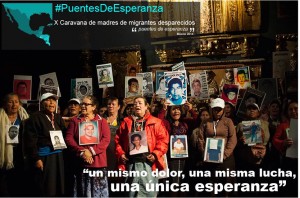

Migrante viajando en el tren La Bestia. Foto: Alejandro Gálvez

Por Alejandro Gálvez

ATITALAQUIA, Hidalgo, México.- María, una joven hondureña que no rebasa los 25 años, lleva casi una semana viajando en el techo del vagón de un tren; ha recorrido miles de kilómetros desde la frontera entre Guatemala y Chiapas, fijándose la meta llegar a los límites entre México y Estados Unidos, cruzar y en el mejor de los casos con un golpe de suerte lograr el anhelado americandream.

La tragedia viene incluida en el escueto equipaje de María; tan dramático como desgastante ha sido su recorrido; un día, mientras dormía en el ardiente techo del tren, vapuleada por la fatiga y el hambre, no reparó en que su hijo de apenas unos meses de nacido se le escapó de los brazos. No sintió nada, no vio nada. Kilómetros más adelante, cuando el tren hizo una de sus tantas paradas obligadas, el sobresalto se apoderó de María, al abrir los ojos y advertir que su pequeño hijo se había caído desde lo alto del tren, en algún lugar, quizá muy cerca, quizá muy lejos, nunca sabrá.

Con la misma suerte corrió un menor hondureño de apenas 5 años de edad; en su aventura para llegar a los Estados Unidos, el infortunio lo tocó, y cayó de lo alto de un vagón, mientras jugaba con un grupo de centroamericanos, con quienes bromeaba y platicaba para hacer más llevadero el martirio disfrazado de viaje en tren.

Albergue para migrantes en Casa del Samaritano, en Fracc. Bojay, Atitalaquia, Hidalgo. Foto: Alejandro Gálvez

Una historia más:

Durante su viaje, un grupo de migrantes son interceptados por unos delincuentes que salieron de entre las arroceras; con machete y escopeta en mano, con violento grito advierten:

“¡Esto es un asalto cabrones, no se muevan o se los carga la chingada!”.

Paralizados por el miedo, los centroamericanos obedecen a sus agresores; separan a los hombres y mujeres; a los varones los desnudaron y los pusieron en posición de lagartijas, les quitaron los zapatos y el dinero. De entre las muchachas escogieron a una, la metieron al monte y la violaron. El esposo de otra pidió no le hicieran nada a su mujer, pero uno de los asaltantes dejó en claro que en esos momentos “los ruegos no valían”, y ordenó le cortarán la cabeza a la joven.

Casos como estos sorprenden, incluso impactan y dejan con la boca abierta a la opinión pública y a los propios periodistas, testigos fieles de una decena de testimonios que desnudan las atrocidades más inverosímiles a las que son sometidos los migrantes centroamericanos a su paso por nuestro país a bordo de la llamada Bestia.

Extorsiones, vejaciones, asaltos, violaciones, golpizas, asesinatos…es con seguridad a lo que se enfrentan los migrantes que provienen principalmente de Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala y Perú.

Esto lo sabe Oscar Rolando, un joven hondureño de apenas 17 años, quien dice haber escuchado historias horribles de lo que le pasa a los migrantes, sean hombres, mujeres y niños, “a todos por igual”, sobre todo en los estados controlados por las bandas del crimen organizado.

Pero parece no inmutarse, al contrario, asegura que vale la pena arriesgar la vida para llegar a los Estados Unidos “allá hay dólares, en mi país no hay nada, ni siquiera trabajo”.

“Lo hemos visto todo, hemos pasado por todo, sabemos que con el simple hecho de estar montados en este tren, nos estamos jugando la vida, pero así es esto”, suelta en tono rudo un migrante hondureño que se identifica como Pepe, un tipo delgado, tez morena, quien cubre su negro pelo largo con una gorra sucia, decolorada ya, evidencia fiel de los intensos rayos del sol.

“Mira, aquí traemos pa´ defendernos de los que nos asaltan”, dice amenazante, al tiempo que empuña con fiereza un machete tan largo como oxidado; esto provoca el malestar de sus compañeros, quienes lo regañan y a punta de gritos le exigen guarde el arma.

Pepe no es el único que ha tomado sus propias medidas de seguridad para el camino, -pues a decir de Antonino Ramos Sierra, uno de los encargados de la casa del Migrante el Samaritano, ubicada en la comunidad de Bojay en el municipio de Atitatalquia, “algunos migrantes viajan con machete, no es que quieran matar a alguien, solo lo hacen para defenderse”.

El 23 de marzo del 2011 comenzó a funcionar la casa del Samaritano en el fraccionamiento Bojay, municipio de Atitalaquia en el estado de Hidalgo; se ubica a la orilla de las vías del tren, donde diariamente llegan decenas, a veces cientos de migrantes centroamericanos, hambrientos, sedientos, con los pies llenos de ámpulas, enfermos, algunos con heridas graves, pues llegan a caerse del tren.

En la casa del Samaritano, se les brinda atención a los centroamericanos; les dan de comer, se les obsequia ropa, zapatos, agua, incluso tiene varias camas para quienes necesiten pasar la noche. La casa del migrante es un espacio que ha sido dividido en tres, tiene dormitorios con baños, cocina, y una pequeña bodega donde se guarda la ropa recolectada y algunas medicinas básicas.

En este lugar los servicios básicos son irregulares, el agua escasea, la basura pasa cada ocho días, los baños no tienen regaderas, tampoco tienen calefacción.

Desde su apertura en marzo del año pasado, la casa del migrante en Atitatalaquia ha atendido a más de 60 mil migrantes, de los cuales dos mil han sido adolescentes, explican las hermanas encargadas del sitio asistencial.

“Hemos detectado que algunos de los migrantes son proclives a ser víctimas de trata. En algunos casos hemos visto a adolescentes que estaban a merced de los coyotes y decidimos ayudarles”, añaden las hermanas.

Ramos Sierra, refiere que el viacrusis que pasan los migrantes en su recorrido buscando el utópico objetivo de llegar a los Estados Unidos es tortuoso, injusto, y lleno de hechos trágicos, “que ni siquiera en una película de terror se han visto”.

Por ejemplo, indica que existen grupos de delincuentes que operan en la zona de Atitalaquia; esperan la llegada del tren y mientras hace su parada obligada, roban el material reciclado (fierro); después los policías, e incluso los propios ferrocarrileros culpan e incriminan a los migrantes en los robos.

“Hace unas semanas por poco y me llevan al bote a mí también, porque unos muchachos se vinieron a robar el fierro reciclado de los vagones, cuando llegaron los policías se querían llevar detenidos a los migrantes, yo intervine, porque me di cuenta de todo, y sólo porque traía mi credencial de la casa del Samaritano me salvé, pero ya me querían detener también”, relata Ramos Sierra.

Migrantes en espera del tren en su paso pro Hidalgo. Foto: Alejandro Gálvez

Con todo y la labor social que la casa del Samaritano hace a favor de los migrantes, los encargados se enfrentan al desprecio y el rechazo producto de la xenofobia de los vecinos del fraccionamiento Bojay, quienes están solicitando el cierre definitivo del lugar, pues a su juicio, los migrantes centroamericanos “son personas repugnantes, sucias y fachosas que dan mal aspecto a la colonia”.

Al menos así lo explica Ramos Sierra, quien dice “pueden estar sucios, y fachosos, pero no se meten con nadie, son personas tranquilas, que lo único que buscan es comida y ropa”.

La hermana Luisa Silverio Cruz, quien atiende también en la casa del migrante, coincide con Ramos, y asegura que para los vecinos de Bojay “ser centroamericano es sinónimo de mugroso, delincuente, violador y asaltante”.

Antes de la llegada de los reporteros, en el lugar reposaron y comieron una mujer con siete meses de embarazo y sus dos hijos pequeños, al parecer venían de Honduras, “solo se bañaron, descansaron un poco y se fueron caminando, porque el tren tuvo una falla y no salió, caminarán como unos 5 kilómetros hasta que encuentren al próximo tren”.

-¿Una mujer embarazada, caminando 7 kilómetros con semejante calor?.

“Eso no es nada joven, si usted escuchara todas las historias que yo he escuchado, no las creería, sería bueno que un día se dé otra vuelta, y pregunte usted mismo, se asombrará”, concluye Ramos Sierra.