(Español) Campaña ¡Va por Kuy! Acto Político Cultural este domingo 21 de Abril

En el marco de la denuncia de la represión del 1 de dic 2012

Acto Político cultural

En Solidaridad con Kuy

Domingo 21 de abril,

explanada del Palacio de Bellas Artes

de 12 a 22 horas

Danza, teatro, canto, música, poesía, propuesta política, comercio justo, y….bailongo

CONVOCAN:

COLECTIVOS, ORGANIZACIONES, GRUPOS, INDIVIDUOS ADHERENTES A LA SEXTA DSL Y A LA RED CONTRA LA REPRESION Y POR LA SOLIDARIDAD.

More actions demanding Patishtan´s freedom and demo in El Bosque

A la Opinión Pública

A los medios de comunicación estatal, nacional e internacional

A medios alternativos

A los adherentes a la sexta

A las organizaciones independicntes

A los defensores de derechos humanos ONG’S

Preso político de la voz del amate adherente a la sexta recluido en el penal No. 5, San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas.

Hoy viernes 12 de abril terminó nuestro ayuno de la segunda jornada que tuvo y tendrá un fin de exigir la justicia verdadera como también el día sábado y domingo 13 y 14 del presente nuevamente estaremos protestando nuestras libertades con una marcha silencio dentro del penal.

Por lo tanto sigo exigiendo a las autoridades del 1er tribunal Colegiado del Vigésimo Circuito de Chiapas a que tomen en cuenta mi Reconocimiento de Inocencia y que resuelvan mi caso y sea otorgado mi Libertad Inmediata e Incondicional.

Así también exijo al Gobierno Estatal Manuel Velazco Coello a que otorgue la libertad de todos mis compañeros solidarios, la voz del amate que me acompañen de acción de exigir libertad conjunta, porque de igual manera son acusados falsamente que a través de las torturas y mutilaciones se autoculpara de los delitos, prefabricadas de las mismas autoridades.

Por último invito a la sociedad civil a las organizaciones independientes Estatales, Nacionales, e Internacionales a seguir exigiendo nuestras libertades ante el gobierno porque no es justo que no tienen secuestrados por parte del mal sistema.

¡vivir o morir por la verdad y la justicia!

FRATERNALMENTE

Preso Político de la Voz del Amate

Alberto Pathistan Gómez

Penal No. 5 San Cristobal de Las Casas Chiapas; a 12 de abril del año 2013.

We are wind – Resistance in the Istmo against the Wind Farm project of Mareñas Renovables

Este documental muestra el conflicto generado por la intención de la instalación del “Parque eólico San Dionisio del Mar” en el Istmo de Tehuantepec enfocandose en las realidades y opiniones de los habitantes de la región. Dando la palabra a aquellos que no aparacen en los medios masivos. A parte muestra la lógica de los proyectos eolicos en una visión más global explicando brevemente el discurso de la energía verde y el supuesto “desarollo limpio”.

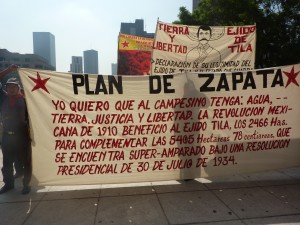

Report from Tila about the suspension of the discussion in the Supreme Court

En este audio escucharemos la palabra de los ch´oles de Tila ante la suspensión de la discusión en la Suprema Corte de Justicia y de la intención de promover la indemnización de sus 130 hectáreas. También desmiente al periódico Cuarto Poder y narra la situación que se vive actualmente en el ejido.

(Descarga aquí)Public statement by the people displaced from Banavil, Tenejapa

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=nNdfIBylryo

A 27 de marzo de 2013, San Cristobal de Las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico.

A la Otra Campaña

A la Sexta Declaracion de la Selva Lancandona.

Al Congreso Nacional Indigena

A los Centros de Derechos Humanos Honestos e Independientes

A los medios de Comunicacion

A la sociedad Civil Nacional e Internacional

A los pueblos creyentes

A la opinión publica.

Hermanas y hermanos esta es nuestra palabra sencilla y humilde.

Nosotros hombres, mujeres y niñas desplazados del paraje Banavil, municipio de Tenejapa, Chiapas, Mexico, somo simpatizantes del EZLN fuimos desplazados 13 personas desde el 04 de diciembre de 2011, durante este tiempo hasta la fecha estamos exigiendo justicia y que ejecuten la orden de aprension contra las 11 personas que son las que estan acusados de homicidio de Alonso Lopez Luna y de las lesiones de Lorenzo Lopez Giron hasta el momento las autoridades no lo quieren ejecutar las ordenes de aprension.

Nosotros los desplazados nos hemos enfermado mucho, pero mas las mujeres y las niñas se enferman de tos, gripa y calentura y no han recibido atencion medica porque no tenemos dinero para comprar medicamentos y tampoco el gobierno nos da atencion medica, no tenemos ningún apoyo. Y nuestro alimento no nos al cansa para comer no tenemos servicio de agua cuando encontramos agua lo guardamos en botes, estamos tristes por nuestra situación porque además no encontramos trabajo, También hace poco nos enteramos que nuestras tierras, que esta en el ejido de Santa Rosa en el mismo municipio de aproximadamente cinco hectareas y media, los priistas lo invadieron y los tienen posesionados una parte los estan parcelando para repartirse entre los agresores priistas, el que ordena estas posesiones son estos lideres. Agustin Mendez Luna, Pedro Mendez Lopez, Alonso Lopez Ramirez y Agustin Guzman Mendez. Una parte de nuestras tierras lo vendieron estos agresores hasta la fecha nos sabemos con quienes lo vendieron pero si sabemos que son dos hectareas tres cuartos que ya estan vendidas y que el comprador ya esta haciendo su milpa en nuestras tierras.

El 8 de marzo, tuvimos una reunion con el Juez Propietario Joaquin Intzin Lopez en la fiscalia indigena junto con el Licenciado Lesther Gutierrez Duran, para pedir que nos den seguridad y entrar a sacar nuestras cosas como, maiz, chicharo, avas, ropa, machete, azadon , hacha, son cosas que necesitamos para sobrevivir. Pero el juez dijo que no podia decidir, que solo esta trabajando por su sueldo y que recibe ordenes del presidente municipal de Tenejapa que se llama Esteban Guzman Jimenez, ese dia nos dijo que no se queria meter en este problema, pero que se ha reunido con el grupo priista agresor. Por telefono le dijo al licenciado Lester que ya no hay maiz en nuestra casa, pero Lester es testigo que si quedo dejamos maiz dentro de nuestras casa. En varias ocasiones hemos acudido al mesa seis que esta en la fiscalia indigena para solicitar copias de la averiguacion previa pero no nos quieren dar, siempre cuando vamos nos salen preguntando para que nos va servir las copias, que si somos licenciados para checar y ver, que porque nosotros no tenemos derecho de pedir las copias, ni siquiera nos dan información de como se encuentran las averiguaciones previas tampoco vemos avances de parte de la mesa seis de la fiscalia indigena, solo nos dicen que estan trabajando mandando escritos, y cuando pedimos que nos de copias nos dicen que no. Que tienen firmado un acta de acuerdo el fiscal, el director y el sub director de averiguaciones previas de la fiscalia indigena para que no nos den ningun documento. Sabemos que Pedro Mendez Lopez y Manuel Mendez Lopez trabajan en la presidencia municipal de Tenejapa, estas dos personas son los que mataron a mi padre Alonso Lopez Luna hasta fecha sigue desaparecido y estas dos personas tienen orden de aprension y no la ejecutan las autoridades. El dia lunes 18 de marzo de este año los agresores priistas amenazaron a Francisco Santiz Lopez en devolverlo a la carcel por cien años mas y que también a Lorenzo Lopez Giron. En el paraje de banavil estan reuniendo cinco mil pesos por cada persona, para venir a comprar a los de la fiscalia para que nos busquen mas delitos, sabemos que en el ejido mercedez juntaron 25 mil pesos y Alonso Lopez Mendez vino a dejar en el paraje banavil para comprar a los de la fiscalía indígena.

Por ultimo denunciamos estos hechos y exigimos al señor gobernador Manuel Velasco Coello y el señor Enrique Peña Nieto, que resuelva nuestro problema, exigimos nuestras cosas, nuestras tierras y casas.

¡¡CASTIGO POR LOS ASESINOS!!

¡¡PRESENTACION EN VIDA DE MI PADRE ALONSO LOPEZ LUNA!!

ATENTAMENTE LOS DESPLAZADOS DE BANAVIL

LORENZO LOPEZ GIRON

MIGUEL LOPEZ GIRON

PETRONA LOPEZ GIRON

ANITA LOPEZ GIRON

ANTONIA GIRON LOPEZ

MARIA MENDEZ LOPEZ

PETRONA MENDEZ LOPEZ