Listen here:

[podcast]https://radiozapatista.org/Audios/pensamiento/homenaje_sup-galeano2.mp3[/podcast]

May 2, 2015

Compañeros and compañeras of the Zapatista Army for National Liberation:

Compañeroas, compañeras, compañeros of the Sixth:

Visitors:

It is my turn to talk about our compañero, the Zapatista teacher Galeano.

To talk about him so that he can live on in our words.

To talk to you about him so that you might understand our rage.

We say “the Zapatista teacher Galeano” because this was the cargo [job or responsibility] that our compañero held when he was assassinated.

For us, Zapatistas, the compañero teacher Galeano epitomizes an entire anonymous generation within Zapatismo. Anonymous to those on the outside, but for us, the fundamental protagonist in the uprising and in these more than 20 years of rebellion and resistance.

It is a generation that, as youth, was part of the so-called social organizations and therefore knew of the corruption and deceitfulness that nurtured their leaders. This generation prepared itself in secrecy, rose up in arms against the supreme government, resisted the betrayals and persecutions alongside us and guided the resistance of the today’s generation that now takes on cargos in the indigenous communities.

A violent, absurd, ruthless, cruel, and unjust death came to him while he held the cargo of teacher.

A bit later and it would have been in the cargo of autonomous authority.

A bit earlier and it would have been as advisor.

Before that, it would have been the death of a miliciano.i

Many moons before, it would have been the death of a youth who knew enough, what is necessary, about the system, and sought, as manyii others still do, the best way to challenge it.

A year ago, a trio of journalists from the paid media, sponsored by the government of that Aryan Velasco and his rotten court, spread a lie about Galeano’s murder.

The person who took the photos of the supposed, carefully bandaged blows suffered by the murderers, won a prize a trip to New York to show off their other mercenary photos.

Those who unabashedly swallowed the government’s shit and disseminated it on the front page, are now echoed by those who dress up the news and present Galeano’s murder as the result of a confrontation.

Those who were silent accomplices out of financial convenience or political cunning continue to pretend that they do journalism and not badly disguised propaganda.

Just a few days before this event that has brought us here together, we read in the paid press that the “heroic,” “selfless,” “professional,” and “unpolluted” police from the Federal District in Mexico had a “confrontation”—that’s what they called it—with a group of blind people. Those wicked blind people used their “weapons”—their canes—to attack the poor police officers who were only doing their duty and who were forced to respond with their clubs and shields in order to make those without sight see that the law is the law for those below, and not for those above.

Also recently, in those seasonal speculations that tend to sweep across not only the journalistic profession, but also the social networks, when talking about something is a way to hide the fact that one has nothing important to say or report, a journalist—one of these who claims “professionalism” and “objectivity”—writing about the death of a brother in struggle and collector of rains, Eduardo Galeano, assumed a false link between Galeano the writer and Galeano the teacher, miliciano, and Zapatista.

When referring to the Zapatista compañero Galeano, the paid journalist insisted that he had died in a confrontation, and submitted photos taken by her tourist friend in New York.

I mention that this journalist is a woman not out of misogyny, but for the following reason: as is already common in the press—so common that sometimes it isn’t even reported in the news—murders of women are also disguised as “deaths” and not described as “murders.”

Take any given case, in any home or on any street, in any geography, in any calendar: there is a discussion, a fight, or not even that, but just because he reigns, the man attacks the woman, the woman defends herself and manages to scratch the man, the man beats, stabs, or shoots her to death, and with contempt. The man is treated and his scratches cleaned and bandaged.

About this, the “professional and objective” journalist, as she says, would make the following report: “a woman died in a confrontation with her husband, the man sustained injuries resulting from the fight.” They add photos of the poor injured man, after he is treated in the medical clinic. “The family of the female aggressor would not allow her body to be photographed.” End of the report and of coverage.

That is how today’s news reports are: blind people armed with canes confront police armed with batons, shields, and tear gas. Women armed with their fingernails confront men armed with knives, batons, pistols, and penises. These are the “confrontations” that they report on in the paid media, although some of them disguise themselves as free media, as some have done who registered for the seminar as free media, thinking that we didn’t know who they were and that we wouldn’t let them in if they were from the paid media. But we know who they are and here they are “covering” this event.

The Zapatista compañero teacher Galeano did not die in a confrontation. He was kidnapped, tortured, bloodied, beaten, slashed, murdered and re-murdered. His aggressors had firearms; he did not. His aggressors were many; he was alone.

The “professional and objective” journalist will demand the photos and the autopsy, and won’t receive either. Because if she doesn’t respect herself, and doesn’t respect her work, and that’s why she writes what she writes without anyone questioning her and on top of that gets paid for it, [by contrast] we Zapatistas do respect our dead.

More than 20 years ago, in the battle of Ocosingo which lasted four days, Zapatista combatants were executed by the federal police after being injured in combat. The Zapatistas’ firearms were replaced by wooden sticks. The press was then called to do what they are paid for, under the watch of the government troops. That’s how this lie was woven, repeated incessantly and ad nauseum even today, that the troops of the EZLN went to battle with wooden sticks to face off with the bad government. Sure, there is the small problem that someone took photos when the fallen Zapatistas didn’t have anything by their side. These photos were later compared with those presented by the official press. A lot of money was paid out so that the photos that showed the truth wouldn’t be disseminated.

Today, in the modern times of economic crisis in the paid media, photojournalism—an art—has been transformed into a poorly paid commodity that often only manages to provoke nausea.

I won’t detail each and every one of the injuries suffered by compañero Galeano, nor will I present you with photos of his sullied cadaver. I won’t rehash the narrative cynicism with which his murderers detailed the crime, as someone would recounting a great feat.

Time will pass. The confessions of the executioners will come to light. We will come to know in detail the torture and their celebration at each drop of blood, the drunkenness of cruel death, the subsequent euphoria, the moral and ethical hangover in the days that followed, the guilt that pursues them, the justice catching up to them.

The Zapatista teacher compañero Galeano will be remembered by the Zapatista communities, quietly, without headlines. His life and not his death will be a joy within our struggle for generations. Hundreds of Tojolabal, Tzeltal, Tzotzil, Chol, Zoque, Mame and mestizo children will carry his name. And there will no doubt be little girls named “Galeana.”

The 3 members of the decadent media nobility who beat the drums of war by spreading a lie, who have been silent in cowardice, and the “professional and objective” journalist will all continue to be mediocre; mediocre they will live, mediocre they will die, and history will run its course without anyone even remembering who they were.

And just to end once and for all that silly idea, Zapatista teacher compañero Galeano did not take the name of that tireless collector of the word of below, Eduardo Galeano. This connection was an invention of the press.

Although it sounds absurd, the compañero takes his nom de guerre from the insurgente Hermenegildo Galeana, indeed originally from Tecpan, in what is now the state of Guerrero, and who would become the lieutenant of the independence leader José María Morelos and Pavón. Hermenegildo Galeana was with the insurgent troops when, on May 2, 1812, they broke the siege that the royal army held over Cuautla, defeating General Félix María Calleja’s troops along the way. The insurgent resistance wrote a brilliant page in military history that day.

It is common in Zapatista communities that men and women apply gender pronouns according to their own very particular understanding. For example, the map [el mapa with the masculine article in Spanish] is “la” mapa [with the feminine pronoun]. What the compañero did was “masculinize” the name Galeana, changing it to Galeano. This was years before we came out publicly.

I won’t say much more about the Zapatista teacher, compañero Galeano.

His families and compañero, who honor us with their presence today, will do it far better, as will compañero Subcomandante Insurgente Moises.

His absence still causes me a lot of pain.

I am still unable to make sense of the cruelty with which they treated him, murdering him with weapons and with journalists’ reports.

I am still unable to understand the complicit silence and indifference from those who were assisted and supported by his generosity, and who then turned their backs on his death once they’d made use of his life.

This is why I think that, since it’s his life that we are raising up, it would be better if compañero Galeano were the one to speak to you.

The following fragments that I will read to you come from compañero Galeano’s notes. The notebook, with this and other writings, were handed over to the General Command of the EZLN by the family of that compañero who we are missing here today.

The first notes apparently date back to 2005, and the last ones are from 2012.

He writes:

“Dedicated to all who will read this brilliant history, so that my children and my compañero can never say that it faded away.

I am writing about the actions and steps I have taken in the struggle, but I am also critical, so that they learn from my mistakes and not repeat them. But it does not mean that I am not a compañero.

Well then, I will begin with my earlier life as a youth and a civilian.

When I was about 15 years old, I always participated in the work and the actions of an organization called, “Unión de Ejidos de la Selva.”

I knew that I was exploited because the weight of poverty that fell on my sunburnt shoulders was enough for me to recognize that exploitation still existed, and that one day someone would come to help us rise up and show us the path, someone to guide us.

Well, as I mentioned in the beginning I participated in a tour that (number illegible) we indigenous made in order to exchange ideas about productive work projects. That’s what they called the program our advisors from that so-called Union created and that we were active in.

Well, for me, it helped me learn a lot of things. In the first place, I realized how those damned advisors, Juarez and Jaime Valencia, among others, tried to deceive us. We had gone all the way to Oaxaca, a place where indigenous compañeros like us live, and they also had an organization called X, directed by a priest who was there with them. But they were also in the same situation of oppression that we were.

Well, to make a long story short, we visited many cities throughout the country. It was there where I noticed how many people were begging on the streets, without housing and with nothing to eat. From there an idea took root in me that this should be our objective—to exchange ideas on how to demand a dignified life for everyone who we saw living in such humiliating poverty by fault of the governments.

I also noticed something that disgusted me so that I never again came to depend on those liars and tricksters who pretend to be with those from below. They used to create these movements so that they could get rich off our backs, and we were idiots to believe in their vicious and false ideas.

Why do I say it this way? Well, you will soon see how things were. It turns out that they would promote government programs in order to deceive us, and in turn, have us deceive our own people in our own communities. On that tour, the government gave 7 million pesos of support, which at that time was a ton of money because we were talking about pesos in the thousands, not like now [after the peso conversion in 1993] when we only talk about pesos in the singular. At that time they told us that the government had given 7 billion but that we wouldn’t get it all—just 3 million and that the rest would go to fund the other tours. We never knew what happened to that money.

Of course, they never told us, but that money stayed with the aforementioned advisors, and while we were eating totopo with a little piece of cheese there in Oaxaca, and sleeping in the hallway of the municipal building in Ixtepec, Oaxaca, where do you think they were? Well, they were sleeping in nice hotels and eating in fine restaurants. And that’s how it was until we returned to Chiapas.

When we had arrived in Puerto Arista, they bought themselves cases of beer so that they could get wasted. When it was over, they said that they had to use the 3 million pesos in order to cover expenses. They told us that we would have to eat crackers and drink sodas because there was no more money left. But I knew that it wasn’t true, that the representatives in charge of the accounts tried to make us believe that the money was all gone, but they had already come to an agreement with those idiot advisors. And so I proposed that they count the money again to see if it were in fact true that it had all been spent. But my proposal was not accepted and then they told me that the tour had come to an end in Motozintla. They gave me 40 thousand pesos (of the old currency) so that I could return home because they had budgeted that it was the amount I would spend on transport to Margaritas, but after that, to get to La Realidad, I would have to figure it out myself.

It was damned difficult, 40 thousand of the old pesos that Salinas converted are only equal to 40 pesos today. And that’s how I returned to my village, completely sad and enraged at the same time.

It was in ‘89 when I met a real advisor, a man who used to pretend to be a humble worker, a parrot vendor. He and I were kind of friends, but even though we knew each other, he had never told me who he really was and what he really wanted or what he was really doing. We often encountered each other in the Cerro Quemado and we chatted, and I noticed that he carried a rucksack with his tools wrapped and ready for work. That’s what my friend used to tell me. How many other people like me knew the story of my friend without knowing the real story. It remained to be seen how many lies my friend used to tell back in those days. Lies in order to make truth; lies in order to make Reality. True lies. He was my buddy, and I was so slow that I had no idea what was going on.

Until one day when I bumped into my friend once again, but this time he wasn’t dressed like a humble worker, and he didn’t carry a rucksack, and he didn’t have his parrot cage with him.

So what was he carrying then? Well, there was my friend, my buddy, all in black and brown, with a backpack and shoes, and a weapon over his shoulder. It turned out that my friend was a brave guerrilla and soldier of the people. I was shocked and I went home completely sad and still unable to understand what was going on.

That was my mistake, not understanding quickly enough what that man wanted.

It was then when he knew that I had found him out, and he had me summoned to the safe house along with my parents and siblings. But my dad didn’t want to join and neither did my siblings, but I didn’t give it a second thought. That was how I joined the organization. They called me to train. At that time, almost everyone was already a Zapatista. We went to train. Later they assigned me to the rank of corporal and that’s how it went until all of my family members eventually joined.

The day arrived when I finally learned what my liar true friend’s name was: at that time, he was known as Captain Insurgente Z. This was a man who had to travel all of Chiapas’ indigenous villages, all of its mountains, rivers, and ravines. He walked at night as a guerrilla, during the day as the most humble man in search of work; and all the while sowing, step by step, the seed of freedom until it grew and bore fruit.

How great his suffering had been, but what beautiful fruits he harvested and carried with him. Proudly he received his promotion to Major for his intelligence and brave action and preparation.

But he wasn’t the only one. There was another great, brave, unforgettable revolutionary in the history of our clandestinity. Our beloved Subcomandante Insurgente Pedro, respectfully nicknamed “the Uncle” by all the compañeros of our struggle. Beloved by all because he was a true exemplary who shared his revolutionary wisdom. He was a true teacher of discipline and compañerismo.

I call him an exemplar because he would say that he would be out on the front lines and if it were necessary to die for our people, he would do so.

On December 28 (of 1993), the compañero Sup I. Pedro told me to head over the Margaritas to buy gasoline and some batteries that we needed. He told me to tell compañero Alfredo to take “el Amigo,” (the community car) but not to let him know that the war was about to begin. And so I went. To throw off the driver, we bought shelled maize because it was an emergency trip and that way he would not suspect what was about to take place. Except he already knew, but only as gossip, that the war was about to begin and so he asked about it, but I never said anything because those were my orders, and I fulfilled them although he was my good friend. I didn’t even inform my parents about what was about to happen, because by then they were living in Margaritas. We walked all night and all day.

On the 29th (of December 1993), we returned at about 4pm to Realidad. I had completed my first mission. I gave my report back and he told me, “Prepare yourself because we are going to fight. In half an hour we’ll have forced the police in Margaritas to surrender.” And that always stayed with me. Just like many others of Sup C. I. Pedro’s feats.

And that trip the 30th (of December 1993) to Margaritas continues to stay with me to this day. But also, there were many accidents along the way. Our troops’ advance was incredible. Without the enemy realizing it, we advanced like ghosts in the middle of the dark night, illuminated only by the headlights of the Zapatista cars and buses.

Before reaching Las Margaritas there is a place, before Zaragoza. Near that place everyone dispersed, with their revolutionary assignment: first group, take the municipal presidency; second group, take the Margaritas-Comitan highway checkpoint; third group, take the San Jose Las Palmas-Altamirano highway checkpoint; fourth group, the Independencia-Margaritas highway; fifth group, take the Margaritas radio station.

That was at dawn, on that glorious January 1, when we ceased being phantoms of the night and became the EZLN before the eyes of the world. Everyone saw us with amazement and respect for our courageous act.

That’s how it was when Sup C. I. Pedro fell in combat against the police. He died courageously, killing various police officers. He confronted them alone. His rage against the murderers of the people was so great that he no longer cared about his own life, and with that he fulfilled his promise: die for the people or live for the homeland.

I was shocked when they informed us that our beloved chief had fallen. I felt such a great pain, but he had fulfilled his mission and had also prepared the next in line very well. Because he knew that he would fight and that this sort of thing could happen in war.

That’s when that brave guerrillero, my friend Major Insurgente Z, took up the command. So our missions, although the fall of our great chief was so painful, were directed by Major I. Z. One group went and took over the plantation of Absalon Castellanos Dominguez, taking him prisoner, and brought him to the mountains in order to put him on trial for all of the crimes he had committed while he was governor, for he was the intellectual author of those crimes. In spite of all the charges against him, of being guilty of murdering so many of the children, women, and elderly of Wololchan, his rights as a prisoner of war were respected. He was never once tortured. On the contrary, whatever the troops ate, he was given to eat as well. That’s how our comrade once again demonstrated the education and military experience he had gotten during the clandestine period. The lives of those who fall prisoner in a war must be respected. And it is a reminder for all who read our history that respect is earned by respecting those below, but also those above if they demonstrate respect to those below. Dying to live. Galeano.”

(continues)

“In Las Margaritas I had the task of creating a checkpoint on the Margarita San José Las Palmas highway. From there, we were transferred to the Margaritas-Comitan highway. That’s where we were on January 1, all night long until we received the order to take the Conasupo warehouse that was over in Espiritu Santo. We went with other compañeros insurgentes to take things from there so that the troops could have something to eat. Then the order was given for us to retreat to the mountains and so we came and positioned ourselves at Guadalupe Tepeyac. After that we ambushed La Realidad at kilometer 90, Cerro Quemado. And then they sent me to recover a 3-ton vehicle that belonged to this bastard named J from Guadalupe Los Altos.

I didn’t know how to drive well. I only knew how to drive a vehicle in theory, and so that’s when I got my practice and the vehicle started to move. I reached La Realidad using only the first gear the entire time. They were already waiting for me, the compañera Captain L and many other insurgentes, and they told me, “Let’s go Galeano,” and I said, “I haven’t even driven and much less given anyone a ride.

Dying to live. Galeano.” (written between 2005 and 2009)

(continues)

“It doesn’t matter, all’s fair in war,” the compañera replied. And so we went up ahead, past Cerro Quemado, I was gaining confidence and I started going faster, but at a curve I turned the steering wheel too far and I ran off the road about 15 meters into the tall grass beside the highway. But well, I managed to get us out of there and I drove on in order to fulfill my mission.

From that day on, I started driving every day until one day a helicopter spotted us and it began to shower me with bullets. It shot at me for about 10 to 20 minutes, but I had taken cover really well under a rock. Only dust and the smell of rock and gunpowder reached me. And it wasn’t until the gunfire ceased and the helicopter retreated that I left my hiding place and continued on with my mission. The mission was to pick up the milicianos who were near Momón. I headed over there and returned with my friend and military chief, the compañero Major Insurgente Z. We were always together during those days of war, even during the ceasefire.

With the work of the first Aguascalientes in Guadalupe Tepeyac, I participated in receiving the people who came to the National Democratic Convention. They trained me as a bodyguard; I was a bodyguard for our leadership.

Later, the day of Zedillo’s betrayal, on February 9 we went to block the highway at Cerro Quemado. The army was already at Guadalupe Tepeyac. But we still advanced in darkness and worked at building ditches and felling trees in order to prevent the federal troops from making it to La Realidad.

Next, we retreated to the mountains for several days until, once again, the people of Mexico and the world mobilized and prevented the persecution of our EZLN leadership and troops. After many days of encampment in the mountains, we returned to our villages.

I participated in all of the encounters that our organization organized. I escorted our military chiefs. I participated in the march of the 1,111 Zapatistas to Mexico City. In all of the marches, I always traveled proudly as the driver of “El Conejo,” “El Tata,” and “El Chocolate.” I always took our compañeros to the marches in order to make our demands. When all of the sergeants got cold feet, I remained and they promoted me to sergeant. I was a regional organizer for the youth during in times of clandestinity and in times of war. We have made war against the enemy a thousand and one ways, although the bad government has done the same thing too.

We should value the great paths we have traveled no matter the sacrifices and deprivations. They have all made us much stronger and they keep me along the path of struggle, until we find the freedom that our people need. There is still much more to travel because, true, the path is long and difficult. Maybe it is close, maybe it is far, but we will win.

After that, the Good Government Councils were formed and they chose me as the driver for the first truck obtained by the Good Government Council. It was called “the Devil.” Later I was kidnapped together with another compañero, and the CIOAC-Histórica tied us up and took us in that same truck. They had me tied up for several hours before transferring me over to a jail in Saltillo. Then they transferred me to Justo Sierra and left me there without food, tied up, without communication. They wanted me to demand that one of their delinquents be released, but I refused to be exchanged because I was innocent and he was one of those thieves who abound in social organizations.

I was held captive for 9 days until they recognized that they were getting themselves into problems with human rights and with the EZLN. And finally they released the truck after holding it for 3 months. And after that, the truck got a name change: “The Historic Kidnapped.” That was when the work of the Good Government Councils and of autonomy began. Dying to live. Galeano. January 24, 2012).”

This is the last date that appears in his notebook. Next to that brief autobiography, appear a pair of poems, probably his own, and some songs about love and that sort of thing.

For my part, all that’s left for me to do is add that the Zapatista teacher, compañero Galeano was just like all the other Zapatista compañeros and compañeras, somebody worth dying for, so that they may be reborn.

Upon finishing these lines, maybe there is a response to a latent question—a question planted in the middle of the kind of history that is not written with words:

Who or what made it possible that a space of struggle could witness the convergence of a Zapatista philosopher and an indigenous Zapatista?

How was it that, without ceasing to be a teacher, the philosopher became a Zapatista, and the indigenous, without ceasing to be a Zapatista, became a teacher?

Something happens in the world that makes this and other absurdities possible.

Why, in order to live, one bequeaths to their loved ones a hidden piece of the puzzle of their story?

Why, in order to not leave, the other leaves us letters in which their gaze is turned on themselves and their history with us Zapatistas?

This is what we try to answer every day, every hour, in ever corner.

Now, as I am about to place the final period on these words, the answer occurs to me, or at least a part of it: it is seated at that table, it is within those who are in front of and behind me, it is in the worlds that lean over to peer at the struggle of those, with secret pride, call themselves Zapatistas, professionals of hope, transgressors of the law of gravity, persons who, without a fuss and in each step say: IN ORDER TO LIVE, WE DIE.

From the mountains of the Mexican Southeast.

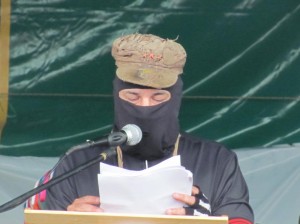

Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano.

Mexico, May 2, 2015.

The compañera Selena, Zapatista-escucha [a cargo of listener], now has the floor …

i� Member of the EZLN’s civilian militia or reserves

ii� The text uses “muchos, muchas, muchoas” for “many” to give a range of possible gendered pronouns including male, female, transgender and others.

(Continuar leyendo…)