Portugal // Against the disinformation campaign about the lithium mine in Barroso

The british mining company Savannah and the disinformation campaign about Europe’s biggest project of lithium mine in Covas do Barroso, in the north of Portugal.

A few months ago we had the honor of appearing on prime time in the portuguese television and seeing one of our articles dissected by the fact-checking of Polígrafo/SIC. It’s a pity that these respectable organizations don’t fact-check the mass media, which so often misrepresent reality and behave as organs of disinformation.

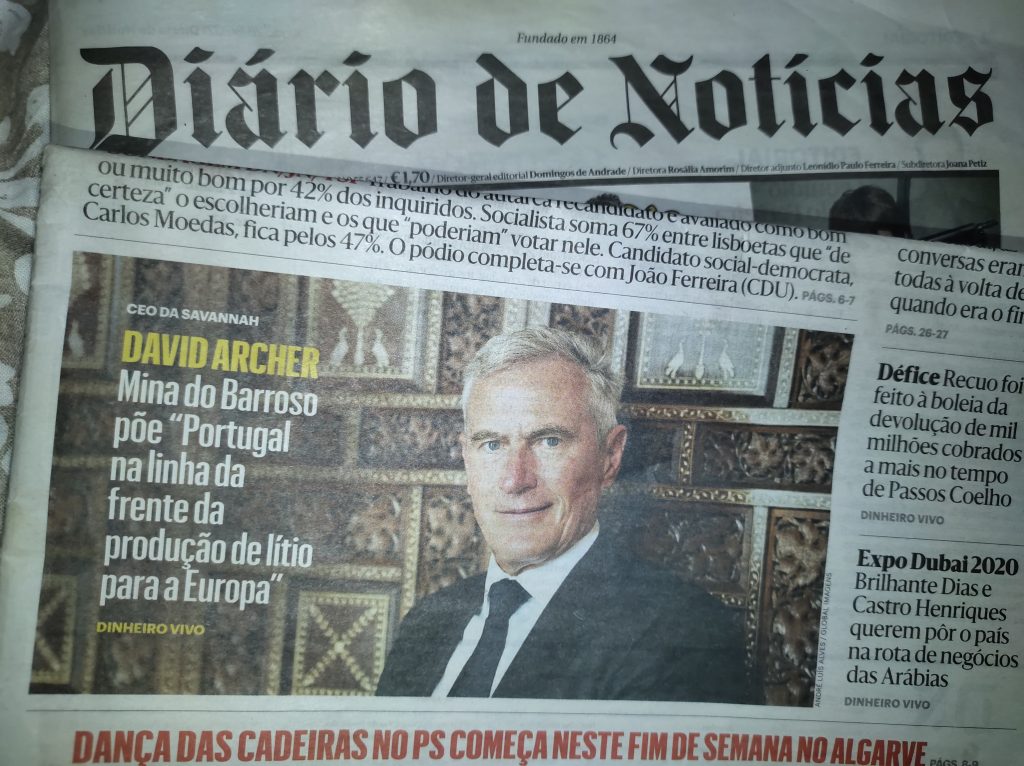

On saturday september 28th, it was published in the supplement Dinheiro Vivo (Living Money) of national newspaper Diário de Notícias – covering both front pages – an interview by the journalist Joana Petiz with David Archer, CEO of the british Savannah Resources. This mining company wants to open an open-air lithium mine of 593 hectars in Covas do Barroso, in the north of Portugal. This interview, disguised as journalism, is part of a campaign of disinformation and free publicity driven by Savannah and several media.

The cherry on top of the cake is the editorial, signed by the same Petiz, which goes along with the interview. An editorial in an insulting and ridiculing tone towards the Barroso population that for several years has been organizing and mobilizing in defense of their territory.

Facing the silence of the recognized fact-checking projects, we have decided to subject these two pieces to a rigorous fact-check ourselves, for which we will proceed without further ado.

Barroso – A «moribund region»?

In her editorial, Petiz classifies Barroso as «a region increasingly deprived of people and of means of subsistence or diversification of sources of income.» What she classifies as a «moribund region» is actually classified by the FAO as Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) since 2018 «based on the traditional way of working the land, treating livestock, and on the mutual aid of its inhabitants.» It is the only region in Portugal with this classification and one of the 7 in Europe. Much of the region is also part of the Gerês-Xurés Transboundary Biosphere Reserve, created in 2009.

In this region, the “means of subsistence” and the “sources of income” come greatly from agricultural activity and cattle raising, namely from the Barrosã breed. This is a cattle breed that has already been in danger of extinction, precisely during the periods of greatest mining activity in the region (mostly tungsten extracted in galleries until the 80s), and its meat is, according to many, the best in Portugal.

Most part of the villages still have communal lands, the “baldios”, which continue to be collectively managed. In many parts of Barroso, other ancestral practices of collective management of water and other resources are also preserved. In the villages that we come across in the mountains, one can also find a dynamic cultural and associative life.

If it is true that it is a region with an aging population and that it has been losing population in the last decades, like almost the entire portuguese countryside, this is anything but a dying region «deprived of people and means of subsistence».

From the 800 jobs to the smart mines

In the interview, David Archer claims that the mine will create «about 200 direct and 600 indirect jobs», numbers already known from the Environmental Impact Study (EIA) presented by the company and certainly based on the serious predictions of a renowned expert. Archer goes even further, suggesting that «in those 200 direct we are talking about families, so the impact of people who benefit may be three times greater».

Whoever has been to Barroso, and got to know the people and their way of life, easily understands what a huge number of open-pit mines represent for a region that lives from agriculture and animal husbandry.

The explosions, the dust, the deviation of water courses for its use in mining and the contamination of the remaining rivers are incompatible with this lifestyle. Even more so when we talk about mines that will be just 40 meters away from the nearest houses, in the case of the Borralha mine, or 200 meters away, in the case of the mine planned for Covas do Barroso.

In these studies and forecasts, they count jobs from who knows where, but they don’t count the people whose subsistence is threatened by these projects. If all the mining projects for the Barroso region were to go ahead, how many hundreds of farmers, shepherds, cattle ranchers, and beekeepers, and their families of course, would have to abandon the way of life they have always known?

Back to the 200 jobs… If we ask ourselves what jobs are those, and who will benefit from them, we will find the answer in that same interview. David Archer states that «they are specialized jobs like nurses, geologists, environmental scientists, accountants, IT technicians, that means, careers of value and with salaries above the average of the region». In other words, certainly not for those hundreds of families that live off agriculture and livestock, but for people coming from outside.

But they will certainly need a lot of non-specialized workforce for projects this big, won’t they? Archer clarifies: «We are (…) in collaborations with lots of Portuguese companies (…) to develop a smart mine, which is remotely controlled with a series of environmental monitoring sensors, which provide real-time information by app, etc.»

That is, automated processes, where much of the work is done or assisted by machines. These job promises are used to try to buy off local populations, but they are not even for them. To see what the promises turn into, just look at the Lousas mine in the neighbouring parish of Couto de Dornelas, where Felmica has been extracting quartz and feldspar since 2008. The jobs do not reach… a dozen.

The mine, the development of the region, and the work with the community

In the interview, David Archer affirms: «this project (…) will bring demand for housing, [has the potential to] catalyze relocation of public services – schools, health services, post offices, etc. The mine will be part of the solution to revitalize this region and reverse desertification and it will bring market for agricultural products, and encourage those productions and other activities as well.»

But, after all, how do you revitalize and reverse the desertification of a region by digging holes in it? Who will want to live next to huge craters, next to daily explosions of 720 kilos – in the case of Borralha Mine -, to see from the window of their house heaps almost 200 meters high – as they plan to do in Covas do Barroso?

After all, how do you create a market for agricultural products and encourage these productions and activities in an area full of mines? Who will want to eat meat from cows that live in the middle of dust, contaminated soils and water? Who will even be able to be a shepherd or raise cattle under these conditions? Or a beekeeper? Or a farmer?

Petiz’s questions drive the interview comfortably for the CEO, avoiding difficult and critical questions. She even shares the information herself about Savannah’s fantastic programs with the community: «Savannah Lithium has also set up 600 thousand euros/year compensation funds to work together with the community and in good neighbor programs. How will that materialize?»

To which Archer replies: «It could be professional schools, actions to promote local businesses, training, it could be the purchase of ambulances». Because, in their view, the Barrosões are a bunch of peasants who will let themselves be bought for anything. Except that they don’t.

Sustainability, responsibility and climate change

Asked about the APA’s final decision on the Savannah Mine Environmental Impact Study, Archer says that «we have delivered a responsible proposal for sustainable development» and that «we don’t expect a disapproval. We believe that we are doing responsible development to move forward in a way that benefits all Portuguese people because this (…) is an asset that benefits the whole country.» He states that there are a series of mechanisms that ensure «the progressive mitigation of the effects during the time of exploration and at the end of the mine’s life» and even suggests that, when the mine is deactivated, «the hole will be transformed into a lake for recreation or eventually into facilities that allow exploration of renewable energy.»

In both articles, Savannah is always presented as a responsible and sustainable company. Reading this interview, we find a wonderful project that will benefit «the whole country» and «all the Portuguese people». Everyone, except the Barrosões.

There have been 170 participations in the EIA public consultation period, by environmental associations, local associations and movements and the Boticas City Council, with opinions from many other specialists on how the project contaminates the land and water and puts protected species and the region’s populations at risk. But for Petiz this seems to be just a minor detail, so much so that she only mentions it, briefly, at the end of the 4-page interview.

Associated with this comes the building of the idea of a Savannah that wants to act for the common good, defend our planet from climate change, and not seeking profit at any cost. We are told by the Australian businessman “with particular experience in gold mining”:

«The development of the lithium industry has brought us a new hope to truly act for change against climate change. And electric mobility will allow an incredible improvement of life in Europe, in our cities, in air quality, with positive impact in all areas, reducing CO2 emissions. And lithium is the raw material that makes that change possible. You can’t make these batteries without lithium.»

We could dismantle this speech by explaining in detail that lithium cars are not sustainable because the batteries have a short life span (somewhere between 4 and 10 years), which can be even shorter if the battery is exposed to hot climates; that there are several difficulties and obstacles to their recycling; that the price of these cars is very high, being accessible only to a reduced elite; that the “energy transition” and “electric mobility” are still based on the logic of the individual car, being nothing more than a technological transformation that benefits the same people as always and not a paradigm shift, as would be the creation and strengthening of collective transport networks and the recovery of technologies such as streetcars, which have existed for over a century and do not need batteries to work.

But more important than this is to check this statement by David Archer that «lithium is the raw material that makes this change possible» and that «you can’t make these batteries without lithium». Is that so?

China recently made headlines in several national and international newspapers for looking for a «viable alternative» to lithium due to its «shortage and its increasing price and demand». The development of sodium batteries is already in progress.

According to the Chinese company CATL, «Sodium-ion batteries contemplate recharging up to 80% of their capacity in just 15 minutes and promise high energy density and good thermal stability in a variety of scenarios. This last aspect is especially important and an advantage over lithium, which loses performance when it is too hot or too cold».

The first batch of sodium batteries produced on a large scale is planned for as early as 2023, before Archer’s target date for the Savannah Mine to be in full operation, 2024.

But there are more alternatives. Episode 30 of RTP2’s Biosfera program focuses on eco-friendly batteries, alternatives to lithium. They talk to researchers from various universities who explain several types of batteries that they have already developed – flux batteries, vanadium batteries, batteries that combine salt and caustic soda, among others.

These are batteries that are non-flammable and non-toxic, or more durable and use materials that are easy to reuse and recycle, or all at the same time. More efficient and less harmful to the environment than any lithium battery available today.

Maria Helena Braga, researcher and professor at the Faculty of Engineering of the University of Porto, developed a battery that uses salt and caustic soda to store energy and, at the same time, to self-charge. This battery combines negative capacitance and negative resistance in the same cell, which allows it to self-charge without losing energy. The researcher warns, still, that this «is not a perpetual energy supply machine». However, Maria Helena «still has at home the first battery she produced, and has been using it as a continuous supply of electricity since the summer of 2015. Which means, although it is not a source with an infinite time, its self-charging has already lasted for 5 years», explains the journalist.

But, if we have the necessary technologies to produce cell phones, computers and cars with more sustainable and durable batteries, why aren’t they introduced in the market? Maria Helena Braga explains:

«What I have learned from these last years (…) is that this does not depend of science, it depends much more of industry. The industry has to come, has to pay, has to have the equipment, has to make a factory… (…) What happens is that the industries have invested a lot in lithium ion. (…) The other question I raise: battery companies have to sell batteries, if they last a long time without having to be replaced, the industry loses. We win as consumers, nature wins, but the industry…»

EU – Environmental Regulations Paradise

Another argument with which David Archer defends his mine is that «It is better to produce according to European environmental laws, which are much tougher and more serious in Europe, and in a political context of leadership for sustainability (…) than to go, for example, to the Democratic Republic of Congo.»

Joana Petiz, who did the interview with David Archer, reiterates the idea in her editorial: «a mining operation limited by the tight european regulations will always have every advantage over a project developed in a region of the globe where money speaks louder than any precautions – environmental, economic development and even human rights.”

An arrogant, paternalistic, colonialist tone of despise toward the other regions of the planet. As if in Europe money did not speak louder than any environmental precaution and human rights. As if environmental disasters didn’t happen also in Europe as a result of corporate and government negligence. As if in 2010 there wasn’t a toxic mud disaster in Hungary. As if in Almaraz, on the banks of Tagus river, there wasn’t a nuclear facility which closure is repeatedly postponed despite frequent accidents. As if in Portugal, until three or four years ago, they weren’t talking about fracking and petroleum extraction off the coast of Alentejo and Algarve. As if a large part of Andalusia, and now also Alentejo, were not given over to intensive agricultural production that drains the already scarce water and employs migrant people in conditions that do not respect the most basic human rights. As if the municipalities did not commit environmental offenses, violating the environmental laws and regulations for certain interventions, with the connivance of the Portuguese Environmental Agency (APA), which is supposed to ensure compliance with these laws – as happened with the destruction and leveling of the Mondego riverside strip between Rebolim and Portela, by Coimbra’s city council, destroying the riparian galleries which are protected ecosystems. As if the APA would not approve projects that even the courts would reject, as is the case of Montijo airport, whose Environmental Impact Statement emitted by the APA was rejected by a judge at the Almada Administrative Court for «evidently and manifestly neglecting the environmental impacts, both in the construction phase and in the operation phase, on legally protected sensitive areas of national, communitarian, and international importance». As if so close here, in Touro, Galicia, in a copper mine that was deactivated in the 80’s, acid drains were not continuously contaminating the waters of the area.

The anti-mining movements

The most offensive of all are the insults against those who are fighting against the destruction of about 10% of our territory by open-pit lithium mining, planned by the government in connivance with the European Commission and the mining companies, and just as much by the extraction of other minerals.

Petiz calls us “wannabe environmentalists” in “hollow and selfish wars” – «Marches against the wind shovels that kill little birds, protests against dams that spoil the ecosystem, popular uprisings that raze solar panels that heat the air.» «The people protest for clean energies but are fierce opponents of all the means that enable them.»

The people are not against clean energy. The people are against that, on the pretext of a supposedly “clean” energy that is not clean, the territories and the ways of life of people and future generations are destroyed. Without consulting or even informing the local population. All so that, in this case, a small urban elite can move from one place to another without a guilty conscience, without wondering what happens to the regions where the raw material comes from or what happens to the lithium batteries at the end of their useful lifespan.

In the interview, Petiz asks at one point: «Since lithium is essential to the energy transition – which these organizations defend – do you see this opposition to lithium exploitation here as a “not in my backyard” issue?» Archer replies: «It doesn’t seem right to me that consumers want green electricity but don’t want to be involved in the raw materials needed to power it.»

David Archer overlooks the recent movements and manifestations stating that «a lot of what these movements are and a lot of the protesters come from France and other countries, they are part of an anti-development group that protests against all kinds of projects.»

If we look at the Camp in Defense of Barroso, in Covas, we see that it had the participation of people coming from all over Barroso and from all over the country – from cities and other villages and towns with anti-mining movements -, from various parts of the Iberian Peninsula, from Switzerland, from Mexico and, yes, also from France. They were present because many also face megaprojects in their regions and are interested in knowing what is happening in other places and supporting the other struggles. Because they know that these problems are not just problems of their backyard, but common problems for all humanity, in all parts of the world.

The system panics facing the growing mobilizations

In Barroso there is a growing mobilization and resistance against the several mining projects in the region, especially strong this month of August. Environmentalists, journalists, and many other people have seen with their own eyes the village and the region, have gotten to know its people and their struggle, as well as other neighbouring struggles also present, and are now carrying them back to their villages and cities, to their own movements.

Before, during and after the camp, while the portuguese conventional media remained more or less silent about this initiative, reportages were published in Spain, Mexico [1 and 2], Turkey, Germany [1, 2, 3 and 4], France, Basque Country, Mozambique and Indonesia. In-depth reports had already been published in the past by French television ARTE and even by Euronews.

These two articles and the covers of DN and Dinheiro Vivo are a necessary move for the system to cope with the growing mobilization in Barroso. A move deprived of journalistic ethics to try to control the lithium and mining narrative, exalting how spectacular and green it will be, all in the name of the “energetic transition”, of the “green mobility” and of a more sustainable world, never in the name of the interest and profit of a handful of private individuals.

The truth is that they are frightened by the unity and determination of the Barrosão people in the defense of their territory.

They treat Barroso as a dying region that needs to be saved by the enlightened lords of developed cities. Behind the pretty speeches hides the will to destroy a paradise on earth in the name of the greed of a handful of investors and CEOs. And in some other underdeveloped or dying place that nobody knows about, a graveyard of “green” batteries full of toxic and contaminating substances, which no one knows how to recycle, is also born.

Much of the arguments we use used here can be easily found in a quick search. Petiz says that «the attitude of those who behave this way» [who contest lithium] «is neither serious nor responsible». What is not serious is her work as a so-called journalist. Petiz treats the people of Barroso as fools, but she is the one playing the fool.