Migrant caravan on the move through Pijijiapan and Tonalá, Chiapas

It is early morning. It is not yet 2 a.m. and an almost full moon illuminates the streets of Mapastepec. The small city is sleeping, but in the central plaza, on the patio of the church and in the surrounding streets, some groups are already awakening, and they begin to organize their few belongings. An hour later, there is a feverish activity and many have already started their journey. They organize into groups of 10, 20, or 30 people. The small children are carried in the arms of their mothers or fathers, but the majority, despite their sleepiness and exhaustion, walk by themselves.

When they get to the highway, they turn in direction of Pijijiapan, with the hope that someone will stop and give them a ride. Many vehicles do, particularly after 6 a.m. when the trucks and minibuses begin to circulate. They progress a few kilometers and when they approach an immigration, police, or army checkpoint, the drivers stop and the migrants get off. Many drivers fear having problems with the authorities. The migrants cross the checkpoints by foot without problems—in fact, at many checkpoints, such as military ones, there is no personnel—and then the migrants wait for another driver to pick them up further ahead.

(Descarga aquí)

Several hours later, the central plaza of Pijijiapan and many of the surrounding blocks overflow with people. Some decide to continue on to avoid overcrowding. In Tonalá, there are between 400 and 500 people and in Arriaga, between 200 and 300.

Solidarity

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the migrant caravan passing through Chiapas is the solidarity among locals. In the community of Nuevo Urbina, local women met the night before to discuss the caravan. Shortly after the earthquake last year, and in response to government inaction and lies, the community organized itself to rebuild their houses with the support of the BioreconstruyeMX Chiapas collective. This process has solidified community ties. The collective began a project to build sustainable stoves with the intention of teaching locals how to build them so that everyone could have one at their home. The first one was built in the community house (casa del pueblo), where the community also installed a water purifier for the community.

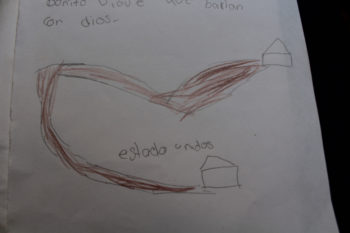

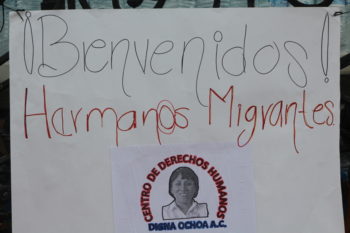

Inspired by doña Lázara, a very respected woman in the community, the women decided to support the migrants with water, shoes, and food. The next day, there were already 15 women gathered at 6 a.m. at the community house. Seven hours later, they had prepared 5,000 tamales that they took to Pijijiapan’s town center in the evening, along with jugs of water and other items donated by the community and members of civil organizations from Tonalá. The children of the community also participated, writing and illustrating letters for migrant children and creating a large banner with a message for migrant children that read, “Your hearts are brave. Don’t give up.” They hung it on the bridge on the highway.

(Descarga aquí)At a school in Pijijiapan, the principal suggested to the children’s parents that they close the school for the day so that they could use the school to provide a place for the migrants to sleep. The families not only agreed; they also donated diapers, baby food, medicine, water, and food. The principal and a group of volunteers distributed the donations throughout the day and night.

In the community of Hermenegildo Galeana, close to Pijijiapan, the community donated water and tamales. By 5 a.m. they were standing on the side of the highway to help migrants, not just with water and food, but also with words of support. This, despite the fact that they had worries of their own and some level of criticism regarding the situation. In Mexico there is a lot of poverty and there are no jobs, they said. What will happen if the U.S. government does not allow the migrants to cross the northern border? “This will weigh down on us.” In addition, they fear the reaction of the U.S., which could make it even more difficult for Mexicans to obtain visas. Despite these concerns, they support the migrants. We are all poor, they explained… we help each other.

Murky Interests

It is also surprising to see the Mexican government’s change of position regarding the caravan. In the beginning, Peña Nieto announced that he would not allow the migrants to enter the country in an “unregulated way, and even less, in a violent way.” At the border, more than 300 agents of the Federal Police tried to stop the migrants from crossing, making use of fences, riot gear, and tear gas bombs. Amidst the chaos, one baby died from an impact of a bomb fired by police, according to an interviewee of RZ who witnessed the event. There has not yet been an official statement regarding this death. The government’s position also had an impact on the population of the city of Tapachula, where a government discourse of fear led people to close their doors.

Despite this, starting at Huixtla, there was a noticeable change. The municipal governments have mobilized to offer water, food, and health services, and the discourse has shifted to one of solidarity and support for “our Central American brothers and sisters.” The help has been greatly appreciated, yet insufficient. Likewise, there is a noticeable and increasing tendency for the support to be self-promotional, with self-aggrandizing speeches and events that appear to be more of a decontextualized party than a genuine effort to help. The blaring music in Tonalá and Pijijiapan, which came after speeches in the case of the latter, did not allow the thousands of exhausted people who were crowded on the plaza to rest.

At the same time, some changes made to the route taken by the migrants are difficult to explain. At Huixtla, it was decided to avoid the route to San Cristóbal de Las Casas and Tuxtla, and instead to continue along the coast towards Arriaga. Last night, at Pijijiapan, Irineo Mujica, from Pueblos sin Fronteras, proposed that they now continue through the route of Arriaga, Juchitán, Tehuantepec, Oaxaca and Puebla, before arriving to Mexico City. It was also proposed to seek a dialogue with the federal government to promote the approval in Congress and Senate of legislation that would eliminate visas for Central Americans and that the Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados (COMAR) modify their processes to guarantee a response to asylum requests within 15 days instead of the current 45 to 90 days. In a later interview, Mujica expressed hope with the change of government. Despite this, some migrants interviewed were perplexed by the proposals: their intention is to reach the U.S. border with the hope of being able to cross and support their families, not to negotiate political changes in Mexico.

In this context, the federal government’s position has changed completely. After participating on a panel on migration at the Bloomberg Global Business Forum in New York, Peña Nieto, along with the President of the Swiss Confederation Alain Berset, announced their signing of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, which would be put into effect during the Intergovernmental Conference of the United Nations in Marrakech this upcoming December 10-11. Peña Nieto asserted that “international migration is one of the most pressing international challenges and, at the same time, an enormous opportunity to promote development,” emphasizing its “potential to promote economic and social development worldwide.”

One should wonder what caused this change in position and what does it have to do with the relationship with neighboring United States and its president, Donald Trump, who continues to use the caravan to further his own political ends. U.S. mid-term federal elections will take place on November 6, where the control of the Congress is at stake. According to surveys, there is a strong possibility of the elections resulting in the opposing party, the Democrats, winning a majority. Using an increasingly xenophobic discourse, Trump has declared that the caravan represents a threat to national security for the country and has made other absurd affirmations, such as that the caravan contains infiltrated terrorists of the Islamic State and members of the Mara Salvatrucha gang.

Meanwhile, down below…

While the powers at the top are fighting over political loot, down below, on the streets and highways of the state of Chiapas, under a scorching sun, the migrants continue to walk. Their stories constitute a very different panorama from what can be seen from the top. A man from Honduras, who traveled with his 10-year-old daughter, lamented that he had to leave behind his pregnant wife in Honduras. She will give birth in two weeks. “I will probably not see him be born,” he said. Yet, it is necessary to forge ahead, for the sake of the family.

(Descarga aquí)

It is family that, according to the testimonies collected, motivate the majority of the migrants. Various people say that they have been tempted to go back. The exhaustion, uncertainty, heat, thirst, and risks, especially for kids, is a lot to contend with. But for the family, it is necessary to continue. “To walk and to walk as far as we can go. That is our struggle.” “It is like a mountain… the path leads up and I plan to continue.” They know it will be difficult to cross the border, that only a few make it, but they plan to do everything in their power to accomplish it. For many, it is the economic situation that motivates them: unemployment or exploitative work conditions that make it impossible to survive. For others, it is about fleeing violence, fleeing a reality where death lurks at every moment. For Karina (a pseudonym), who travels with her husband and her 3-year-old son, their journey is about life… the life of their son who is sick and who can’t get adequate attention or medication in Honduras.

Yet perhaps the most eloquent interview is the one we couldn’t do. When we asked one young man if he could tell us why he was travelling, he said, thoughtfully: “No… no, I can’t… no… it would make me remember things that I am trying to forget.” And we left him with a lost gaze, staring into emptiness or maybe reliving a scene that, despite his efforts, insists on coming back to him.

Testimonies:

me da animo y esperanza al ver y escuchar este apoyo y solidaridad para la gente de la caravana. Ojalá que todos los hondureños vengan a mi ciudad Seattle. Bienvenidos sean!

Comment by Kathleen Skeels — Oct-28-2018 @ 21:10

Thank you for this important and heart-rending story. I will share it with friends and family. The world should know the truth.

Comment by Dan Keller — Oct-30-2018 @ 12:10