desaparecidos

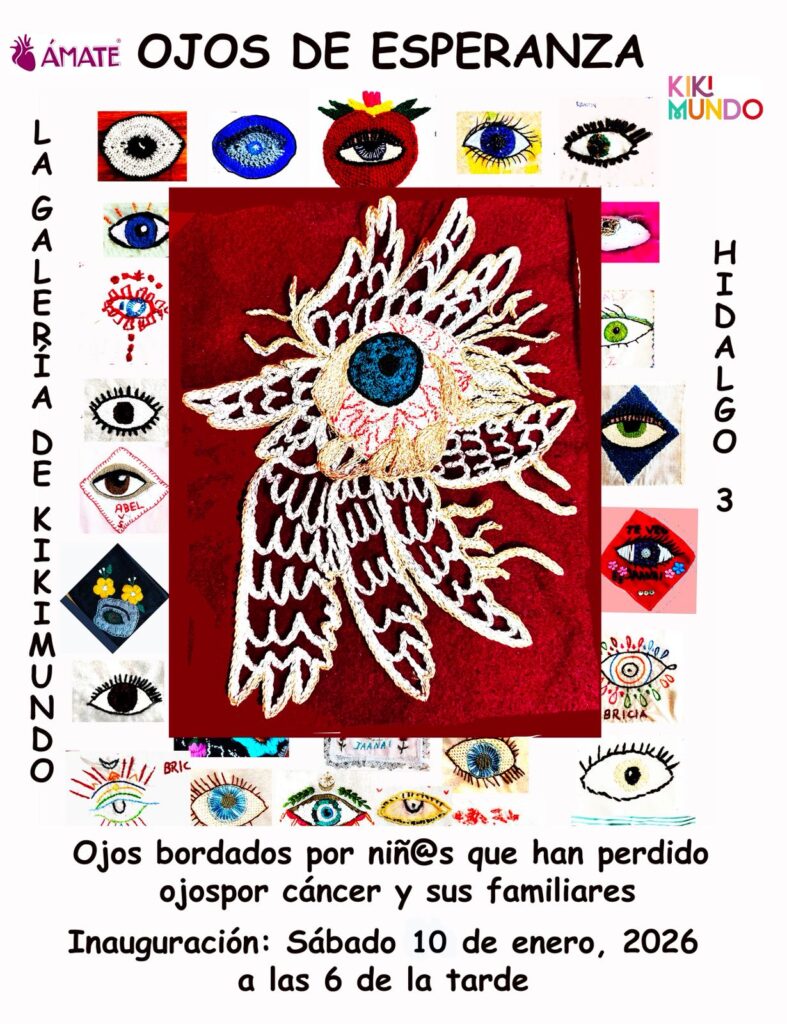

“Ojos de esperanza”: Exposición en solidaridad con las Madres Buscadoras

En México hay más de 100 mil personas desaparecidas y 115 mil no localizadas. El gobierno y sus dependencias han fallado gravemente en la búsqueda y en el rescate de personas desaparecidas. Por ello, hoy existen entre 100 y 120 colectivos de familiares que buscan a sus seres queridos por cuenta propia. Son decenas de miles de padres, hermanas, hermanos y, en su mayoría, madres: LAS MADRES BUSCADORAS, mujeres que arriesgan sus vidas para encontrar rastros de sus hijas e hijos desaparecidos. La crisis en México es profunda y dolorosa. Frente a la apatía y la inacción oficial, LAS MADRES BUSCADORAS HAN ENTRADO EN ACCIÓN. No cuentan con protección institucional; han sido hostigadas, agredidas y algunas han sufrido ataques mortales.

Este sábado 10 de enero, en San Cristóbal de Las Casas, se presenta la exposición Ojos de esperanza, con ojos bordados por niños que han perdido ojos por cáncer y sus familiares.

Galería de Kikimundo

Calle Hidalgo 3

San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas

Sábado, 10 de enero de 2026 – 6 pm

Con nuestros ojos bordados queremos decirles: Las vemos. Los vemos. No están solas. Somos solidari@s. Todo lo recaudado de estos ojos –bordados por personas de muchos lados de la republica y del extranjero– beneficiarán directamente a Madres Buscadoras.

En la exposición se espera también la participación de la ceramista Erika del Río, con la muestra La vista gorda, creada especialmente para Ojos de esperanza:

LA VISTA GORDA. Nunca he perdido a alguien de esta manera, he logrado ver su cuerpo antes de despedirme y aceptar que no volveré a sentir su calidez. Una urna funeraria que lastimosamente no contiene nada ni puede. Perforada, silenciada en el cierre de carpetas ocultas y olvidadas. Ante la indiferencia e incompetencia de las autoridades, la impunidad y los intereses políticos que pisan la dignidad humana ante la materia inexistente, intangible del cuerpo. La gorda… la vista gorda ante tantos hechos, ante el peso gigantesco que se siente, con las miradas que buscan sin cansancio contra las que esquivan responsabilidad. Ciudadanos que ven la verdad y se arriesgan para hacer justicia. La gorda situación que parece no ser vista y pasar inadvertida. Ignorada. Declaro: Yo te veo –como mujer, como ser humano que ha vivido con la muerte de la mano, como hija, como hermana–. Siento, el coraje de la injusticia de la mentira, el dolor de una memoria, de una herida que no logra sanar, la herida que sigue abierta. En la búsqueda sin norte ni sur, en la ubicación desconocida, en el sonido del silencio y en el estruendo de las balas que se ven por gravedad en las cenizas. Enciende una luz en el camino de la desesperación, el desconsuelo, la angustia y la tristeza de no saber dónde, cuándo, cómo, por qué. Una luz para resignificarse ante la duda, para la fuerza y la valentía. Un abrazo en soledad y al interior de cada familiar y ser amado que se ha quedado incompleto sin autorización, sin permiso, sin justificación.

—Erika del Rio

Antonio González Méndez Case before the IACHR: One Year After the Ruling, State Actions Lack Diligence and Effectiveness

San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico

December 12, 2025

Press Release No. 11

Antonio González Méndez Case before the IACHR: One Year After the Historic Ruling

Neither the investigations nor the search efforts have been diligent or effective

The enforcement of the ruling has not been properly prioritized by the Mexican State.

On December 12, 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) notified its ruling condemning the Mexican State for the forced disappearance of Antonio González Méndez, an EZLN Support Base, who was disappeared on January 18, 1999, in the municipality of Sabanilla, Chiapas, by members of the paramilitary group “Organization for Development, Peace, and Justice” in the context of the counterinsurgency violence triggered by the implementation of the Chiapas Campaign Plan 94.

The ruling reaffirmed that forced disappearances committed within the context of the Internal Armed Conflict, which began on January 1, 1994, are not subject to statute of limitations and obliges the Mexican State to be held accountable. This represents a historic precedent for other victims of severe human rights violations.

As the 27th anniversary of his disappearance approaches, the Mexican State continues with mere administrative procedures, superficial efforts aimed at conducting an unfruitful investigation. Both the search and the investigations have not been diligent or effective in locating Antonio González Méndez. What the State Prosecutor’s Office considers the hypothesis of his disappearance at the hands of a paramilitary group reveals a case that remains unresolved. The IACHR ruling, which takes this hypothesis as a fact and holds the Mexican State responsible for supporting paramilitary groups in the region, continues to be disregarded, raising doubts about the seriousness of the State’s commitment. It is essential to fully clarify what happened and to identify, prosecute, and, if applicable, sanction all intellectual and material authors of this crime against humanity.

The obligation of the Mexican government must not be reduced to symbolic actions or mere paperwork; the investigation should include clear lines of action to identify those responsible, both material and intellectual, and prosecute them in accordance with human rights standards.

The persistent impunity and partial non-compliance with the IACHR ruling highlight the enormous challenges in translating an international ruling into real and tangible changes. The central issue remains the location of Antonio González Méndez and the carrying out of a professional, scientific, and independent investigation that guarantees justice and truth. This case not only reflects the pending debt to his family but also starkly exposes the structural crisis of human rights, justice, and impunity that Mexico is facing.

The Mexican State is obligated to implement the structural reforms ordered by the IACHR: a national and up-to-date registry of missing persons, effective prevention programs, specialized training to investigate state crimes, and public policies that recognize the collective rights of indigenous peoples through a comprehensive human rights approach. It is not just about complying with a ruling, but about transforming institutions so that these violations are never repeated.

At Frayba, alongside the family of Antonio González Méndez, we will continue to insist that justice be fully served. We will persist in the search for the truth and the demand for justice, because only in this way can we honor Antonio’s memory and pave the way for a Mexico where impunity is the exception, not the rule. This struggle is also the struggle for all the disappeared persons and for the dignity of the peoples who demand truth, justice, and non-repetition.