Sorry, this entry is only available in Español. For the sake of viewer convenience, the content is shown below in the alternative language. You may click the link to switch the active language.

Las organizaciones firmantes lamentamos la inacción de las autoridades de Chiapas y del gobierno federal para atender adecuadamente la urgencia humanitaria de más de 5000 indígenas tsotsiles en desplazamiento forzado en los municipios de Chalchihuitán y Chenalhó, Chiapas.

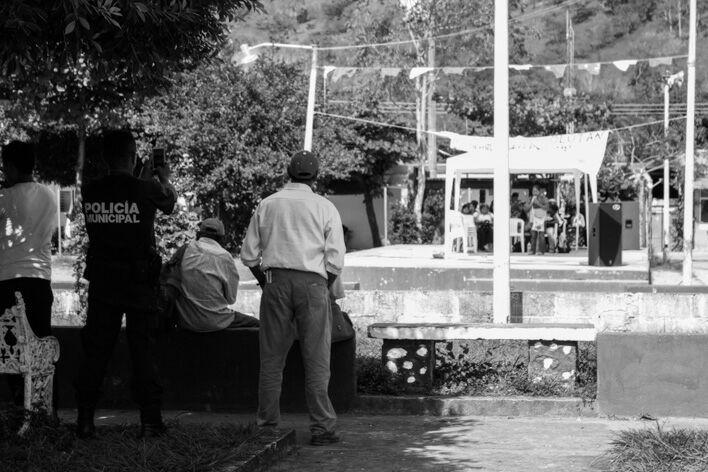

El pasado 9 y 10 de diciembre organizaciones de la sociedad civil de Chiapas, acompañadas por el Movimiento Sueco por la Reconciliación (SweFOR) realizamos una misión de observación y documentación de derechos humanos en el municipio de Chalchihuitán, entrevistándonos con las familias desplazadas, autoridades comunitarias, así como con autoridades municipales.

La misión de observación pudo verificar el clima de tensión y miedo que viven las personas desplazadas así como las y los pobladores de la cabecera municipal de Chalchihuitán.

Según los testimonios, nos indican que después del asesinato del Sr. Samuel Pérez Luna en Kanalumtik, Chalchihuitán, el día 18 de octubre del presente año, se profundizó la violencia y los disparos de armas de fuego sobre todo por las noches, por lo que desde esa fecha varias familias dormían en la montaña y por el día regresaban a sus domicilios a dar de comer a sus animales. Hasta el día 5 de noviembre cuando se desplazaron forzadamente debido a los disparos ocasionados por los grupos armados.

A pesar de lo difundido por el gobierno de Manuel Velasco Coello de estar resolviendo esta problemática, evidenciamos una crisis humanitaria: personas enfermas debido a la situación de desplazamiento, la falta de medicamentos y de una atención médica urgente y adecuada; carencia de alimentos apropiados a la cultura y a una alimentación sana, así como condiciones de salubridad en general que no solamente vulneran el derecho a una vida digna, sino que incluso ponen en riesgo la vida de las personas desplazadas, no sólo por el temor de ser asesinadas por los grupos armados, sino también por la ineficacia de las autoridades de Chiapas para atender la situación de acuerdo a los lineamientos de los Principios Rectores del Desplazamiento Forzado de la Organización de Las Naciones Unidas y la Ley para la Prevención y Atención del Desplazamiento Interno en el estado de Chiapas.

Durante la misión pudimos constatar el corte y destrucción de la carretera en el tramo Las Limas – Chalchihuitán, único tramo carretero pavimentado para llegar a la cabecera municipal. Recordamos que la destrucción de dicha carretera fue realizada con maquinaria por parte de pobladores armados de Chenalhó como una forma de sitiar y controlar a la población de Chalchihuitán. Dicho corte ha impedido el ingreso de vehículos que abastezcan de alimentos, medicamentos, suministros e insumos a la población y quienes cruzan caminando lo hacen con miedo a ser asesinadas.

El abandono institucional y la pobreza estructural es histórica en el municipio de Chalchihuitán, siendo uno de los municipios más pobres y marginados de México, la situación de violencia que ahora se vive en ese municipio viene a profundizar mucho más este estado de vulnerabilidad social, donde las mujeres, niñas y niños se encuentran en mayor riesgo.

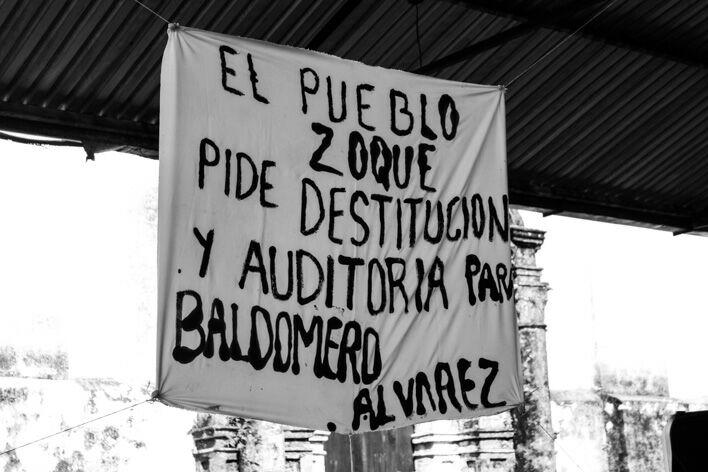

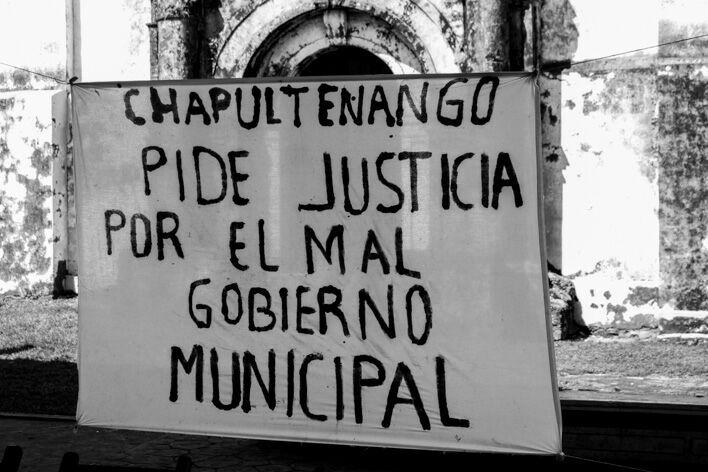

La misión de observación pudo constatar a través de diversos testimonios y entrevistas realizadas, la existencia de grupos armados, que operan de manera abierta en estos municipios, sobre todo en Chenalhó y cuya actividad es permitida por las autoridades de Chiapas y del gobierno federal. La responsabilidad de los partidos políticos es evidente en este conflicto, ellos a través de sus estructuras municipales y estatales han abonado a la impunidad.

En Chalchihuitán hay un clima de terror debido a la acción impune de los grupos armados, la violencia ha afectado a toda la población del municipio por la escasez y altos precios de los alimentos. Vemos con preocupación que por miedo a ser asesinados los pobladores no pueden ir a sus cultivos, perdieron lo de esta cosecha y no han podido sembrar para la próxima temporada como consecuencia no tendrán maíz, frijol y demás productos del campo para poder vivir, lo que pronostica una crisis alimentaria.

Observamos que niñas, niños y adolescentes están viviendo en condiciones inhumanas. Visten con la ropa con la que fueron obligados a salir de sus casas, que no es la adecuada para protegerse de las bajas temperaturas que se presentan en esta época del año. Además, hay numerosos casos de infecciones gastrointestinales y en vías respiratorias, y la alimentación es insuficiente e inadecuada. El suministro de alimentos procesados por parte del gobierno estatal, a los que no están acostumbrados, les provocan diarreas y agravan su condición de salud. Niñas y niños tienen miedo de que los maten, sueñan que les disparan, duermen intranquilos; están tristes, su entorno ha cambiado de manera abrupta. Tienen dolor de estómago y cabeza por la ansiedad y estrés que provoca el desplazamiento. De acuerdo con la información proporcionada han fallecido infantes en desplazamiento.

Las condiciones de por sí graves en las que se encuentran se exacerban por las condiciones preexistentes de pobreza en la que vive el 97% del municipio1 y por la impunidad, negligencia y omisiones del Estado para atender la situación de conflicto. En Chalchihuitán la tasa de mortalidad infantil en niñas y niños menores es de 166 por cada mil, trece veces más que a nivel estatal.2

Constatamos la situación que viven la mujeres y niñas en situación de desplazamiento: la nula atención a una salud adecuada para ellas de acuerdo a sus necesidades, la vulnerabilidad y riesgo en la que se encuentran por la estructural violencia de género acentuada en condiciones de desplazamiento.

Las mujeres entrevistadas informaron sentirse con temor, preocupadas y enojadas porque han sido excluidas totalmente de las decisiones sobre la resolución de un conflicto que les afecta directamente. Recordamos que Chalchihuitán y Chenalhó son municipios que han sido señalados como parte de la Alerta de Violencia de Género (AVG) y el estado ha violentado el derecho a una vida libre de violencia.

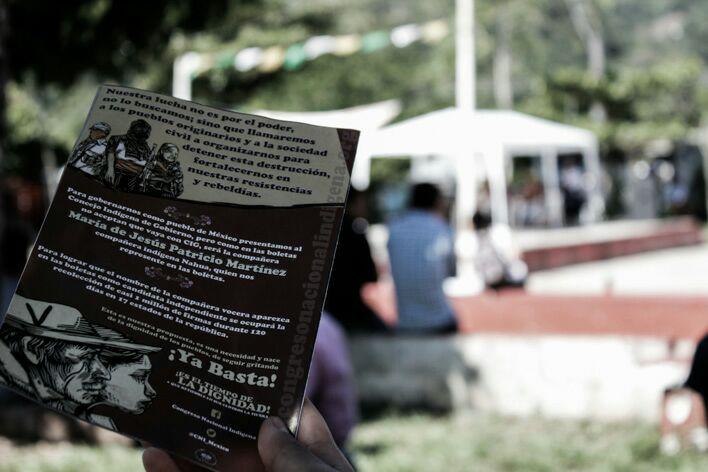

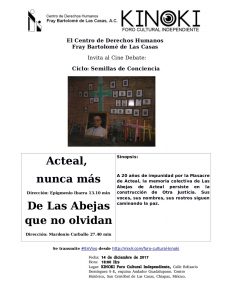

Las organizaciones civiles integrantes de esta misión, creemos que no hay voluntad clara de las autoridades mexicanas de resolver esta situación, la espiral de violencia es cada vez más grave y las condiciones están dadas para que ocurra un hecho de violencia más grave que nos recuerdan las condiciones que se daban en esa misma región hace 20 años antes de la masacre de Acteal.

Las decisiones erradas de la entonces Secretaria de la Reforma Agraria para resolver el problema limítrofe entre Chalchihuitán y Chenalhó que ha traído una tensión histórica entre ambos municipios, las acciones contrainsurgentes a través de la implementación del Plan de Campaña Chiapas ‘94 en la región, la liberación por parte de la Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación (SCJN) de los paramilitares responsables de la masacre de Acteal, la violencia histórica con la que operan los grupos civiles armados en Chenalhó, los conflictos generados por los partidos políticos, de manera específica por el Partido Verde Ecologista de México (PVEM) a través de la alcaldesa Rosa Pérez Pérez, con el cobijo del ahora gobernador Manuel Velasco Coello han traído una violencia cíclica, aumentando la impunidad que se vive en la región.

Las organizaciones integrantes de la misión de observación y documentación de derechos humanos y firmantes de este pronunciamiento hacemos un llamado a las autoridades de los tres niveles de gobierno:

Exigimos un alto al fuego, desarme y sanción a los grupos civiles armados en la región, así como una investigación a fondo de las autoridades responsables de la organización y actuación de los grupos armados.

Al gobernador Manuel Velasco Coello le exigimos asumir su responsabilidad como mandatario del estado y atender de manera integral y de fondo la espiral de violencia que existe en la región, las violaciones a derechos humanos y emergencia humanitaria en la que encuentran las y los desplazados de Chalchihuitán y Chenalhó.

Es importante que el estado mexicano reconozca la situación de emergencia y desplazamiento forzado de los habitantes de Chalchihuitán y Chenalhó, para su atención integral de acuerdo al marco legal y a la normativa internacional de derechos humanos.

Es urgente crear las condiciones que garanticen la vida y la integridad personal de las y los desplazados para que puedan retornar de manera de segura, como lo marcan los Principios Rectores de los Desplazamientos Internos en caso contrario el gobernador de Chiapas será responsable de la pérdida de vidas a consecuencia del desplazamiento.

Frente al riesgo inminente contra la vida, integridad o libertad de niñas, niños y adolescentes es importante la ejecución y coordinación de medidas urgentes de protección como lo marca la Ley General de Derechos de Niñas, Niños y Adolescentes y garantizar el derecho de prioridad en la atención a la infancia.

Pedimos a las autoridades municipales y tradicionales de Chalchihuitán y Chenalhó para que a través del diálogo y mediación puedan resolver el problema histórico de límites entre ambos municipios y que fue creado por las instituciones del gobierno.

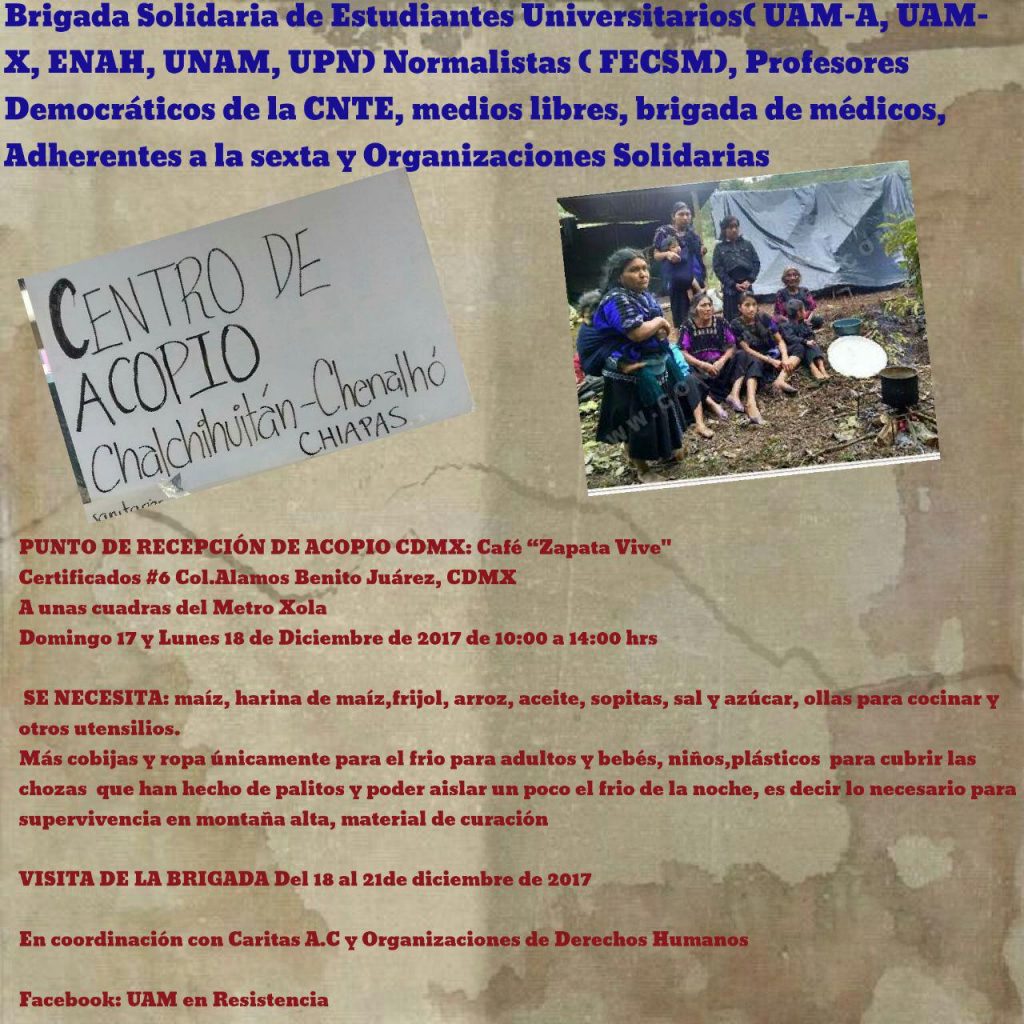

Ante la crisis humanitaria se hace necesaria la solidaridad internacional y nacional, debido a la ineficacia e incapacidad de atender esta situación de emergencia por parte de los gobiernos federal y estatal. Urge ayuda humanitaria para las comunidades desplazadas.

Campaña contra la Violencia Hacia las Mujeres y el Feminicidio en Chiapas

Centro de Derechos Humanos Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas A.C

Centro de Derechos de la Mujer de Chiapas, A.C

Servicios y Asesoría para la Paz A.C

Melel Xojobal A.C

Enviar su ayuda a Cáritas, Diócesis de San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Prolongación Benito Juárez #8, Planta Alta, Colonia Maestros de México, C.P. 29246 San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, México. Tel. 01 967 6786479. Celular de emergencia 967 1203722. caritas@caritasancristobal.org

Donativos económicos para emergencias

Cáritas de San Cristóbal de Las Casas A.C

BANCO MERCANTIL DEL NORTE

Cuenta: 0642624985

Clabe::072130006426249855

BIC/SWIFT: MENOMXMTS S.A.

San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, México

13 de diciembre de 2017

Pronunciamiento conjunto