News

THEM AND US. VII. The Smallest Ones 4. The Compañeras: assuming the position.

Them and Us VII.

The Smallest of Them All 4.

The Compañeras: Taking on the cargo*

*Cargo, a duty or task, refers here to a designated position of responsibility and authority.

February 2013

There is nothing more subversive and irreverent as a group of

women from below saying, to others and to themselves: “we.”

Don Durito

Note: Below are more fragments from the Zapatista women’s ‘sharing,’ only now the compañeras are discussing their work and the current problems that they face in their cargos of leadership, the teaching and carrying out of justice, and the managing of resources, along with some reflection on the thorny issue of “gender equity” in the construction of a world that proposes to be inclusive and tolerant, a world where “no one is more, no one is less.”

-*-

(…)

Yes, we have had to settle cases like this. Once we had a case—I will comment here on what the other compañera already mentioned—when we had barely entered the Junta [Good Government Council], they put the two of us in charge of a team and a problem was brought to us. A compañera complained that she was being mistreated by her husband. It is an incredible story and it was a really ugly situation for us. The compañera said:

“I want a separation from my husband,” but this now ex compa already had two wives.

We investigated the situation. We called the children of the first wife and of the second, and from there we started to come up with a solution. That’s why it took us awhile, the situation was really messed up. We had asked the compañera:

“And what is it that he did to you?” thinking that he had only hit her.

No, this darned guy had hung the compañera from by her feet and hit her, same as with two of his other children. And so we had to find a solution. What was our solution? The compañera asked for a separation, so we did this by distributing their belongings between the first wife and her children, because it was the man who had committed the offense and we couldn’t leave her with nothing, and the second wife, because she already had a grown son. We didn’t leave anything to the man, we left the rest to the son so that our decision would be clear to the man. We divided up all of his things, this is how we solved the problem, we decided in favor of the compañera who had come to us to make her complaint.

(…)

-*-

-*-

(…)

Yolanda: We’re going to continue with what I am to talk about, which is a little bit about the law [Women’s Revolutionary Law]. As you know, this law was created precisely to address the situation that the compañeras lived on a daily basis. This is why it was created, because before the law they suffered a lot, as we have already heard and I won’t repeat now. This law is already written; we have it in the five caracoles.

(…)

But we see that it is very important that we study this law well, because if we don’t really understand what it is that this law tells us, as we have discussed a little bit in this zone, the same history can repeat itself again, where it is forgotten that woman is the giver of life, as we have heard happened before. If we don’t understand this law that we Zapatistas have, this could occur again.

This law was not made so that now women could give the orders, it wasn’t so that women could dominate their husbands, their compañeros; this is not what it means. That’s why we need to really study this law, because that is not the reality that we are going to create, nor do we want to follow the history that we have now, where the compañeros who are machistas [chauvinist] give the orders. But if we misinterpret this [law], the same thing could happen but where the compañeras will give the orders and the poor compañeros will be left out, and this is not what we want.

What we are after is something like a construction of humanity, this is what we are trying to change, and this requires another world. It is like the goal of everything we are doing, men and women, because as we have already heard, it isn’t a woman’s struggle and it isn’t a man’s struggle. When we’re talking about revolution they must go together, among all men and women, that is how struggle is made.

It can’t be that the compañeros say we are struggling here, making revolution, but only compañeros take on the cargos and the compañeras stay in the house. That is not a struggle for everyone. What we want is a struggle for everyone, men and women, this is what we want.

But let’s be clear that we are still learning this first law, it still makes us a little dizzy, because the truth is that as compañeras it is still very difficult for us to take on a cargo, any cargo.

(…)

-*-

(…)

You mentioned that there is a commission of honor and justice. What is its job and what is the role of the compañeras there?

On the question of honor and justice and the role of the compañeras, just like in the municipality we take turns, we have two consejas [like council or advisor, female], two consejos [male], and one man and one woman assigned to honor and justice. So for example if a compañera has a problem, for example in the case of a rape, she would go talk to the compañera assigned to honor and justice. That compañera from the honor and justice commission then coordinates with the man on the honor and justice commission so that the compañera with the problem doesn’t have to feel uncomfortable with the male compa. That is how the honor and justice commission works.

-*-

(…)

At the zone level, we have another example that is a job done especially by women compañeras. It is a women’s initiative where they created a cafeteria-store, that is, they have a small cafeteria and a small grocery store. They started with a loan of 15 thousand pesos and hatched their idea for this project. The initiative was made by the regional and local leaders in coordination with the Junta, which supported them with tables, dishes, and other useful things for the cafeteria. Various people cooperated to make this happen, but it was these compañeras who had the idea, did the work, and organized it all.

They began with 15 thousand pesos, they have organized their leadership responsibilities, and the compañeras in charge locally take turns at the zone level preparing and selling the food. They reported to us that, in their first business ever, they made a profit of 40 thousand pesos. With this 40 thousand pesos they could pay back the loan that they had taken out, which was 15 thousand pesos, and they had 25 thousand pesos left over.

Then they began to think that they were missing some of the things that they needed to round out the project. The Junta had supported them, as I said, with dishes and tables, but they began to think that with their earnings they wanted to improve things a little, and so they used these profits to better equip themselves. Now they are working like this, they have their leadership, the work rotates among the compañeras, and every year they change the makeup of the leadership. The communities control what is sold there, and they have informed us that they currently have 56,176 pesos in cash according to their last account balance.

All of this is work that we have been doing at the zone level, not with the objective to divide it up among ourselves or to spend these small funds that we are generating, but rather to be prepared for anything that we might need in the zone, for the things that will help us in the struggle.

(…)

We know that in the Tzeltal Jungle zone there are compañeras who are comisariadas (like commissioners), or agentas, how does it work there for these compañeras to be comisariadas and agentas, tell us, share with us how it is. Are there compañeras who function as local authorities? How do they do this? How do these compañeras work? Because there are also compañeros who are comisariados and agentes. What we want to do here is share how it is that we teach ourselves, help ourselves, prepare ourselves. In this case, especially with respect to the compañeras, how do the compañera authorities work in the communities?

What do the compañeras do in their communities as a comisariada or agenta?

The agentas, for example, in my community, are the ones who watch over the community, who keep vigil over certain kinds of problems, things like small interpersonal issues, or problems with animals that cause harm or damages. It is the agente who is responsible for solving these types of problems. They also hold meetings to provide guidance on how to avoid problems with alcohol and drug addiction. These compañeras always participate, in every meeting, providing this guidance to avoid arriving at more serious problems. The comisariadas also hold meetings to discuss land issues—the care of the surrounding lands and the use of agro-chemicals. We planned all of this out as regulations that the comisariadas andagentes administer within the communities to maintain this control.

For the compañeras who have already become agentas, whose job is it to solve problems in the communities, can they already solve the problems themselves, or do they do it with the support of compañeros?

In my community, sometimes the compañeras request the support of a local authority to listen to an issue if they aren’t sure how to participate, so they may ask for counsel. That happens often, but there are times when they [the authorities] aren’t there and the compañeras do it alone. For example, in my community, the agente is a compañera, and so is the substitute agente, and so the two of them have resolved problems themselves. As they have seen it done a few times, they follow this example and create solutions.

(…)

Of the 60 members, are they half compañeras and half compañeros?

Yes compañero, we are half and half, no one is more, no one is less.

(…)

-*-

(To be continued…)

I testify.

From the mountains of Southeastern Mexico.

Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos.

Mexico, February 2013.

—————————

“Tierra y Libertad,” by the group “FUGA.” The song begins with a fragment of the EZLN’s words in the Mexican Congress, demanding compliance with the San Andrés Accords. An indigenous woman gave our Zapatista word there. The group FUGA is comprised of Tania, Leo, Kiko, Oscar and Rafa. The song can be found on the album “Rola la lucha Zapatista.”

——————————-

Mapuche women in resistance against predatory mining companies.

——————————-

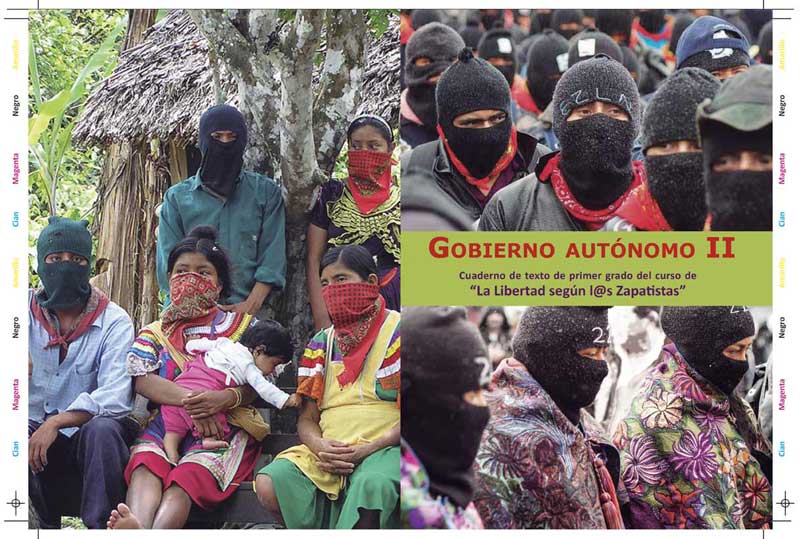

Zapatista women in their cargos in the Junta de Buen Gobierno in La Realidad, Chiapas, in 2008.

Traducción del Kilombo Intergaláctico.

****************************

THEM AND US. VII.- The Smallest Ones. 3.- The Compañeras. The very long road of the zapatistas.

ELLOS Y NOSOTROS.

VII.- L@s más pequeñ@s 3.

3.- Las Compañeras. El muy largo camino de las zapatistas.

Febrero del 2013.

NOTA: A continuación unos fragmentos de la compartición de las mujeres zapatistas, mismos que forman parte del cuaderno de texto “Participación de las mujeres en el gobierno autónomo“. En estos fragmentos, las compañeras hablan de cómo ven su propia historia de lucha como mujeres y, de paso, derrumban algunas de las ideas sexistas, racistas y antizapatistas que, en todo el espectro político, hay sobre las mujeres, sobre las indígenas y sobre las zapatistas.

-*-

-*-

Buenos días a todas, a todos. Mi nombre es Guadalupe, mi pueblo es Galilea de la región Monterrey, como ustedes escucharon, hay regiones que no tienen municipio autónomo, yo vengo de una región donde no hay municipio autónomo. Mi cargo es promotora de educación y represento al Caracol II “Resistencia y rebeldía por la humanidad”, de la zona Altos de Chiapas. Para empezar voy a presentar a ustedes una pequeña introducción para que podamos entrar en el tema.

Sabemos que desde el inicio de la vida las mujeres tenían un papel muy importante en la sociedad, en los pueblos, en las tribus. Las mujeres no vivían como vivimos ahora, eran respetadas, eran las más importantes para la conservación de la familia, eran respetadas porque dan la vida así como nosotros respetamos ahora a la madre tierra que nos da la vida. En ese tiempo la mujer tenía un papel tan importante pero con la historia y con la llegada de la propiedad privada eso se fue cambiando.

La mujer al llegar la propiedad privada fue relegada, pasó a otro plano y llegó lo que llamamos el “patriarcado” con el despojo de sus derechos de las mujeres, con el despojo de la tierra. Entonces fue con la llegada de la propiedad privada que empezaron a mandar los hombres. Sabemos que con esta llegada de la propiedad privada se dieron tres grandes males, que es la explotación de todos, hombres y mujeres, pero más de las mujeres, como mujeres también somos explotadas por este sistema neoliberal. También sabemos que con esto llegó la opresión de los hombres hacia las mujeres por ser mujeres y también sufrimos como mujeres en este tiempo la discriminación por ser indígenas. Entonces tenemos estos tres grandes males, hay otros pero ahorita no estamos hablando de eso.

Nosotros dentro de la organización, con tanta falta de derechos como mujeres, se vio necesario luchar por la igualdad de derechos entre hombres y mujeres, fue así como se dictó nuestra Ley Revolucionaria de Mujeres. Sabemos que nosotros aquí en la Zona Altos tal vez no hemos tenido grandes avances, han sido avances pequeños, son lentos pero vamos avanzando, compañeras y compañeros.

Aquí vamos a decir en la Zona Altos cómo es que hemos avanzado con los diferentes niveles, en las diferentes áreas, en los diferentes lugares donde nos toca trabajar. También vamos a decir cómo en la ley revolucionaria hemos visto, hemos analizado, antes de venir aquí, entre hombres y mujeres analizamos cómo estamos en cada uno de estos puntos de la Ley Revolucionaria de las Mujeres, eso es lo que vamos a decir. Porque es muy importante que en este análisis no sólo participemos las mujeres, también necesitan participar los hombres, para escuchar lo que pensamos, lo que decimos. Porque si estamos hablando de una lucha revolucionaria, una lucha revolucionaria no la hacemos sólo los hombres ni sólo las mujeres, es tarea de todos, es tarea del pueblo y como pueblo habemos niños, niñas, hombres, mujeres, jóvenes, jóvenas, adultos, adultas, ancianos y ancianas. Todos tenemos un lugar en esta lucha y por eso todos debemos participar en este análisis y en las tareas que tenemos pendientes.

(…)

-*-

(…)

Compañeros, compañeras, mi nombre es Eloísa, del pueblo Alemania, municipio San Pedro Michoacán, fui miembro de la Junta de Buen Gobierno, del Caracol I “Madre de los caracoles. Mar de nuestros sueños”. Nos toca hablar un poco sobre el tema de las compañeras y a mí me tocó hablar un poco cómo es que era la participación antes del 94 de las compañeras y un poco cómo fuimos avanzando después del 94.

Así como platicamos en nuestra zona, que de por sí desde un principio nosotras como compañeras no participábamos, nuestras compañeras de más antes no teníamos esa idea de que nosotras como compañeras podemos participar. Teníamos ese pensamiento o esa idea que nosotras las mujeres sólo servimos para el hogar o cuidar los hijos, hacer la comida; tal vez será por la misma ignorancia del capitalismo que eso es lo que teníamos en la cabeza. Pero también nosotras como mujeres sentíamos ese temor de no poder hacer cosas fuera del hogar, así como también no teníamos ese espacio de parte de los compañeros.

Al igual no teníamos esa libertad de participar, de hablar, como que se pensaba que los hombres eran más que nosotros. Cuando estamos bajo dominio de nuestros padres, nuestros padres no nos daban esa libertad de salir pues era mucho el machismo que se vivía antes. Tal vez los compañeros no es porque ellos lo querían hacer sino porque tenían la idea que el mismo capitalismo o el mismo sistema nos lo penetró en la cabeza. También porque el compañero no está acostumbrado a hacer oficios dentro del hogar, a cuidar los hijos, a lavar la ropa, hacer la comida y eso es lo que le dificulta al compañero hacer los oficios dentro del hogar pues le hace difícil cuidar los hijos para que la compañera pueda salir a hacer su trabajo.

Como dije antes, las compañeras que vivimos bajo dominio de nuestros padres o vivimos todavía con nuestros padres, como tenemos un respeto que cuando estamos con nuestros padres, nuestros padres dicen si podemos hacer el trabajo, pues nos vamos a donde queremos hacer el trabajo. Pero si nuestros padres, a veces que nos dicen no vas a ir, es que a veces le respetamos, también a veces que tenemos en la cabeza que le respetamos a nuestros padres. Entonces hay veces que nuestros papás no nos saca, también ha pasado que piensan que al sacarnos fuera de nuestras casas como hijas no vamos al trabajo que nos corresponde sino que vamos a hacer otras cosas y después involucramos a los papás en problemas y ya los papás se ocupan a ese espacio a arreglar nuestros diferentes problemas que tenemos como mujeres. A veces también eso es la idea de nuestros padres o de los esposos, los que ya son parejas, o sea que eso también a veces tienen en la idea los compañeros.

(…)

-*-

Compañeros y compañeras, muy buenas tardes a todos ustedes que hoy aquí están presentes. Mi nombre es Andrea, mi pueblo es San Manuel, mi municipio es Francisco Gómez del Caracol III “La Garrucha”. Venimos representando nosotros como compañeras de la zona de Garrucha, lo que alcanzamos a expresarnos pues no traemos tantas palabras, casi allá la mayoría hablan en tzeltal.

Voy a empezar primero con lo que habíamos sabido que antes de 94 habían sufrido mucho las compañeras. Había humillaciones, maltratos, violaciones, pero al gobierno no le importaba eso, su trabajo es nomás destruirnos como mujeres. No le importaba si es que hay una mujer que se enfermaba o pides ayuda o auxilio, eso no le importa.

Pero nosotras como mujeres, ya ahora, ya no podemos dejarnos a eso, tenemos que seguir adelante. En esos tiempos hemos sufrido, así es que han comentado las compañeras. En esos tiempos que dije que había muchas humillaciones, lo que hacía el mal gobierno y también los finqueros, ¿qué es lo que hacían en ese tiempo? Es que a las compañeras no las tomaban en cuenta.

¿Esos finqueros qué hacían? Los tenían en mozo a los compañeros, las compañeras se levantaban muy temprano a trabajar y de esa forma todavía las pobres mujeres seguían trabajando juntamente con los hombres. Había mucha esclavitud, pero compañeros, ahora ya no queremos eso, así es que ya apareció nuestra participación como compañeras. En ese tiempo no había participación, nos tenían así como ciegos, sin poder hablar. Pero lo que queremos ahorita es que ya funcione nuestra autonomía, queremos que ya participemos nosotras como mujeres, que ya no nos dejemos atrás. Seguiremos adelante para que vea el mal gobierno que ya no nos dejamos explotar como lo hizo con nuestros antepasados. Ya no queremos.

Ya de ahí hasta el año de 94 se supo que ya había nuestra ley de mujeres. Qué bueno, compañeros, que ya hubo eso, que ya hemos participado. Desde ese año ya habían salido manifestaciones, ya se ha visto que ya han salido las compañeras, por ejemplo en la Consulta Nacional salieron las mujeres también, participaron. Yo también presenté en ese tiempo, yo tenía 14 años y presenté la Consulta Nacional. De esa forma, yo no sé ni participar ni hablar, pero sí hasta donde pude lo hice, compañeros.

Ya lucharon, ya demostraron, ya el gobierno se dio cuenta que también las mujeres ya no se dejaban, seguían. Ya ahora, que ya dije que ya queremos que funcione nuestra autonomía, y apareció nuestros derechos como mujer, lo que vamos a hacer ahora es ya construir, hacer el trabajo, así como dicen que ya es nuestra obligación seguir adelante.

Entonces nosotras que ya ahora estamos aquí presentes, no sé si alguna compañera que me sucede, una pregunta, si saben quién fue que hizo esa ley revolucionaria. Si alguien lo quiere responder lo puede responder, porque alguien fue que luchó por eso y alguien fue que defendió por nosotras. ¿Quién fue que luchó por nosotras, compañeras? La Comandanta Ramona, fue que hizo ese esfuerzo para nosotras. Ella no sabía leer ni escribir, ni hablar en castilla ¿Y por qué nosotras entonces, compañeras, no hacemos ese esfuerzo? Es un ejemplo esa compañera que ya hizo el esfuerzo. Ya es ella el ejemplo que vamos a seguir más adelante para hacer más trabajos, demostrar qué es lo que sabemos en nuestra organización.

-*-

Me toca representar a las compañeras que van a participar en tema de mujeres, que son 5 compañeras que van a participar. Buenas tardes a todos. Mi nombre es Claudia. y vengo del Caracol IV de Morelia. Soy base apoyo del pueblo Alemania, región Independencia, municipio autónomo 17 de Noviembre. Voy a leer un poco, antes de entrar con nuestros subtemas, traigo una introducción. Voy a leer el escrito porque si digo así nomás, ya estando aquí enfrente, se me va olvidar lo que voy a decir.

Mucho más antes sufríamos por el maltrato y la discriminación, la desigualdad en la casa, en la comunidad. Siempre sufríamos y nos decían que éramos un objeto, que no servimos nada, porque así nos enseñaron nuestras abuelas. Sólo nos enseñaron a trabajar en la casa, en el campo, cuidar el niño, los animales y servir el esposo.

Nunca tuvimos la oportunidad de ir a la escuela, por eso no sabemos leer ni escribir, mucho menos hablar en castilla. Nos decían que una mujer no tiene derecho de participar ni reclamar. No sabíamos defendernos ni conocíamos qué es un derecho. Así fueron educadas nuestras abuelas por sus patrones que eran los rancheros.

Algunas de nosotras ahora todavía tenemos esa idea de trabajar sólo en la casa porque así vino encadenando este sufrimiento hasta ahora donde estamos. Pero después de diciembre de 1994 se formaron los municipios autónomos, es ahí que empezamos a participar, a conocer cómo hacer los trabajos, gracias a nuestra organización que nos dio un espacio de participación como compañeras, pero también gracias a nuestros compañeros, a nuestros papás que ya entendieron que sí tenemos derecho a hacer los trabajos.

(…)

-*-

Compañera Ana. Nuevamente nos toca el turno otra vez a la Zona Norte, ya están acá los participantes que van a hablar de los temas que se analizó allá en nuestro caracol. Voy a empezar con una introducción.

Hace muchos años atrás existía la igualdad entre hombres y mujeres porque no había uno que era más importante que el otro. Poco a poco empezó la desigualdad con la división del trabajo, cuando los hombres son los que salían al campo a cultivar para sus alimentos, salían de cacería para completar la alimentación en las familias y las mujeres se quedaban en la casa para dedicar a los trabajos domésticos, así como también el hilado, el tejido de la ropa y en la elaboración de utensilios de cocina, como las ollas, vasos, platos de barro. Más después surgió otra división del trabajo en aquellos que empezaron a dedicarse a la ganadería. El ganado empezó a servir en forma de dinero ya que lo utilizaban para intercambiar sus productos. Con el tiempo esta actividad se convirtió como el más importante, más aún cuando empezó a surgir la burguesía que se dedicaban a comprar y vender para acumular ganancias. Todo este trabajo son los hombres quienes lo dedicaban, por eso son los hombres que mandan en la familia, porque él solo conseguía para los gastos de la familia y el trabajo de las mujeres no era reconocido como importante, por eso se quedaron como las menos, débiles, incapaces de hacer un trabajo.

Así era la costumbre, el modo de vida que trajeron los españoles cuando vinieron a conquistar nuestros pueblos, como ya dijimos anteriormente, que son los frailes quienes nos educaban e instruían en sus costumbres y conocimientos. Desde ahí nos enseñaron que la mujer tenía que servirle a los hombres y hacerle caso en todo momento cuando da órdenes, y que las mujeres deben cubrir su cabeza con un velo cuando van a la iglesia y que no tiene que fijar su mirada por cualquier lado, tiene que estar agachadito su cabeza. Se consideraba que las mujeres son los que hacían pecar a los hombres por eso la iglesia no les permitía que las mujeres vayan a la escuela ni mucho menos ocupar cargos.

Nosotros los pueblos indígenas lo agarramos como una cultura la forma como los españoles trataban a sus mujeres, por esa razón en las comunidades empezó a surgir la desigualdad entre hombres y mujeres que sigue hasta ahora, como estos ejemplos:

Las mujeres no les permiten ir a la escuela y si una muchacha sale a estudiar era mal vista por la gente de las comunidades. A las niñas no les dejaban jugar con los niños ni tocarles sus juguetes. El único trabajo que debe hacer las mujeres es en la cocina y a criar hijos. Las muchachas solteras no tenían la libertad de salir ni de pasear en la comunidad ni en la ciudad, tenían que estar encerradas en su casa, y cuando se casaban eran cambiadas por el alcohol y otras mercancías, sin que la mujer dé su palabra si está de acuerdo o no, porque no tenía el derecho de elegir a su pareja. Cuando ya están casadas no podían salir a solas ni hablar con otras personas, más si son hombres. Existía el maltrato de las mujeres por sus maridos y nadie aplicaba justicia, estos maltratos más los realizaban los hombres que toman trago. Así tenían que vivir toda su vida con sufrimiento y abuso.

Otra de las cosas que hacían las mamás era instruir a sus hijas en que tienen que servirle la comida a sus hermanos, para que más adelante pueda vivir bien con su esposo y no recibir maltrato, porque se cree que una de las razones del maltrato de la mujer es que no aprendieron a servirle a su marido y hacerle caso en todo lo que el hombre indique.

Pero también nuestros abuelos y abuelas tenían sus costumbres buenas que siguen practicando hasta ahora, por eso no hay mucha preocupación cuando hay enfermedades, porque conocían las plantas medicinales y sabían mucho de cómo cuidar la salud. No se preocupaban por la falta de dinero porque todo lo que necesitaban para la alimentación ellos lo cultivaban, por eso las mujeres de antes eran fuertes, trabajadoras, porque elaboraban su propia ropa, calhidra, aunque no conocían su derecho pero pudieron salir adelante.

(…)

-*-

(Continuará…)

Doy fe.

Desde las montañas del Sureste Mexicano.

Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos.

México, Febrero del 2013.

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Ve y escucha los videos que acompañan este texto:

Y ya que de mujeres se trata, aquí Violeta Parra cantando “Arauco tiene una pena”. 50 años después de esta voz, el Pueblo Mapuche sigue resistiendo y transformando esa pena en rabia.

———————————————————————————————

Audios e imágenes del encuentro “La Comandanta Ramona y las zapatistas”, celebrado en el tierras zapatistas, en diciembre del 2007. En una parte, nuestra compañera Comandanta Susana recuerda a la Comandanta Ramona, fallecida en enero del 2006.

——————————————————————————-

Mensaje de las compañeras zapatistas a las compañeras de todo el mundo, en diciembre del 2006. Minuto 2:22 dice la compañera “No necesitamos a un profesionista a que nos venga a decir cómo debemos vivir”.

————————————————————————————-