(Español) “Bailando la libertad” – tercer día del CompArte de Danza “Báilate otro mundo”

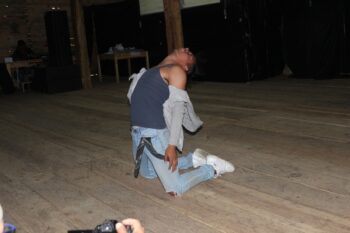

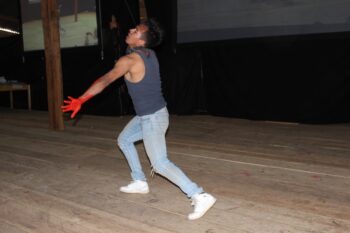

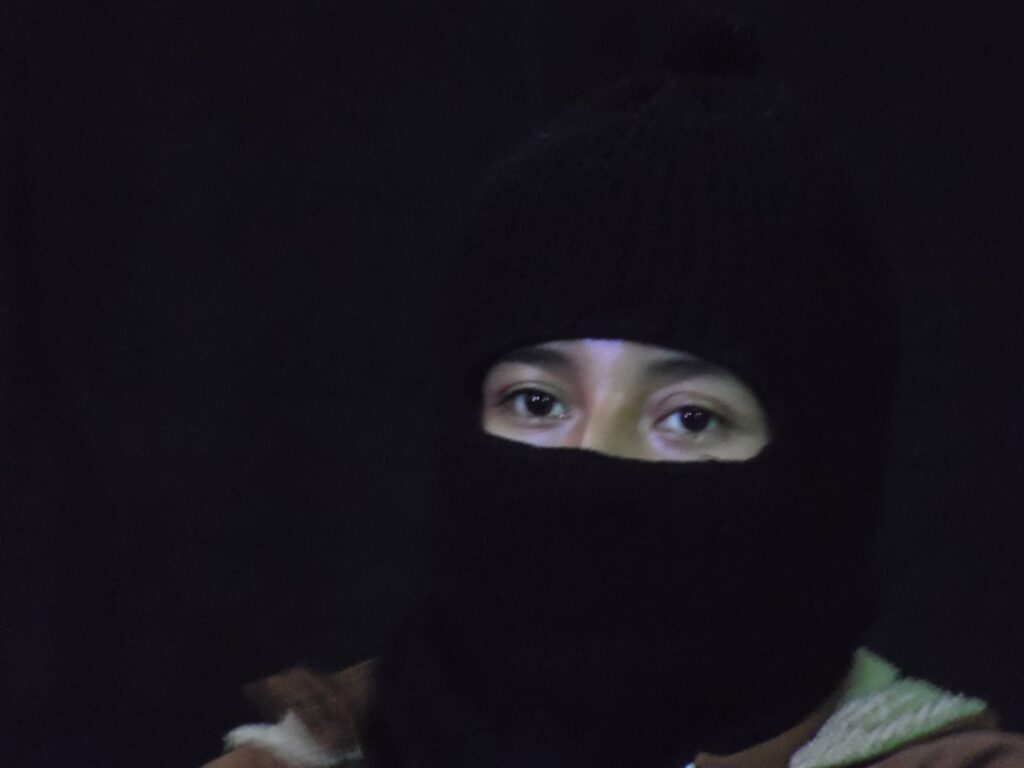

Liberarse de la esclavitud del capital, del consumo, de las pequeñas y grandes cosas que nos atan a vidas sin vida y volar, bailando en el aire.

El tercer día del CompArte de Danza 2019 “Báilate otro mundo” continuó ayer 18 de diciembre en el caracol Jacinto Canek, en las instalaciones del Cideci, en San Cristóbal de Las Casas.

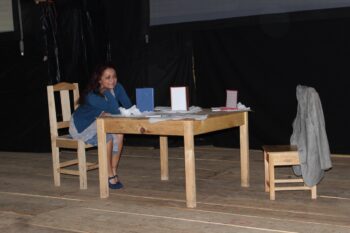

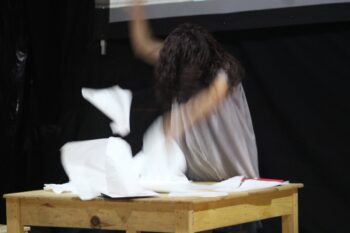

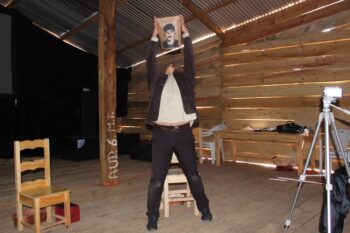

La jornada inició con el “divertimento coreográfico” “Tríptico”, del Colectivo Sociodanza, colectivo de danza contemporánea del Faro del Oriente en la Ciudad de México, en el que, con música de Vivaldi y coreografía de Miriam Álvarez, se abordan temas tan diversos como la memoria del movimiento del 68 a las encrucijadas en las que cada decisión implica la castración de otra posibilidad.

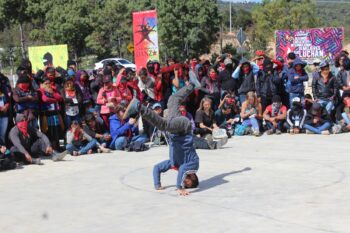

Victoria Arts se presentó de nuevo con las obras de ballet “Ave María” y “Carmen”, deslumbrando una vez más a un público en su mayoría zapatista.

El Colectivo Sociodanza se presentó también con la pieza “Esclavo”, un comentario sobre la esclavitud que con frecuencia implica la dependencia tecnológica y la afición por el consumo.

Los colectivos Marabunta y El Puente invitaron al público a volar hacia otros mundos posibles por medio de la danza aérea, y el colectivo GACHO presentó “Cempasúchitl, flores de la memoria”.

La Compañía Tierra Independiente presentó la extraordinaria pieza “Coreografías unipersonales y colectivas”.

Por su parte, Jorge Izquierdo presentó la plática “Ver, observar, percibir para interpretar la danza”, sobre la fotografía de danza y la creación.

En la tarde se impartieron también talleres abiertos de danza contemporánea, expresión corporal, malabar, danza africana y danza árabe.

El CompArte de Danza 2019 continúa hoy en el caracol Jacinto Canek en San Cristóbal de Las Casas, y termina mañana, viernes 20 de diciembre.

Ve un poco de la pieza “Tríptico” del colectivo Sociodanza:

Fotos (Radio Zapatista y Colectivo Transdisciplinario de Investigaciones Críticas (COTRIC)):