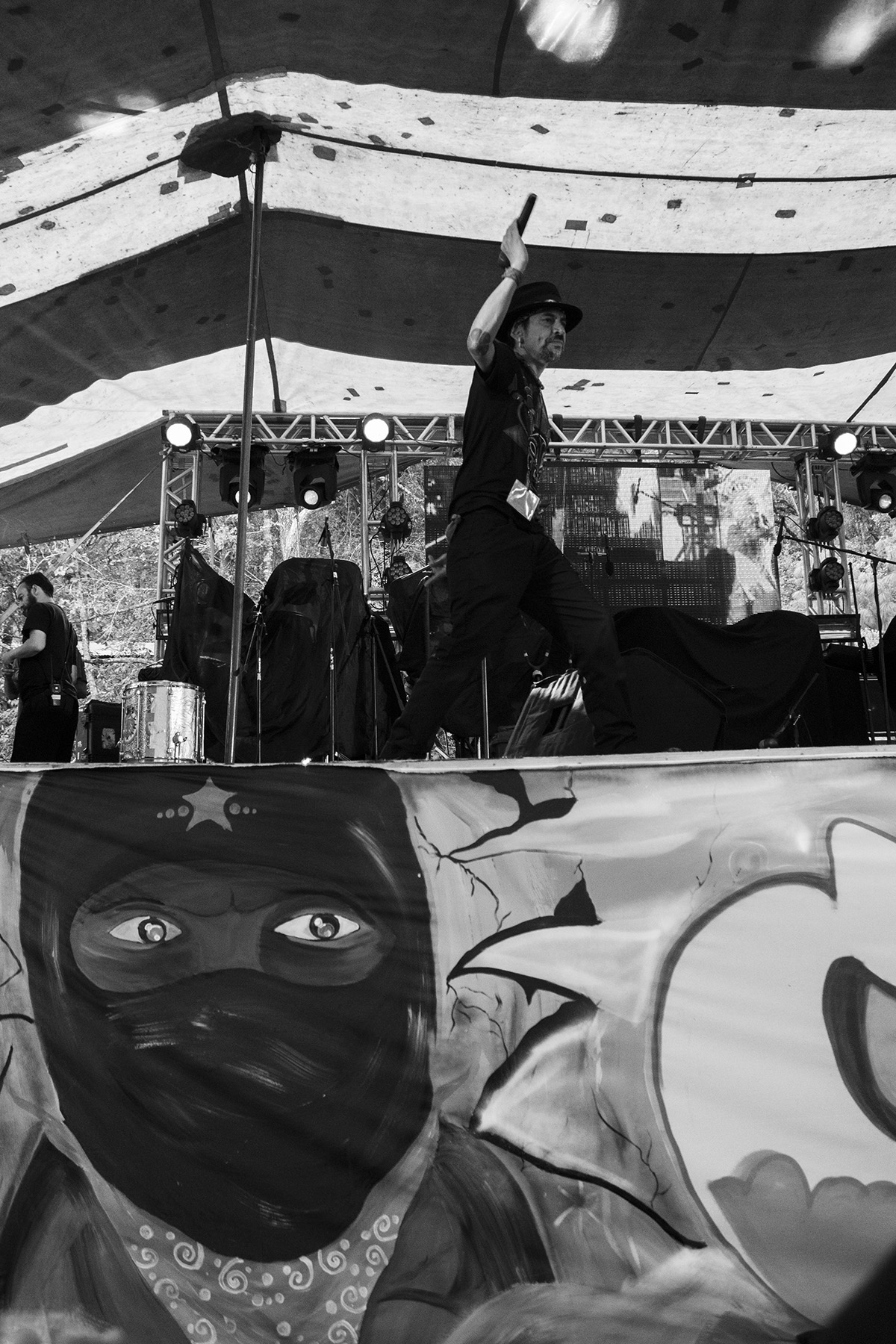

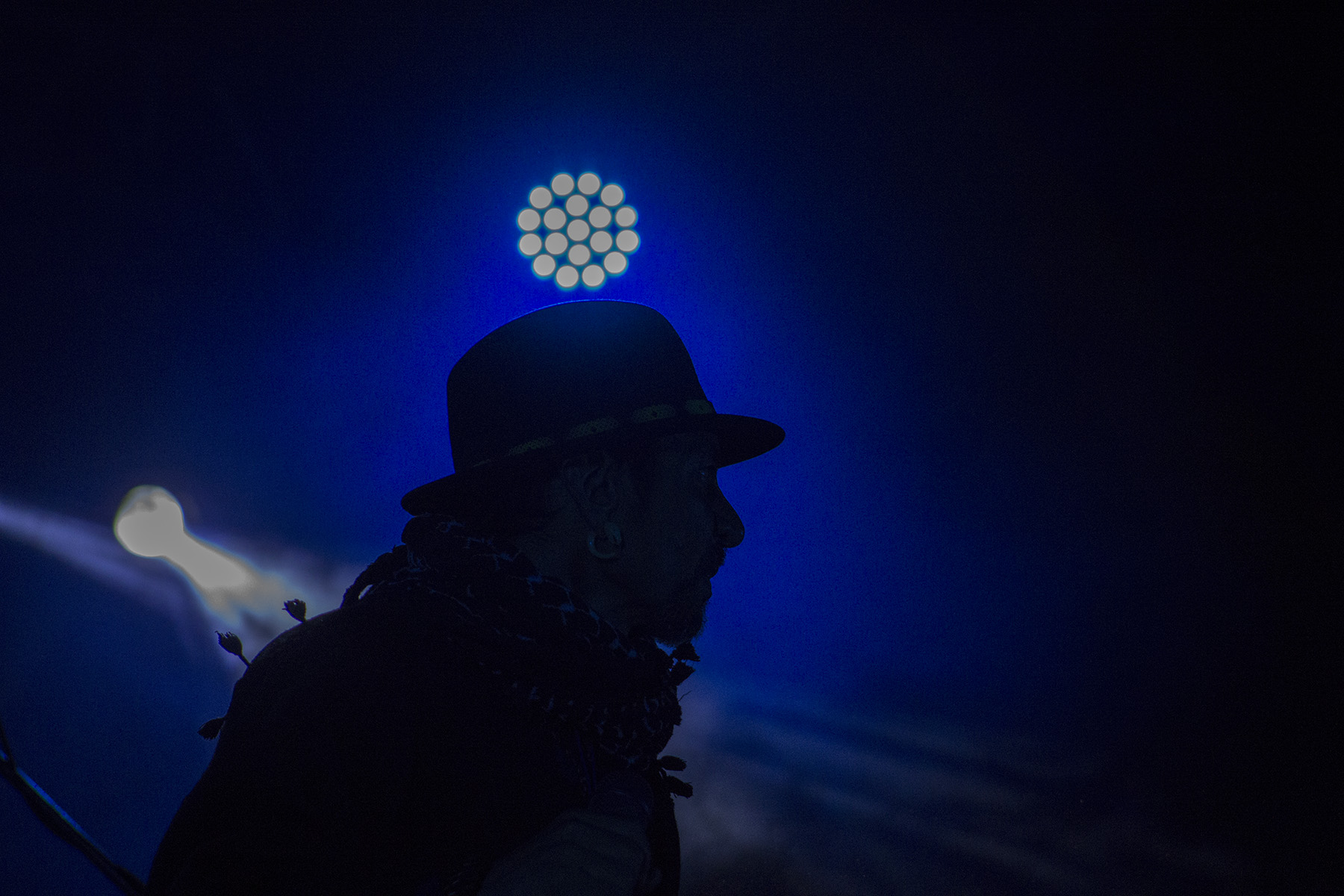

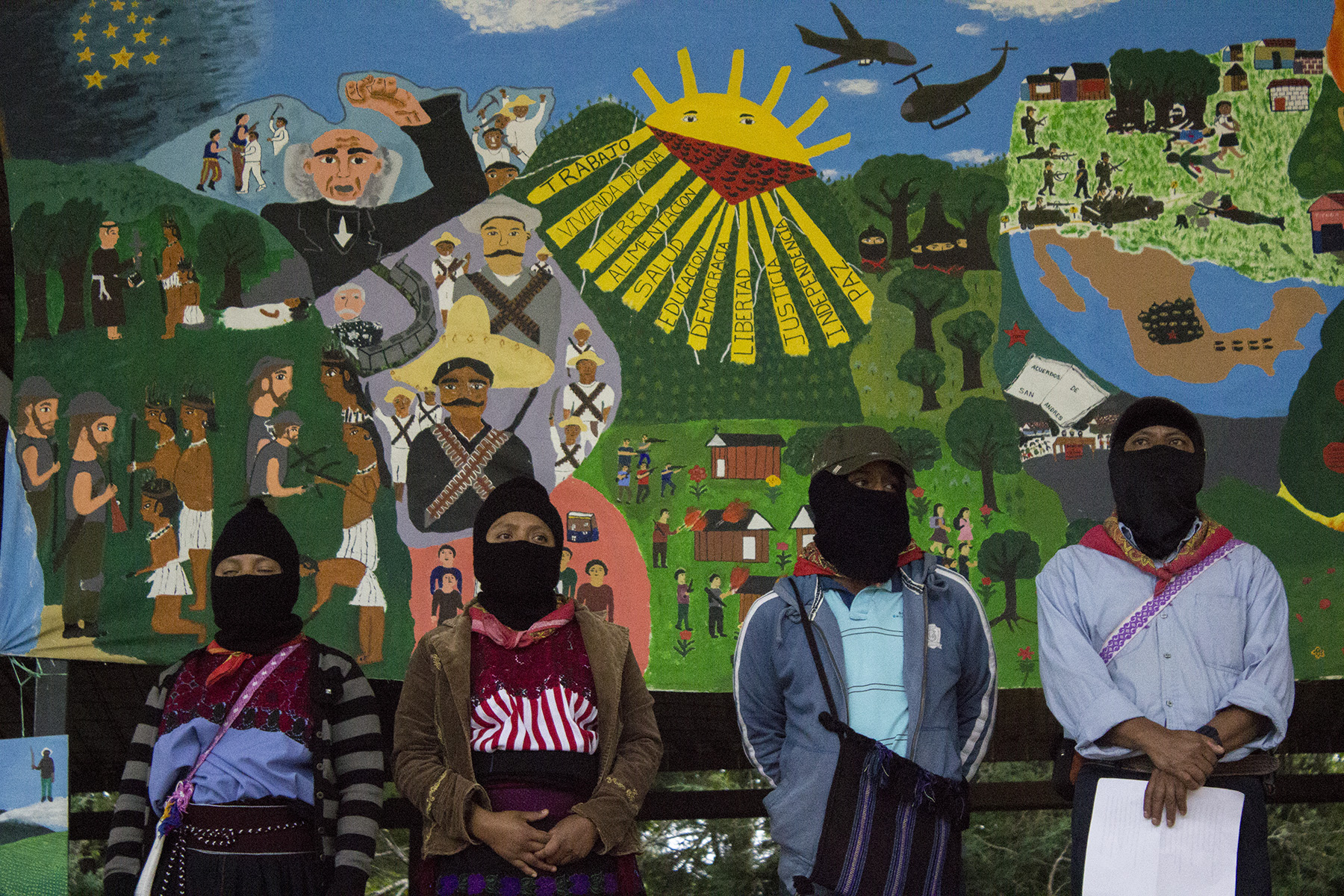

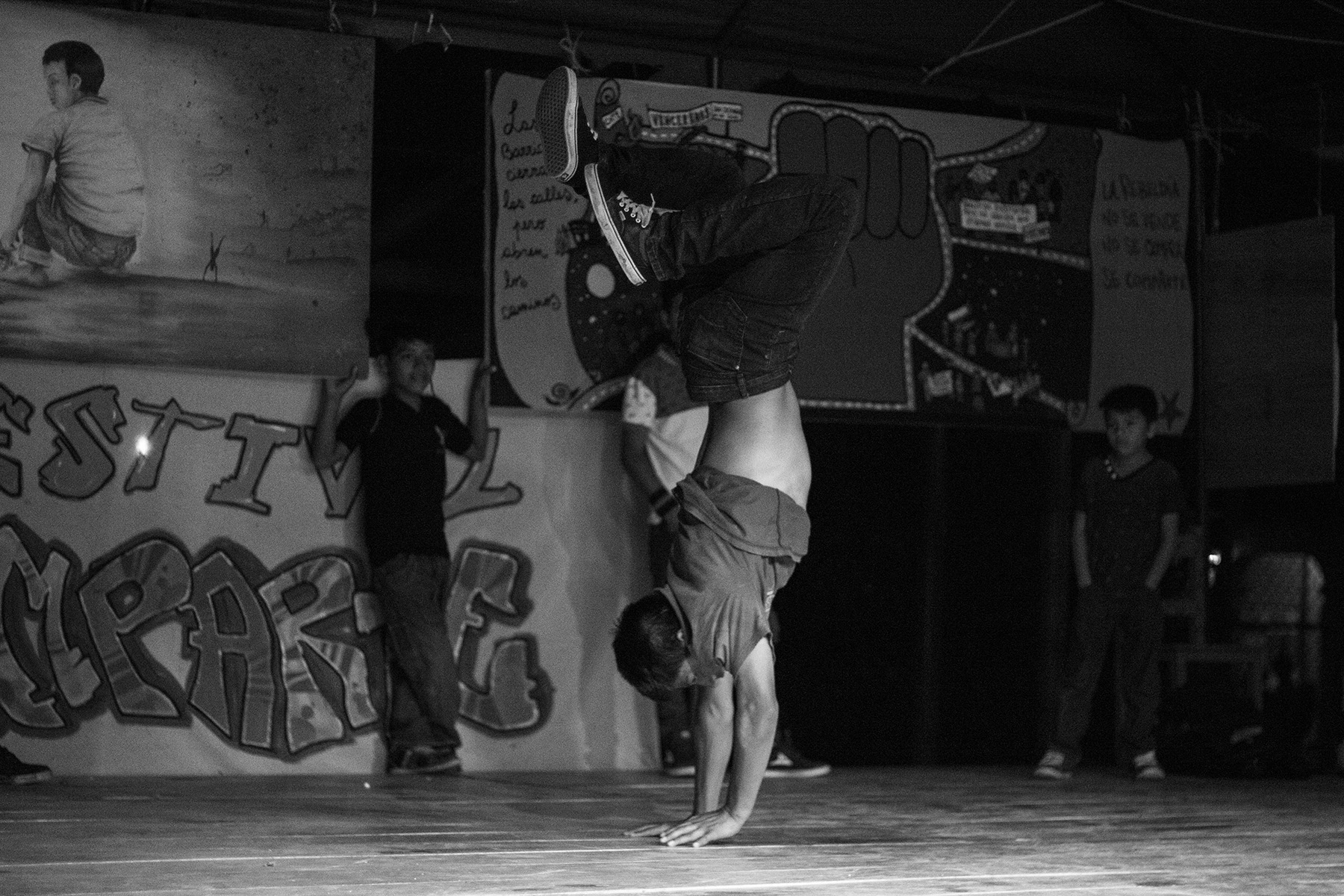

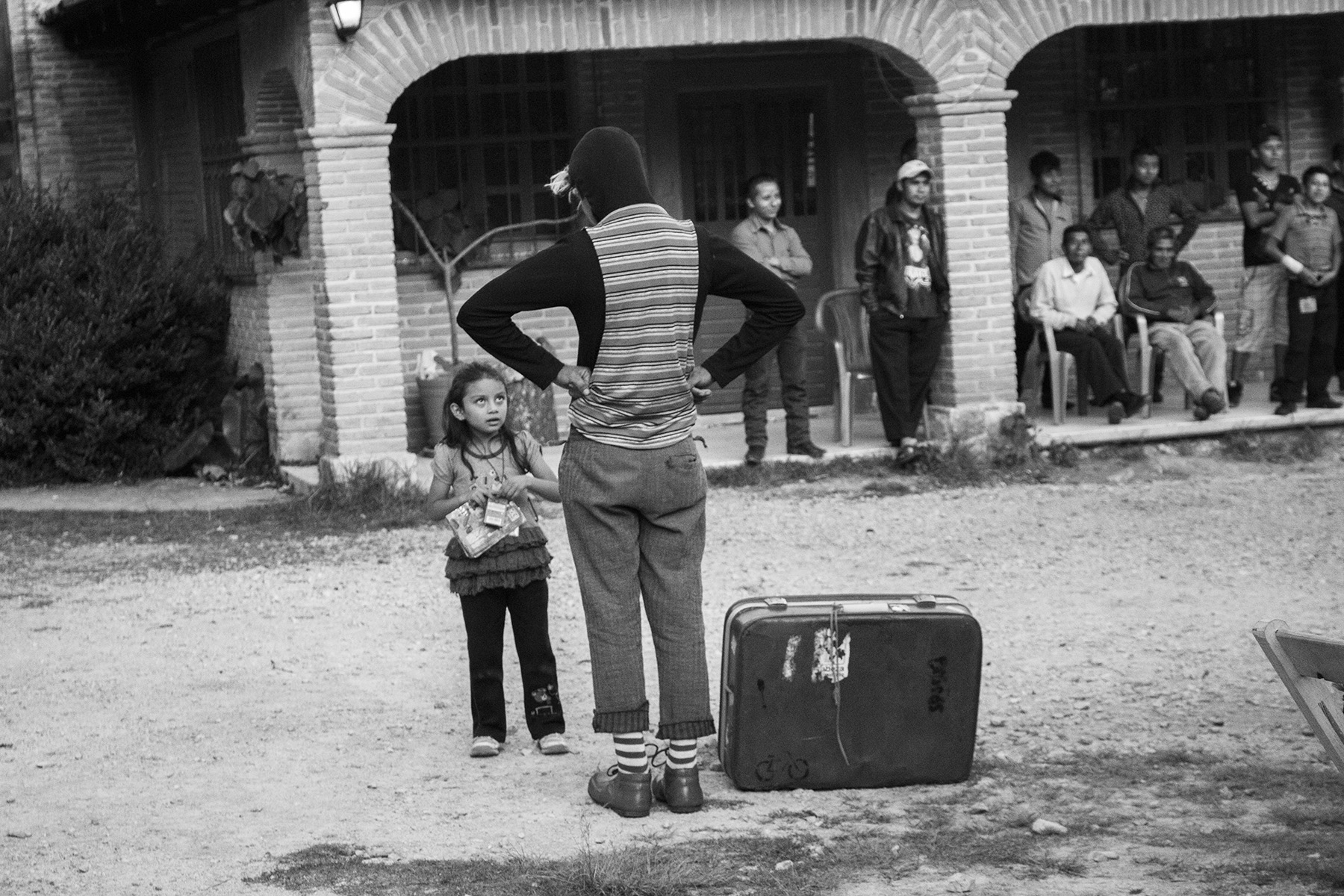

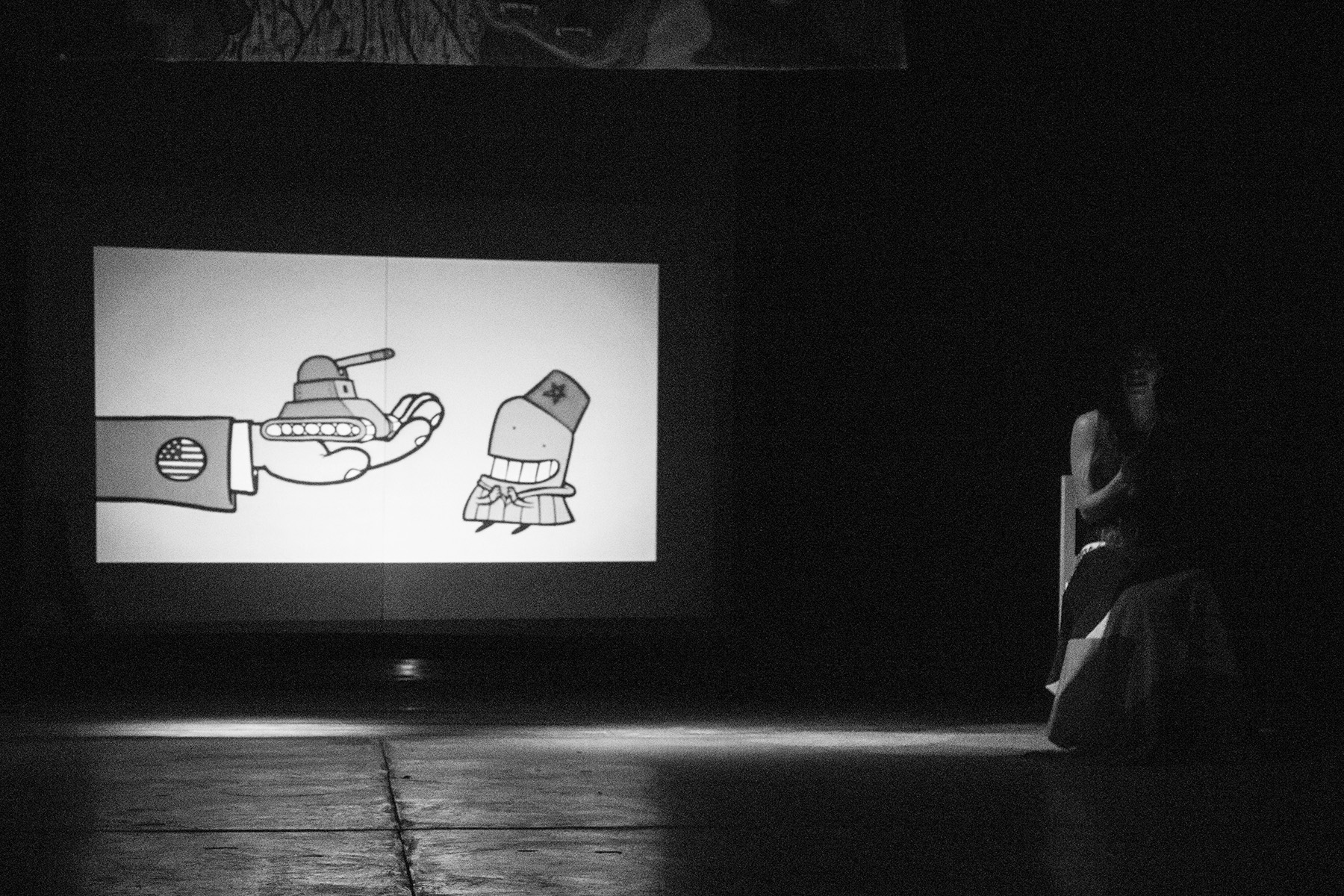

Miércoles 27 de julio.- Jovel-San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas. Conforme han pasado los días el festival #CompArte por la Humanidad se ha ido nutriendo de más participaciones por parte de las compañeras y compañeros que han llegado para realizar sus presentaciones, pero también para admirarlas, para re-conocerse, mirarse en el espejo sentido del otro, otra, otroa, el arte de la vida.

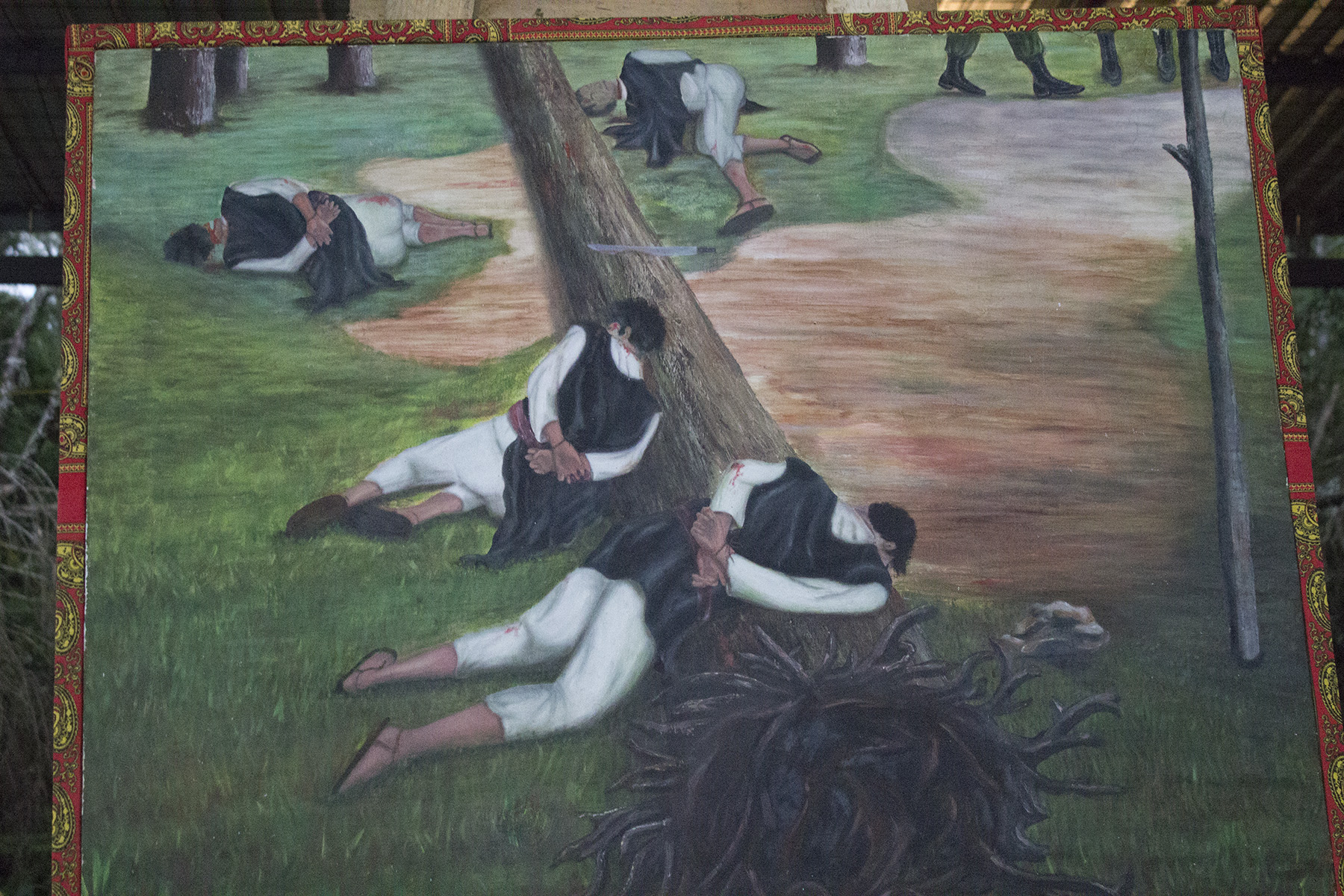

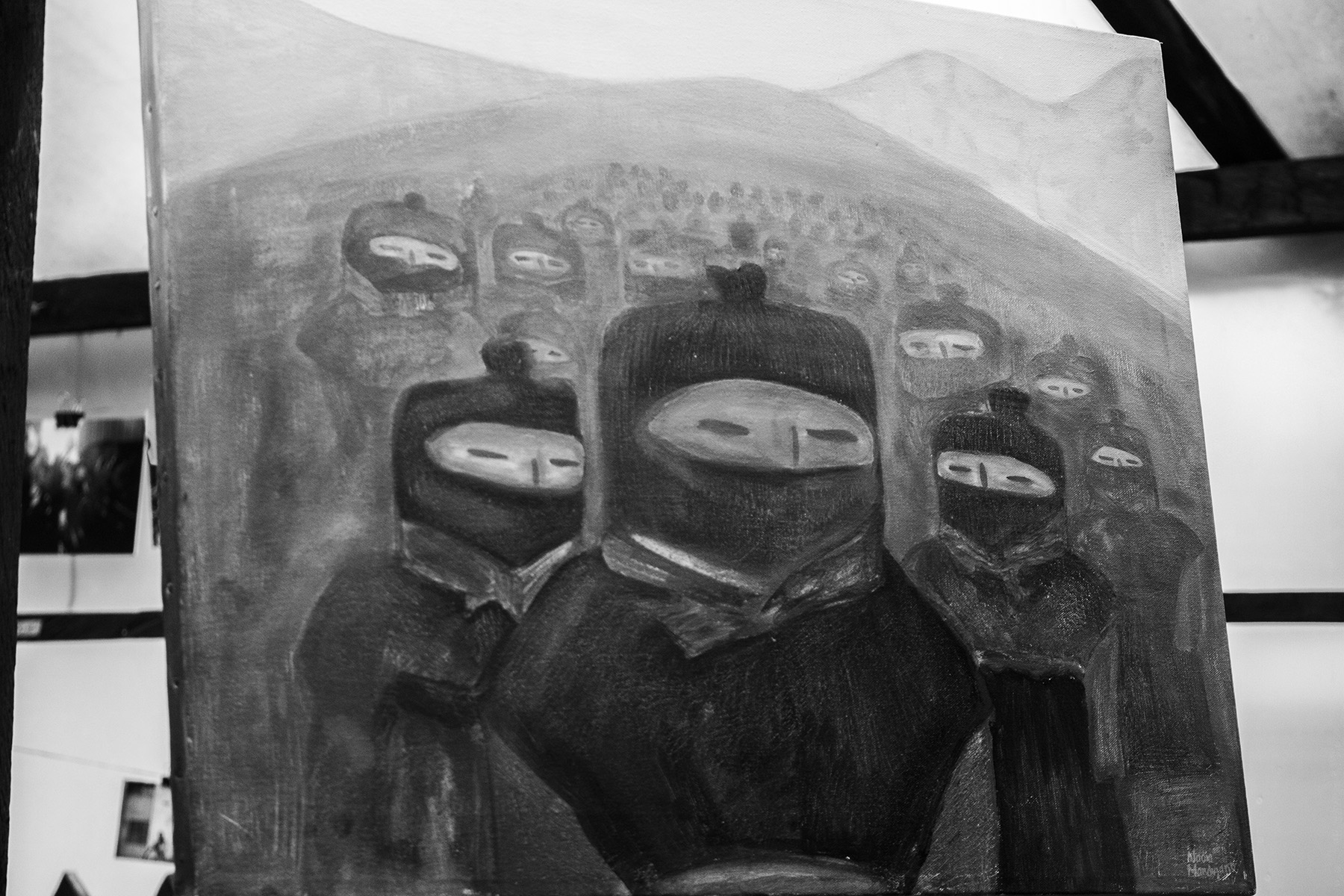

El Cideci Unitierra Chiapas, espacio donde de por sí se mezclan los colores que buscan dar honor al corazón de los pueblos, está ahora iluminado por el arte compartido por quienes acuden de las distintas geografías. Caminado a través de este Centro Indígena, Universidad, unoa puede ser testigo de un espacio y tiempo saturado por el multicolor de un bordado que bien pudiera ser la representación viva del sueño imaginado por la compañera Comandanta Ramona.

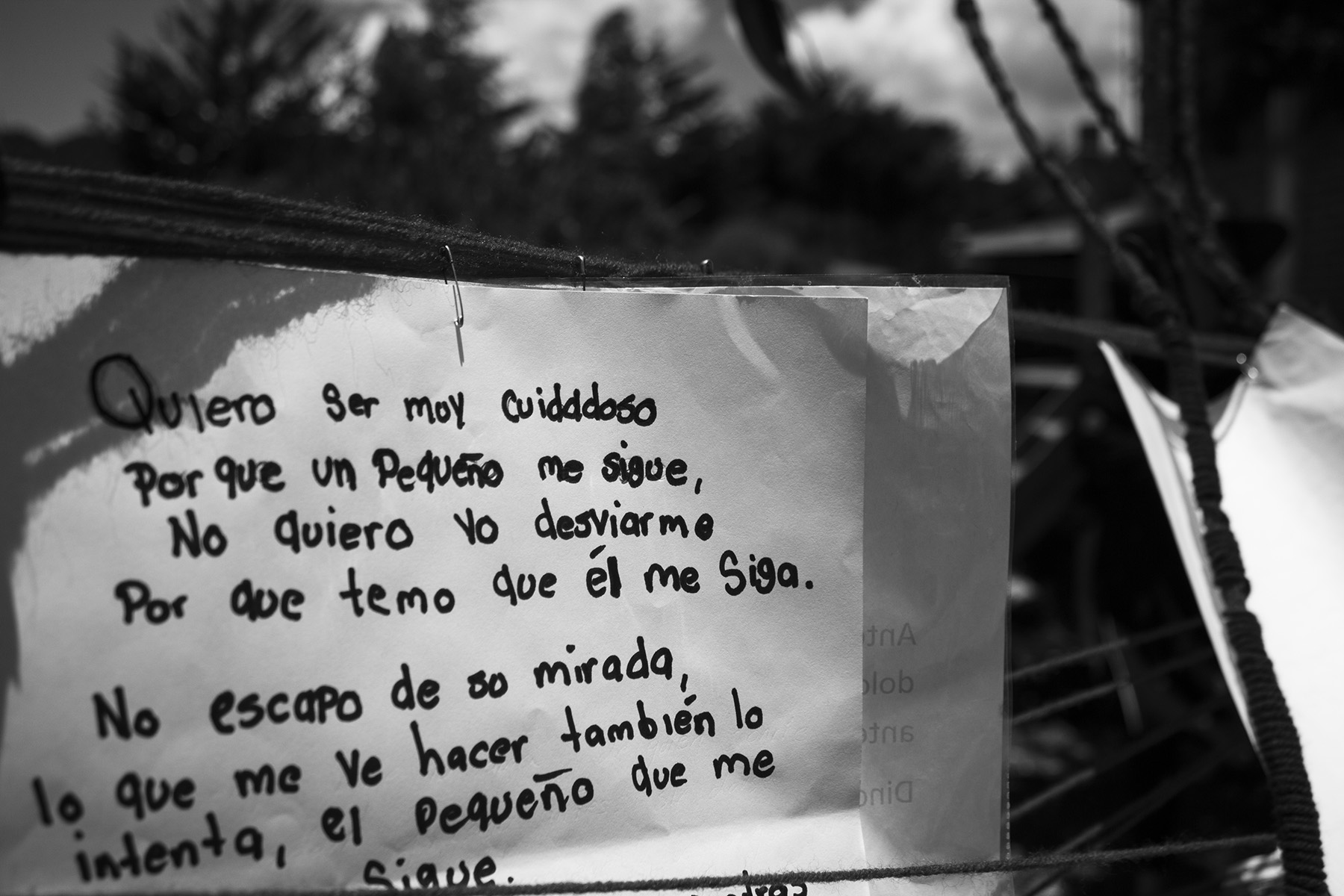

El programa de participaciones, como el arte, va siendo modificado y ampliado, como el ahora anunciado por parte del las compañeros y compañeros zapatistas. Unoa puede caminar y contemplar cómo la creación artística se vuelve pretexto en cada pequeño rincón para compartir sueños, compañerismo, transmisión de conocimientos, pensares, sentires, saberes y técnicas.

En las entrevistas y algunas de las presentaciones que pudimos recoger para ser compartidas y utilizadas de manera libre, ustedes podrán escuchar de viva voz el corazón puesto, las expectativas superadas. Es pues otro festival, porque es nuestro, es colectivo, es el arte de abajo, la transgresión lograda por los cientos de manos que ponen su empeño por así lograrlo en cada rima, trazo, sonido, movimiento, sonrisa, lágrima, esfuerzo compartido.

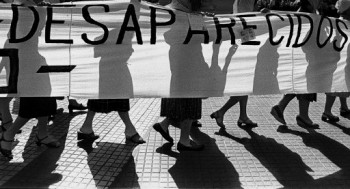

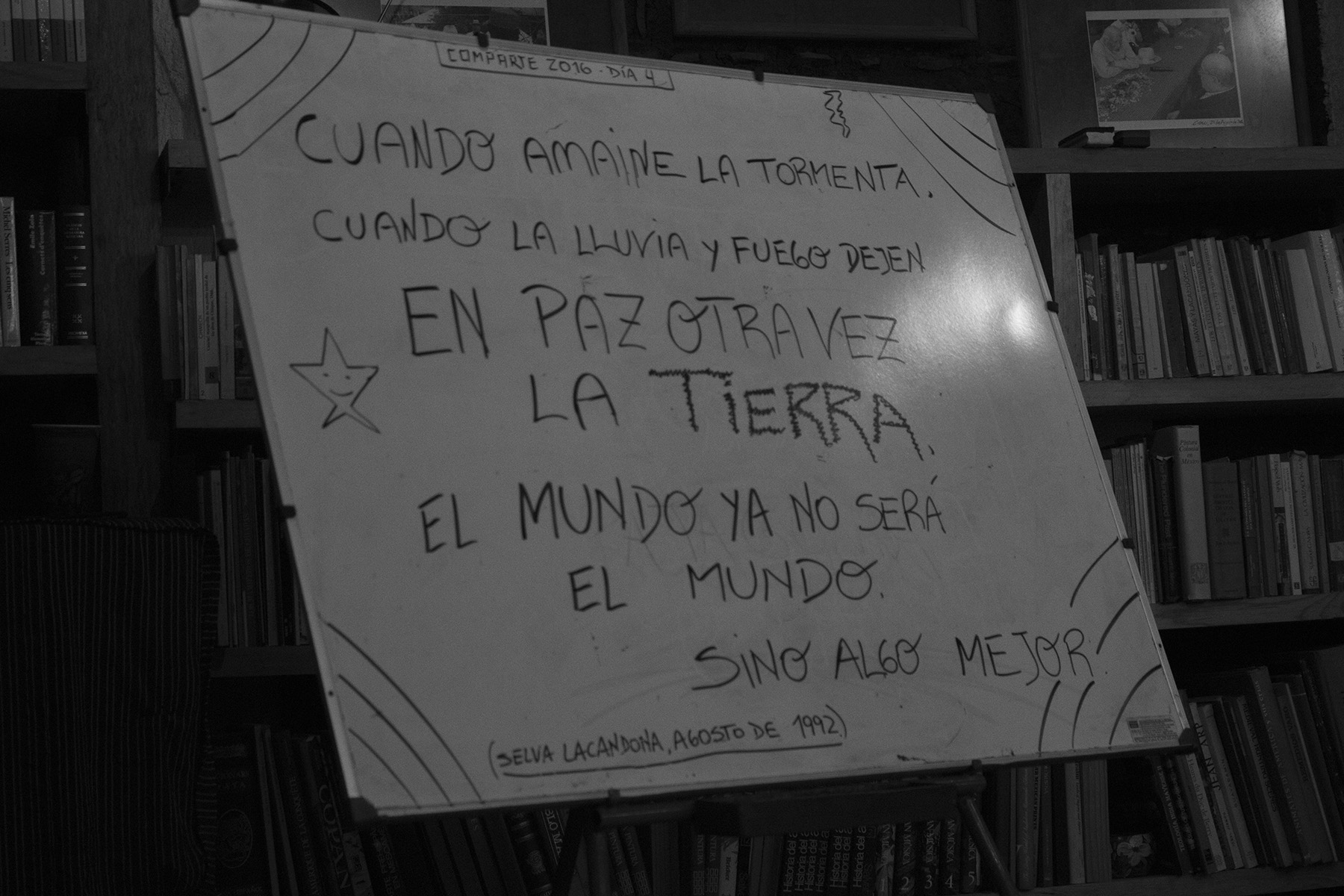

Mientras la tempestad del capital azota nuestra América y Planeta Tierrra, busca separarnos, destruirnos, el arte teje ese puente que entrelaza y trasforma corazones, esperanzas; porque el lenguaje del arte une, nos permite seguir viviendo y soñando.

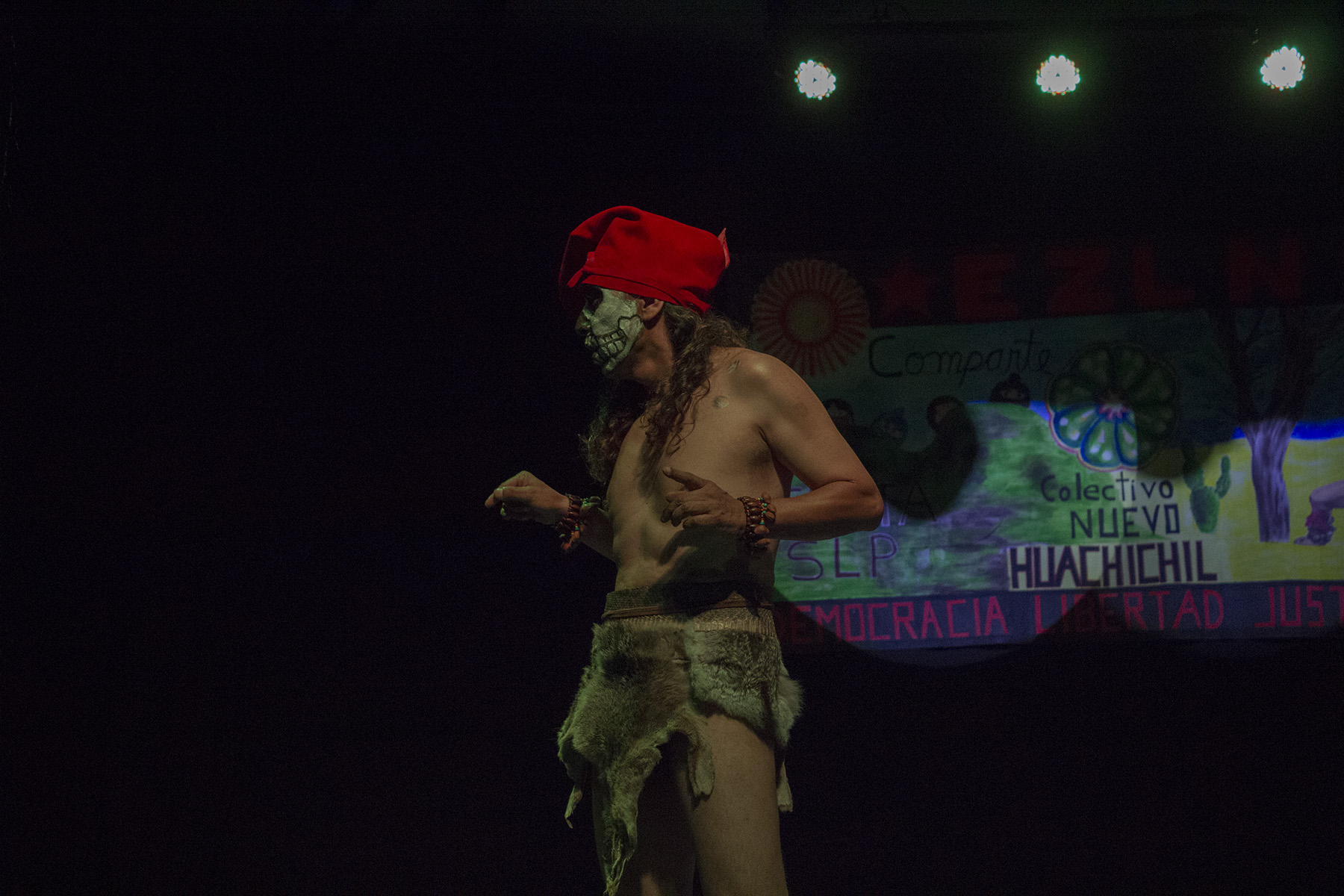

Gitanos Teatro llegó al compArte con El Combo Gitano, que incluye Nahualito, El viaje de Rita y Lilit o la rebeldía, piezas que presentan en comunidades marginales, alternativas y en lucha, pues el arte es una herramienta para convivir, rebelarnos y gritar contra lo que no estamos de acuerdo:

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/gitanosteatro.mp3[/podcast]

Natalia Arcos y Alessandro Zagato, del Grupo de Investigación en Arte y Política, compartieron que en el zapatismo también se insinua un nuevo paradigma artístico y estético colectivo:

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/giap.mp3[/podcast]

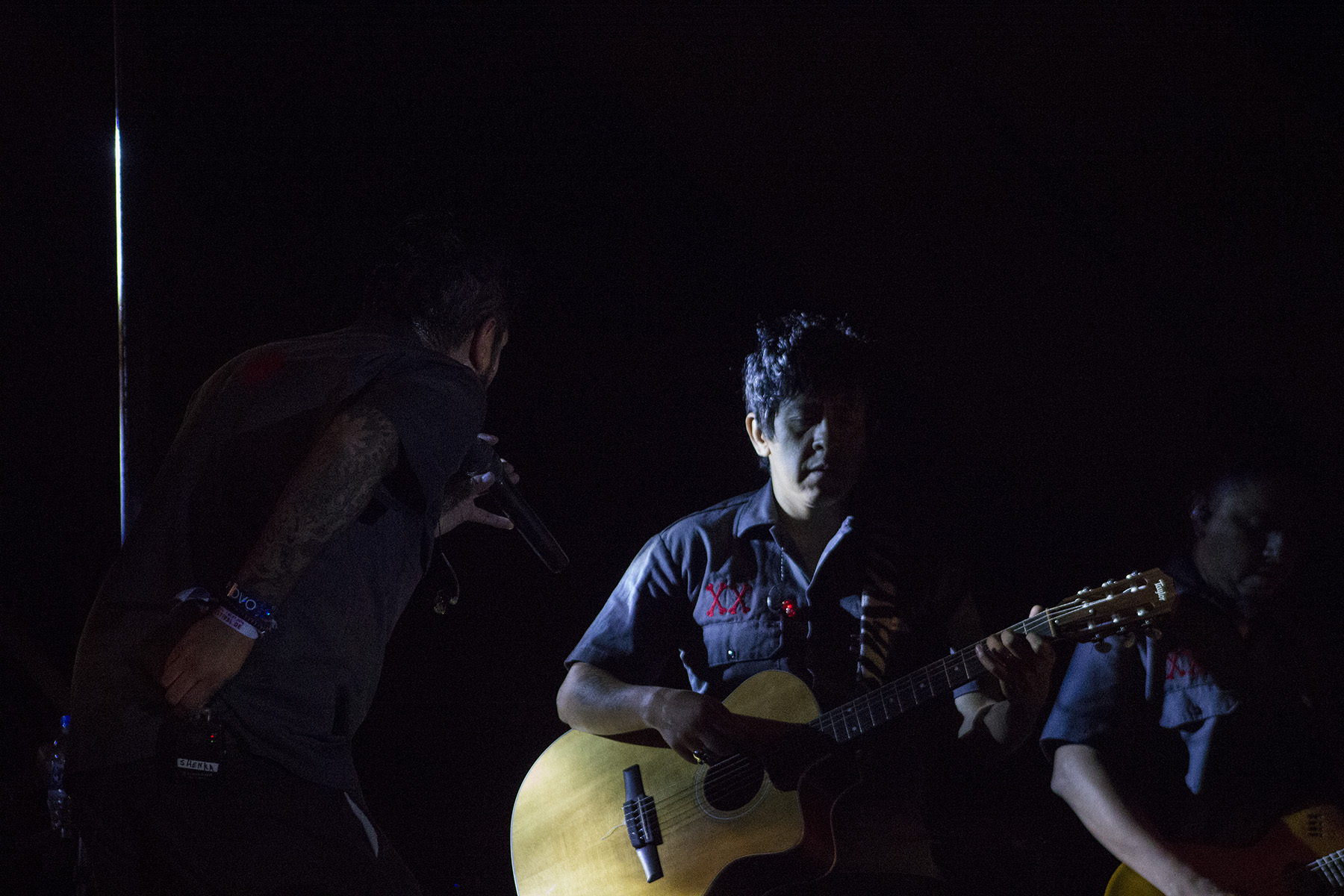

Desde la comunidad de Chalmita en el Estado de Mèxico, Mariel Henry y Diego Corvalan, Los Chalanes del Amor, presentaron música popular latinoamericana como Caminito Verde de Colombia y La Bamba con ritmos abuelitos e instrumentos como la marimbula, tres cubano, requinto jarocho y jarana, todo ello para amar a la memoria, la sinceridad y las ganas de ser nosotrxs mismxs:

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/chalanesdelamor.mp3[/podcast]

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/chalanesbamba.mp3[/podcast]

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/chalanescaminitoverde.mp3[/podcast]

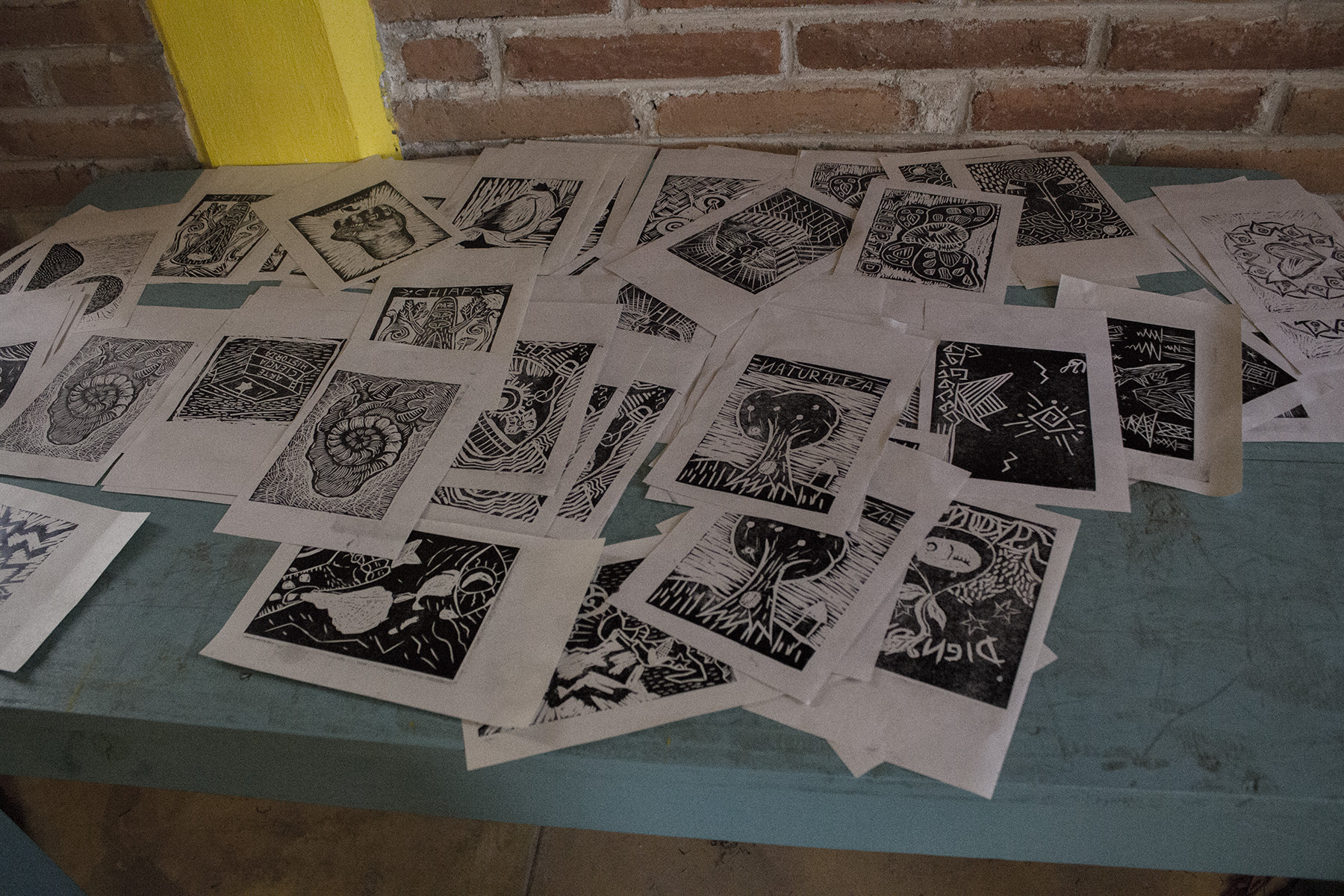

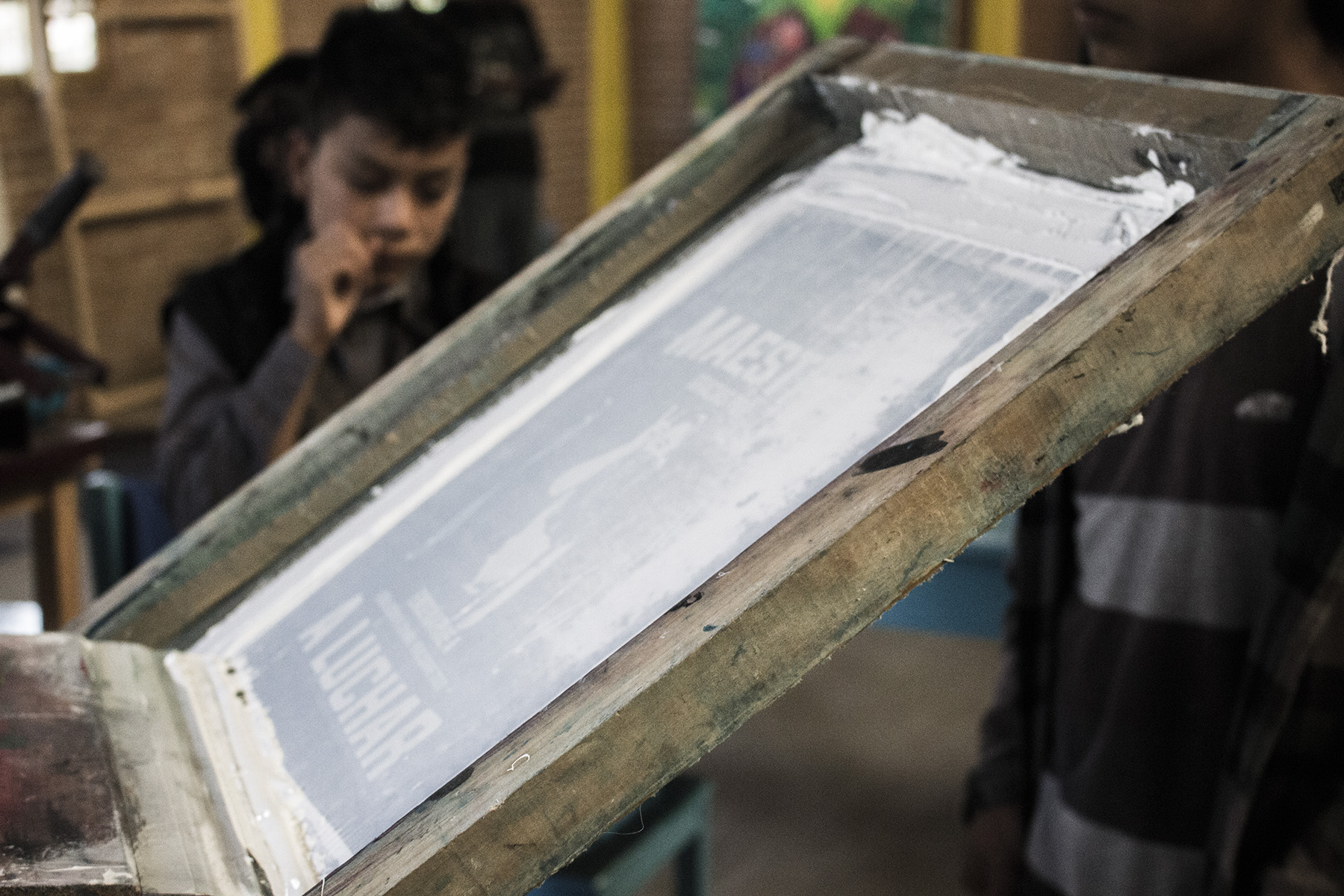

Desde Puebla, Óscar Navarro y Jiro Martínez, de los colectivos Tamaa y Grieta Negra, compArtieron una muestra de su gráfica:

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/tamaygrietanegra.mp3[/podcast]

Katia Reyes e Isac Bañuelos juntaron cuentos y opera en lenguas originarias como la canción tsotsil “Canto de amor” del cuento “Y la tortuga dijo”:

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/cuentoopera.mp3[/podcast]

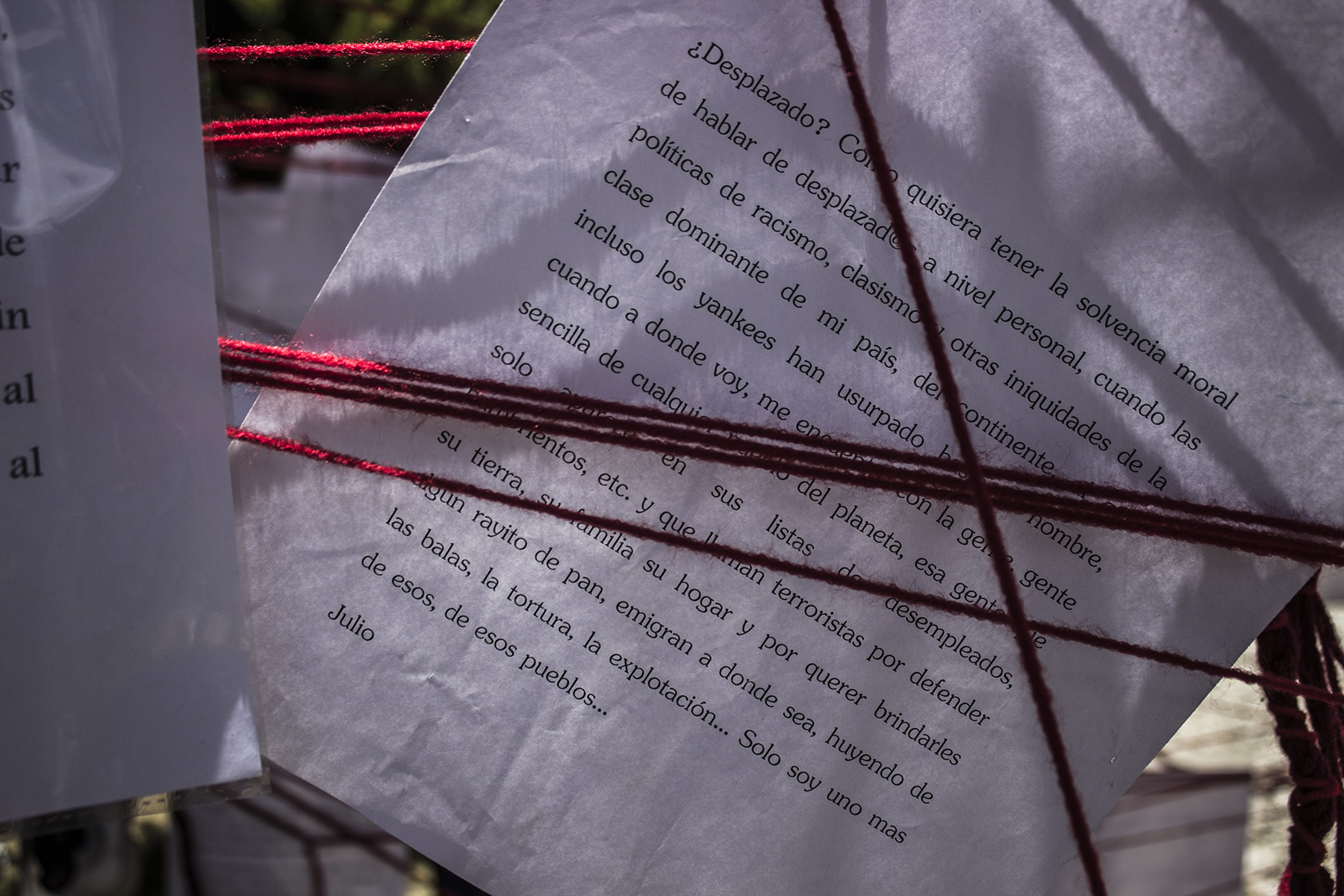

Desde la ciudad de México, Psiquesonimas combinó la palabra zapatista y la música tradicional para narrar-cantar-contar piezas como un corrido sobre los desplazados de San Pedro Polhó tras las agresiones paramilitares de 1997 y 1998 con un son calentano de Guerrero:

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/psiquesonimas.mp3[/podcast]

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/psiquesonimasdos.mp3[/podcast]

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/psiquesonimastres.mp3[/podcast]

Norma, del proyecto La mal hablada, mostró con su arte callejero, sus dibujos y sus colores que el arte es hacer comunidad:

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/lamalhablada.mp3[/podcast]

El Grupo Chintete de la comunidad de Almolonga, en el municipio de Tixtla, Guerrero recuerda a los normalistas de Ayotzinapa y lucha para que la alegría de su música se sobreponga a la tristeza y la violencia en Guerrero:

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/chintete.mp3[/podcast]

El Ensamble Blanco y Negro dedicó el Nocturno de Chopin a las familias desplazadas y víctimas de la violencia:

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/ensambleblancoynegro.mp3[/podcast]

Desde Iztapalapa, Jacqueline González relató historias como “El corazón del maíz mató al gran juez”, de origen huasteco, y “¿Por qué existe el día y la noche?” de la lengua Kiliwa, cuya comunidad es de 100 habitantes y 4 hablantes:

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/jacquelinegonzalez.mp3[/podcast]

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/jacquelinedos.mp3[/podcast]

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/jacquelinetres.mp3[/podcast]

Checo Valdez y Lola compArtieron que después de 10 años y del fortuito y emblemático Mural de Taniperla, Pintar Obedeciendo ha logrado que las personas de las comunidades se animen a comunicarse, pintar y contar historias:

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/pintarobedeciendo.mp3[/podcast]

Desde Porto Alegre, Brasil, Marcelo Argento del colectivo Digna Rabia compartió ska y cumbia:

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/marcelouno.mp3[/podcast]

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/marcelodos.mp3[/podcast]

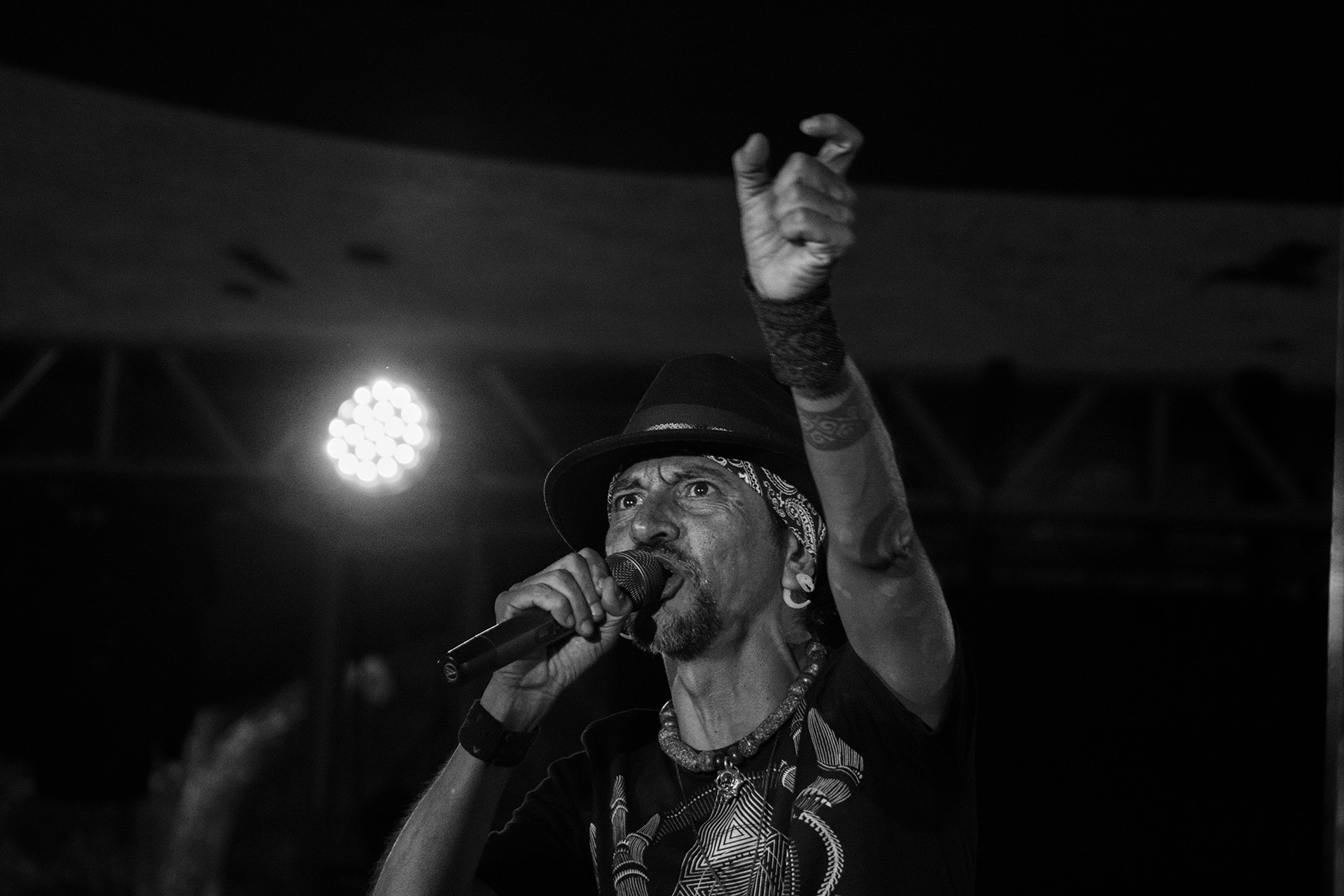

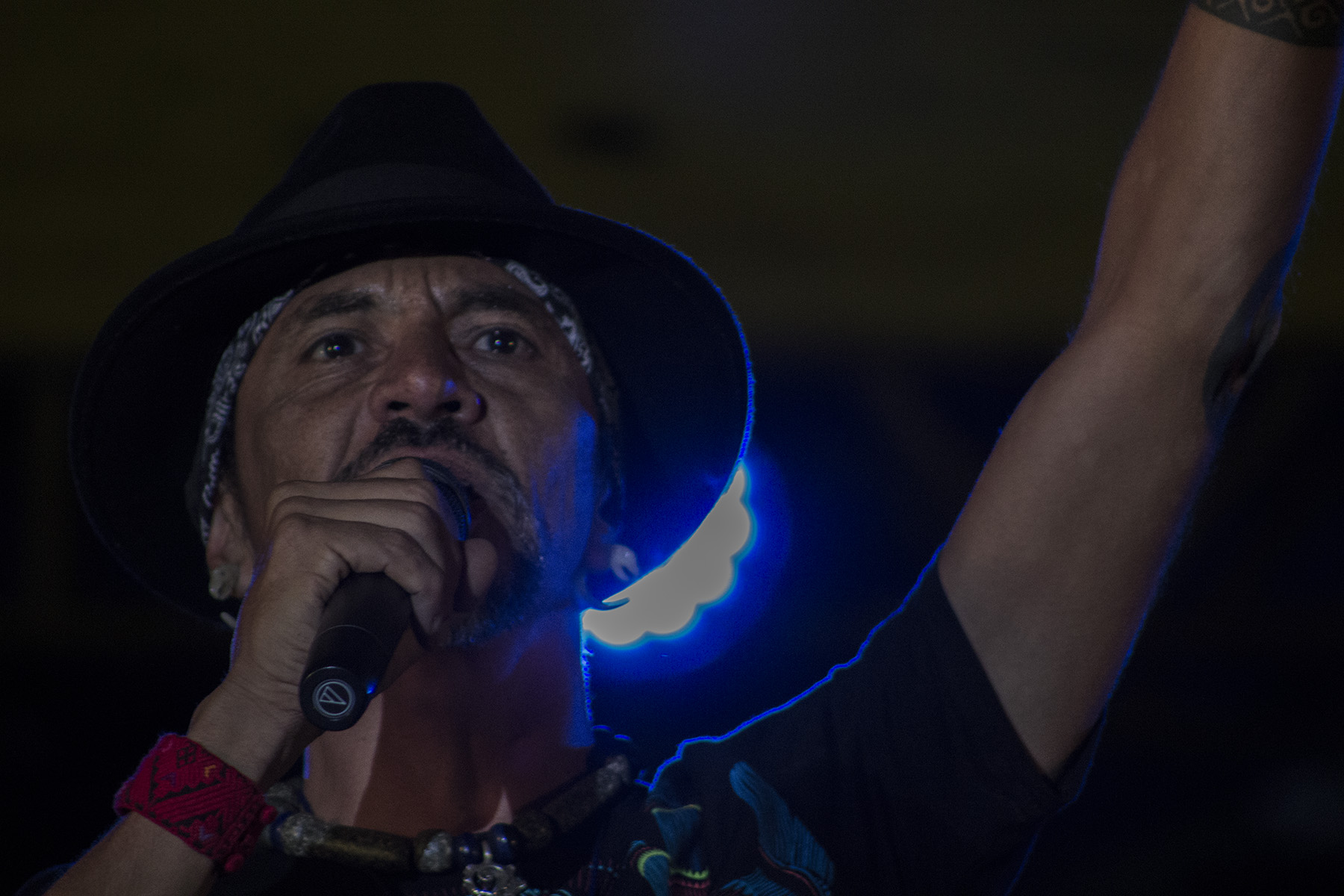

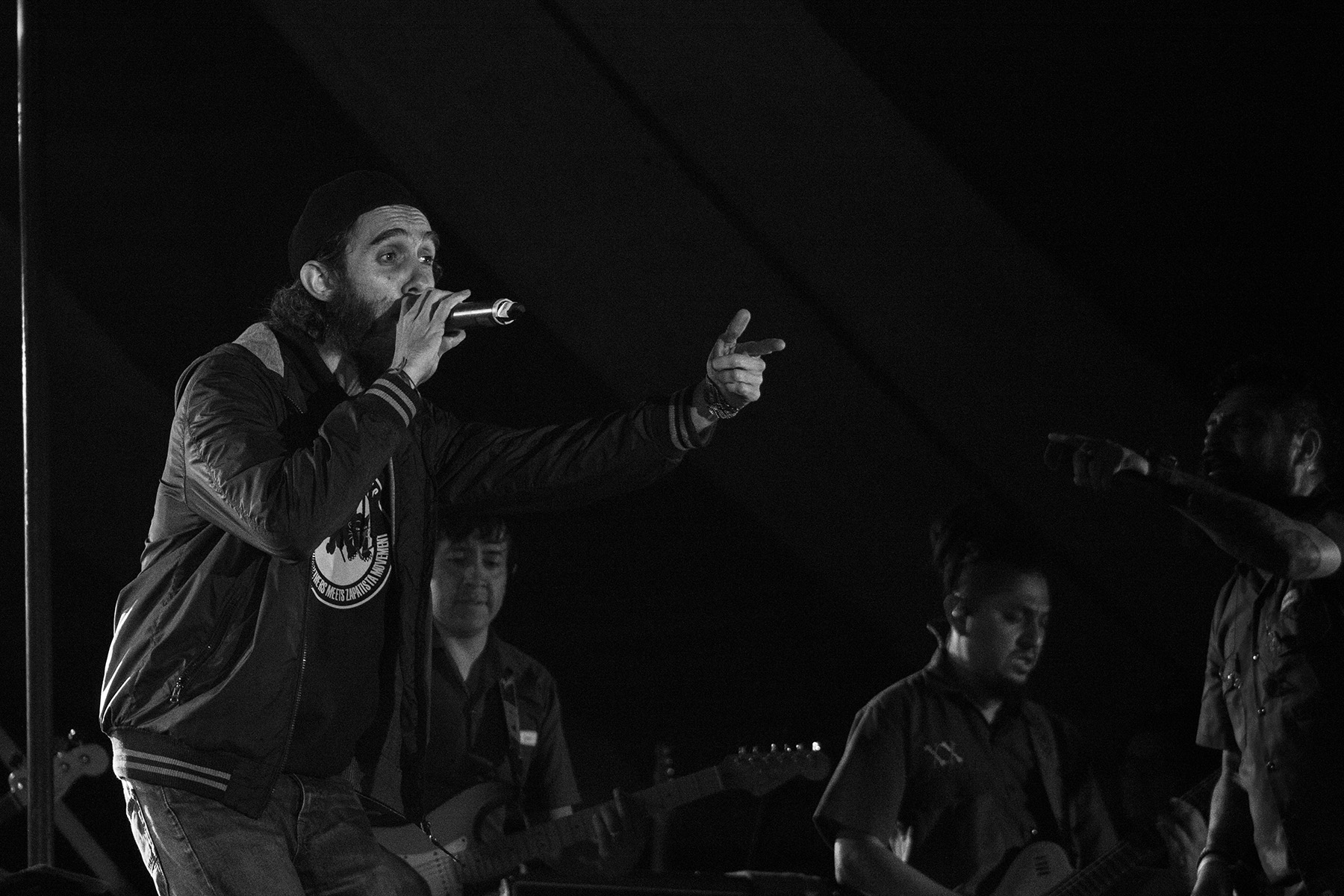

Desde el centro de Lima, Perú, Pedro Mo contagió su rabia, indignación, combate y transformación comunitaria por medio del hip-hop:

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/pedromo.mp3[/podcast]

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/pedrodos.mp3[/podcast]

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/pedrotres.mp3[/podcast]

X Malton y Rogelio Martínez del CLETA compartieron poesía y composiciones:

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/xmalton.mp3[/podcast]

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/poemadexmalton.mp3[/podcast]

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/rojelioyxmalton.mp3[/podcast]

Emory Douglas, el Ministerio de Cultura del Black Panther Party de los años ’60 en San Francisco, California, compArtió su experiencia revolucionaria y artística y la exposición Zapantera sobre el trabajo colaborativo con las comunidad zapatistas:

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/rzchiapas/emorydouglas.mp3[/podcast]